Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionKökköz is an old Tatar village in the broad, beautiful valley inland from the dramatic Crimean Mountains. Between the annexation of 1783 and the Russian Revolution the it became the centre of one of the vast Russian estates established by Catherine the Great and her successors on lands either that once belonged to the Crimean khans or to Tatars who had fled the peninsula or been sent into exile.

Beyond the village, in what must have been a paradise of gardens and orchards, stands Crimea’s most romantic country house. It was built as a hunting lodge by the powerful Yusupov family, along with the stone mosque they gave to the village in 1910, a bridge and a handful of fountains.

Today the lodge seems to serve as a dormitory for inner-city children given the chance to breath the pure country air during the summer holidays. The grounds seem abandoned. According to reports they used to be turned into a sort of Soviet Butlins. Nowadays no one seems to object when you arrive unannounced and out of season, nudge open the iron gates on the country lane leading past the mosque and set out to explore the melancholic park. The house has a deserted feel, but for kitchen noises emerging from the caretaker’s flat in the basement groundfloor.

The Cultural Heritage of Crimea, a downloadable listing of key sights in Crimea, gives a potted history of the house.

The Yusupovs, a powerful Russian noble family said to be richer even than the Romanovs, bought the village and surrounding estate in 1908, and the heiress Princess Zinaida Nikolaevna Yusupova commissioned Nikolay Krasnov to build her a country house. Krasnov – the prolific Yalta architect also responsible for the Yusupov Palace there (where Stalin stayed during the Yalta Conference) and for Nicholas II’s new Livadia Palace – took the Khan’s Palace at Bahçesary as his inspiration, hence the introduction of a shed roof over the veranda, ‘peaked chimneys, white walls and lancet windows’. The house took him two years to build. The estate included a new bridge across the river, ‘a mosque in front of it (a gift from the prince to the local people). Apparently there were four fountains. Two were inside the building. One in the drawing room was ‘a copy of the Fountain of Tears’. Another was known as ‘The Fairy Tale’ fountain. Inside the arched entrance, there was a ‘forged bronze lattice door’ to ‘let the night air to cool the house in summer’. A specially laid riverbed allowed them to divert the stream; it was stocked with trout for guests to fish. The park was divided into ‘several large meadows’ and adorned with ‘lakes, fruit trees, cypresses, vineyards and cypresses’.

In 1914 Princess Zinaida Nikolaevna Yusupova gave the house and the estate to her new daughter-in-law Princess Irina Alexandrovna, wife of the young Felix Yusupov. Princess Irina’s uncle Nicholas II was among the visitors along with King Manuel of Portugal. Everyone who visited was impressed by the beauty of the building and the views.

During the Great Patriotic War (the Second World War), the house was used by officers of the occupying German army. It has since been variously a holiday camp, a club, a museum and a boarding school. As the authors of the guide delicately put it, ‘Time and multiple “owners” did not spare the magnificent park and interior of the house’. The furniture was removed to the museum of the Khan’s Palace in Bahçesaray for safekeeping.

The Yusupovs were an extraordinary family: one of the wealthiest in Russia, with a huge palace in St Petersburg. They were actually of ancient Tatar stock, claiming descent from Timur’s master strategist. Ever the strategists, they wisely converted to Orthodox christianity in the 16th century. Things went horribly wrong for the last Prince Felix, whose wife was given the hunting lodge at Kökköz. He became involved in the plot, eventually successful, to murder Rasputin, and was exiled for his pains to Crimea. After the Revolution, he managed to get back some of the family jewels by returning to St Petersburg in the disguise of a woman.

Another of Kökköz’s attractions is its famous walnut jam, sold from roadside stands by friendly Tatar and Russian villagers, along with a hoard of other forest fruit preserves. Even if the large jars are impossible to carry on a plane these days, it makes a very good breakfast treat, and an excellent present for hospitable Crimeans you might meet along the way.

The editor welcomes travel tips from Cornucopia subscribers. Please email feedback@cornucopia.net.

Only 20 years after Mehmed the Conqueror captured Istanbul, Crimea became an important, but autonomous, part of his burgeoning Ottoman Empire. After 1475 the Crimean khans, descendants of Genghis Khan, increasingly came under Ottoman sway. They started building their capital and palace at Bahçesaray (literally Garden Palace) around 1530, and went on adding pavilions and baths, courtyards and gardens for 250 years. The town turned into a miniature Ottoman city, their palace into a miniature Topkapı.

Bahçesaray’s small size belies its significance. The palace is a unique gem – the only one of Ottoman design to survive outside Istanbul. And Crimean Tatars have exerted a strong influence on Turkey, first as mounted archers vital to the expanding empire, and more recently as prominent figures in the arts, educational reform and Ottoman historical research.

Not much is left of the town Bossoli painted here, but the Turkish connection – and the Tatars’ Turkic language – have survived Catherine the Great’s annexation, Stalin’s Terror and exile of the Tatars, and recent upheavals in Ukraine and Russia.

Bossoli shows the palace as a harmonious assembly of low buildings round a spacious courtyard. On the left, walled gardens lead from the octagonal Falcon Tower to the pavilions of the harem and the audience hall. On the right are the minarets of the great Friday mosque and the monumental tombs of the rulers.

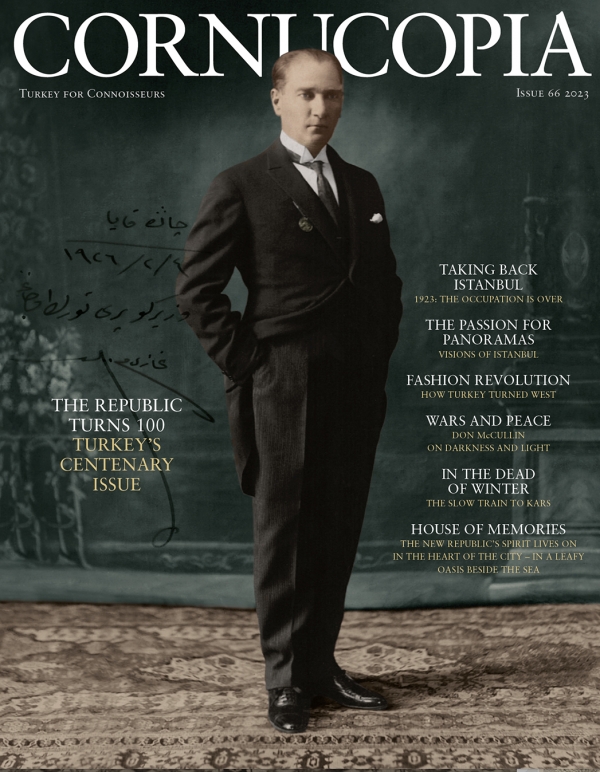

Issue 66, December 2023

Turkey’s Centenary Issue

Issue 66, December 2023

Turkey’s Centenary Issue

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now