Buy or gift a digital subscription and get access to the complete digital archive of every issue for just £18.99 / $23.99 / €21.99 a year.

Buy/gift a digital subscription Login to the Digital EditionThe magnificently detailed 19th-century engraved maps of Crimea published in German, French and English on display in the new La Richesse museum of Crimean Tatar history near Bakhchisaray are evidence that Europeans were more familiar with Crimea in the nineteenth century than they were in the twentieth. The Crimean War is the obvious explanation, and this was said to be where modern war journalism, with its telegraph dispatches and photography, was born. For most of the twentieth century Crimea, along with the rest of the Soviet Union, was effectively inaccessible and became a hazy notion for many. Today, however, it is back on the map and being rediscovered by travellers – and by its longest-standing indigenous occupants, the Crimean Tatars.

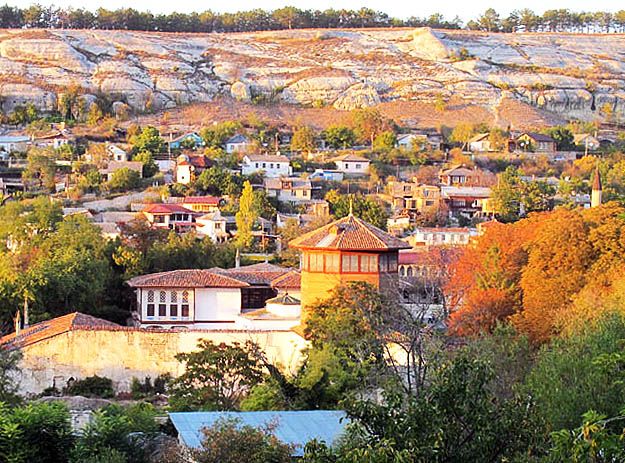

A special report for cornucopia.net by Robin Thomson

A bright diamond of a peninsula into the Black Sea from its northern coast, Crimea (qırım – ‘my hill’, originally the name of a town in its east, now Eski Qırım) has been the strategic goal of a dozen peoples through history, among them the Khazars, the Karaite Jews and a strand of the Golden Horde by Batu Khan that became the Crimean Khanate. Speaking a Turkic language (much of it recognisable in modern Turkish with a few spelling shifts), the Crimean Tatars went on to be allies of the Ottomans. Tensions arose with the arrival of the Russians in the region, though men of vision like Ismail Gaspıralı did much to build links between the Muslim world and the Russian Empire. Most of the Crimean Tatars were deported by Stalin; today Crimea is a part of Ukraine but has the status of an autonomous republic, in which a cultural revival is under way.

Today Crimea carries records of both the Crimean Tatars and the Russians; dig deeper and you’ll find others too. In Bakhchisaray a Jewish graveyard lies close to a Russian Orthodox monastery in a cliff above the Zincirli medrese, one of Crimea’s most respected Islamic schools (recently restored with funding from Turkey), and in the abandoned hill-top cities the ruins of mosques stand across the street from Jewish places of gathering.

Geographically, the north of the peninsula is flat dry steppe and little visited by travellers, while from Simferopol southwards it rises to a plateau and then splits into dramatic canyons that form the backdrop to many of Crimea’s sights. In the far south rise the jagged Crimean mountains, whose southern flanks drop sharply to the sea in some places. Inland are a number of ruined cities on clifftops, spectacular hikes in themselves and bearing the traces of a diversity of peoples.

Crimea is an autonomous region within Ukraine, and as such the official language – such as you will see on all public signs – is Ukrainian. Historically, however, 20th-century Crimea was Russian and today it is still more common to speak Russian, particularly in the holiday and coastal areas. Sevastopol is in fact still being leased to Russia as its main warm-water naval port. Go into the villages and there is a good chance you will encounter Crimean Tatar. This has much in common with Turkish and Turkish speakers will have no great difficulties.

There are various Russian phrasebooks available with basic phrases for travellers. Online examples include What is Russia or Russian Phrasebook. Ukrainian may look similar to the uninitiated but has significant differences of spelling and sound and is much closer to Polish. A useful start is at Omniglot.com or Wikitravel.

Turkish Airlines has daily flights from Istanbul to Simferpol (arriving early morning and departing late evening). Flights also arrive from Kiev and from there you can fly to Simferopol or take an overnight train. Simferopol is the Crimean terminus for many trains from the Ukrainian and Russian network, with summer holidaymaker trains laid on even from far corners of Siberia taking several days to reach the sunny peninsula. In summer a train runs from Berlin. South of Simferopol there is only one line, to Sevastopol via Bakhchisaray. Within Crimea railways are thus of limited use, and in any case require a basic command of Russian. The odd ferry sails to Sevastopol from Istanbul but timing and information are erratic. A better service runs to Odesa, from which a night train links to Simferopol.

Most other destinations within Crimea are reached by buses, from several bus stations in Simferopol; note that these are invariably full and it may be necessary to buy a ticket and wait an hour or two for a seat. Minibuses are more informal, more frequent, even more packed and driving standards are variable. Trolleybus route 52 is the longest in the world, running 54 miles from Simferopol via Alushta to Yalta, arguably the most relaxing mode of transport if a little slow. Alternatively, hire a car and driver. At Simferopol railway station, you can join with other passengers to share the cost. When preparing its special Crimean issue, no 49, due out April 2013, Cornucopia travelled with the excellent Taxi “Express” (+38 050 808 6972) – for an 8-hour day their price is 1200 UAH (£100); for 24 hours it is 1550 UAH (£125).

Crimea is generally bundled with travel information on Ukraine, meaning it gets shorter shrift than it deserves. Highly recommended comes the Bradt travel guide to Ukraine by Andrew Evans. Sketchier but useful is the Lonely Planet guide. A good source – though not the only one – of rail tickets and general advice aimed at English-speakers is Real Russia, based in London, www.realrussia.co.uk.

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $23.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now