Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital Edition

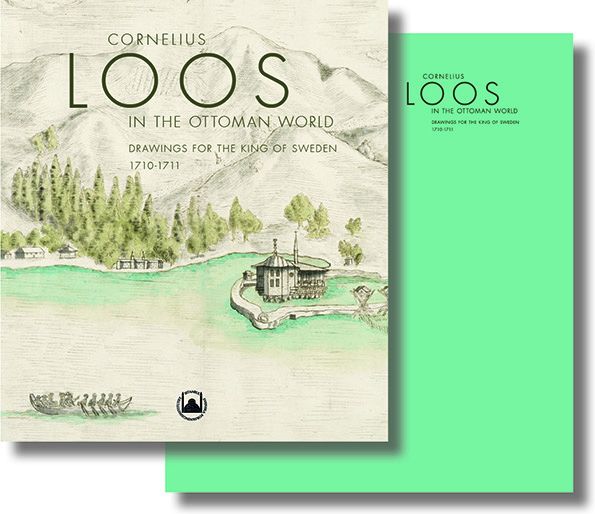

Drawings for the King of Sweden (1710-1711)

Following his defeat to Russia at the Battle of Poltava in 1709, the Swedish king Charles XII fled to the Ottoman Empire and took up a temporary residence in Bender, in today’s Moldova. From here, he dispatched three of his young officers on a journey from Constantinople to Cairo with the mission to make drawings of various sites, cities and monuments in the Ottoman Empire. One of them, Cornelius Loos, returned to the king’s camp with more than 250 drawings, most of which were lost in the so-called kalabalık in 1713. Fifty of them survived, having been kept under the king’s own bed.

Loos’ drawings are unique documents of Constantinople in the early 18th century, featuring vast, detailed panoramas, a large map of the city, and interiors of important buildings like the Hagia Sophia. They are accompanied by minor drawings of various sites throughout the Ottoman Empire, from the Black sea to the Pyramids in Gizeh.

The Loos collection, today kept in the National Museum in Stockholm, is here presented in its entirety for the first time, in illustrations and facsimiles, and in texts outlining their historical context and importance. The box set includes two magnificent facsimile panoramas 4 metres wide and Loos’s map.

The book was designed by Ersu Pekin and featured in two articles, by Philip Mansel and Robert Ousterhout, in Cornucopia 63. Subscribers can read them online here

One of the Ottoman sultan’s many grandiose titles, Refuge of the Universe (Âlem-penah), was no empty boast. Thousands of foreigners took refuge in the Ottoman Empire, from Spanish Jews fleeing the Inquisition in the 15th century to Greeks spurning national independence in the 19th. The most famous was the warrior king Charles XII of Sweden, of whom Samuel Johnson would write: He left the name, at which the world grew pale, To point a moral, or adorn a tale.

After the king’s defeat by Peter the Great at Poltava in what is now Ukraine in July 1709, he arrived on Ottoman soil with around 1,000 Swedish soldiers. The Ottoman Empire had been a Swedish ally since the 1650s, and it was nearer, and safer from Russian attacks, than Poland.

For five years Charles XII ruled Sweden from the small town of Bender on the Dniester, in what is now Moldova. The Council of State in Sweden was perhaps relieved to keep the unpredictable soldier-king at a distance. Such disregard for distance confirms not only the central role of the Ottoman Empire in European politics, but also the adaptability of 18th-century governments, and the energy of their couriers. Sweden functioned with a head of state living 1,500 miles from the capital; the Ottoman Empire sheltered (and subsidised) a foreign, Christian monarch and his troops.

At first the King lived in a tent in a camp called, after himself, Karlopolis; some of his followers lived underground in what they described as “rabbit holes”. Religious services, military drill, riding and music – JS Bach’s brother entertained the king on the flute – occupied part of the time. Research was another activity. Charles XII, who was studious as well as bellicose, sent three expeditions round the Ottoman Empire. Two were led by Michael Eneman and Erik Benzelius, preachers keen to expand their religious knowledge. Benzelius returned with one of the first known paintings of Mecca, now in Uppsala University Library.

The principal expedition, and the subject of Cornelius Loos in the Ottoman World: Drawings for the King of Sweden, 1710–1711, a magnificent book edited by Karin Ådahl, was led by three officers in their 20s, Cornelius Loos, Conrad Sparre and Hans Gyllenskiepp. They left Bender in January 1710 and returned 18 months later – on June 28, 1711 – having avoided plague and bandits and seen Cairo (six weeks), Jerusalem, Baalbek and Aleppo. In Loos’s words, he “put very humbly my faithful relation of my very fatiguing and very perilous travels at the feet of His Majesty, who received it very graciously and was very satisfied with it, after He regarded the various drawings, models, the very ancient paintings, idols of gold and silver, of coral, of stone and clay, the eternal lamps [sic], the great quantity of ancient medals”. Loos also brought engraved stones, a mummy, a petrified child, plants, hieroglyphs and drawings. The subjects of Loos’s drawings include three panoramas of Constantinople, hamams, the Bosphorus, the Ottoman fleet, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, and the Pyramids. Eleven detailed drawings of Ayasofya and the tomb of Süleyman the Magnificent confirm that foreigners could enter Ottoman mosques.

Unfortunately, many drawings were burnt or lost in a riot, or “kalabalık”, staged by the local governor on February 1, 1713, to drive away Charles XII. Fifty drawings survive only because they were kept in a trunk under the King’s bed. Charles XII moved to outside Edirne, then to Dimetoka, in what is now Greece. He left Ottoman territory in late 1714 to continue fighting in Scandinavia, as did the three travellers. After Charles XII’s death on November 30, 1718, the alliance between Sweden and the Ottoman Empire continued, indissolubly linked by fear of Russia. It inspired another great work, the Tableau général de l’Empire othoman by the Swedish dragoman Mouradgea d’Ohsson, published in three volumes in 1787–1820 (see Cornucopia 62).

1. STANDARD

Standard, untracked shipping is available worldwide. However, for high-value or heavy shipments outside the UK and Turkey, we strongly recommend option 2 or 3.

2. TRACKED SHIPPING

You can choose this option when ordering online.

3. EXPRESS SHIPPING

Contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net for a quote.

You can also order directly through subscriptions@cornucopia.net if you are worried about shipping times. We can issue a secure online invoice payable by debit or credit card for your order.

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now