Buy or gift a digital subscription and get access to the complete digital archive of every issue for just £18.99 / $23.99 / €21.99 a year.

Buy/gift a digital subscription Login to the Digital Edition

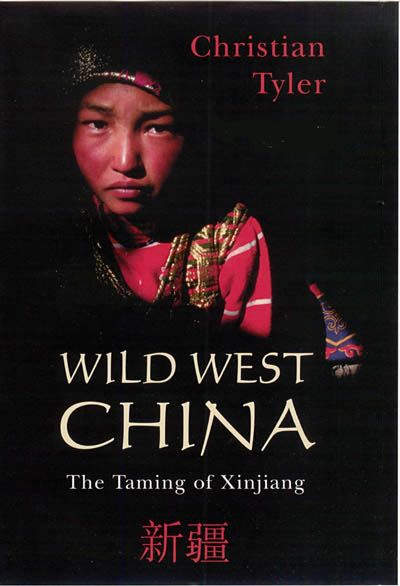

The Taming of Xinjiang

There are a lot of skeletons in the sands of Xinjiang. Archaeologists have discovered prehistoric mummies with perfectly preserved bodies, and the wind is now blowing the sand off the bodies of recently executed political prisoners. Christian Tyler has walked across the Taklamakan Desert and has seen these emerging corpses with his own eyes.

The proof copy of this book came in two halves. Since there is something to be said for reading history in reverse, I started with the second volume. Surprisingly, it opened in old Istanbul, in the courtyard of the Damat Ibrahim Pasha mosque, where Tyler met ‘the General’, Mehmet Rıza Bekin. A veteran of the Korean War and once assistant chief of staff at cento (a pact that includes Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, the UK and the USA), ‘the General’ was born in Khotan in 1925 and left Xinjiang with his uncle, the Emir of Khotan, when he was nine. The family escaped across the Kunlun Mountains into Ladakh, finishing up in Afghanistan, where they stayed for a while before settling in Turkey. The old general has taken on the role of figurehead of the exiled Uighur people of Xinjiang, whose plight he says he can no longer ignore.

Tyler, who used to write for the Financial Times, has taken up the story of the Uighurs and the exploitation of their land by the Chinese with the controlled passion of an academic journalist. The Chinese, when pressed by human rights organisations, are now able to invoke the international war against terrorism to justify their treatment of the Uighurs. Their view is that Xinjiang has been part of China since 60BC. Tyler points out that it is more accurate to see Xinjiang as an occupied country undergoing its sixth or seventh invasion in two millennia. His account of the suffocation of this ancient people and their culture is gripping and frightening. To understand the background, I started the book at the beginning.

The southern part of Xinjiang is a string of oasis towns around the once impenetrable Taklamakan Desert. Behind the towns is a ring of mountain ranges: the Kunlun backing onto Tibet, the Karakorams, the Pamirs and the Tien Shan backing onto old Russia. To the north of a spur of the Tien Shan is Jungaria, the northern part of Xinjiang extending up to Mongolia. Well into the twentieth century Urumchi, the northern capital, was fifty days’ journey from Kashgar, the second city. It is indeed the Far West.

The legend of the lovely Ipar Han shows the Chinese and Uighur views of each other. Captured from Kashgar in the eighteenth century by the Manchu emperor Qianlong, she was taken back to Beijing. Along the way her body was washed in camel’s milk and polished with butter. Kept in a gilded palace, with a miniature oasis, a garden full of singing birds, a mosque and a Muslim bazaar to amuse her, she pined away. She asked for an oleaster tree to cure her homesickness. This the emperor brought for her and she became reconciled to her lot. According to the Chinese, she lived happily ever after and still represents the taming of the newly acquired lands of the exotic west.

The Uighur version of the story has her pacing her gilded cage with daggers up her sleeve to repel the emperor’s advances until his mother, the dowager empress, forces her to accept the privilege of death. Hers is the story of the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, a region which has no autonomy and no longer belongs to the Uighurs.

Tyler takes us through the early history of the region: the ancient Uighur kingdom, the Tang empire, the Mongol invasion, the Manchu conquest, the period of Uighur independence in the nineteenth century, the Chinese reconquest and the subsequent revolts and their suppression. In 1877 the Chinese, with a loan from the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, defeated the legendary Yakub Bey and embarked on populating Xinjiang, which means New Frontier, with Chinese settlers and Chinese administrators. The Uighurs were easily pacified, but there followed an intermittent series of revolts by Muslim Chinese from the north.

Communist rule changed everything. In 1955 it created the Autonomous Region, adopting the old Chinese practice of yiyi zhiyi (using the barbarian to control the barbarian). Uighur party stooges were appointed as people’s delegates, while behind every senior – and powerless – Uighur cadre sat a Chinese official who answered to Beijing. Forced collectivisation saw an exodus of the herdsmen with their flocks to Afghanistan or Kazakhstan. The Great Leap Forward and the consequent famine of 1959 saw a westward migration of Chinese to cultivate the marginal lands of Xinjiang, which naturally caused a shortage of water and degradation of the pastureland. The Cultural Revolution of 1966 saw Chinese intellectuals and other undesirables banished to the vast laogai (gulag) work camps of the far west – and the trains are still daily hauling them in. The Uighur became a minority in their own land and suffered much discrimination.

For a period after Mao’s death they were better treated, but 1989 and the Tiananmen affair led to the beginning of a decade of violent confrontation with the state. The government, with its long memory of insurrection in the borderlands, dealt firmly with the ‘splittists’. Muslim civil servants, teachers and students were watched during Ramadan to make sure that they ate, mosques were demolished and books on Uighur history were suppressed. All the good jobs were given to Chinese immigrants. Educated Uighurs left the country to seek their fortunes elsewhere. A few of those that remained demonstrated and there were calls for a jihad, with the inevitable reprisals. Tyler documents these incidents in impressive and chilling detail.

While the Chinese authorities attribute these disturbances to foreign plots, whether from Turkey or the Taliban, Tyler’s impeccably researched and fully annotated book makes the point, first made by the British consul in Urumchi in 1945, that “there are ample causes purely internal to Xinjiang to explain events”. ‘Terrorism’ cannot be fought by fighting it.

1. STANDARD

Standard, untracked shipping is available worldwide. However, for high-value or heavy shipments outside the UK and Turkey, we strongly recommend option 2 or 3.

2. TRACKED SHIPPING

You can choose this option when ordering online.

3. EXPRESS SHIPPING

Contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net for a quote.

You can also order directly through subscriptions@cornucopia.net if you are worried about shipping times. We can issue a secure online invoice payable by debit or credit card for your order.

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $23.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now