Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionA hole in the wall opposite the Süleymaniye Mosque serving steaming plates of perfectly-cooked beans.

Berrin Torolsan pays homage to this trusty staple of Turkish cuisine in ‘Bean Vivant’ in Cornucopia 50.

Even after so many years I can still recall the smell on the first day of school after the summer holidays: a distinct combination of ink from newly printed textbooks,the freshly cut paper of our notebooks, the woody scent of sharpened pencils. An equally vivid olfactory memory from the time is of the aroma of cooking beans wafting from our boarding-school kitchen. Beans with rice pilav was everyone’s highlight in the otherwise meagre repertoire of school food.

In the city or the countryside, in schools, barracks and homes, beans are a Turkish staple enjoyed by all. It is the same everywhere: beans, tasty and nutritious, play a key role in feeding the world.

The most widely consumed and cultivated is Phaseolus vulgaris, the common bean (also called the haricot, garden or French bean), of which there are numerous varieties, differing in colour, shade, texture and flavour, with two distinct forms: climbing “pole” plants and “dwarf” bush plants.

Beans grow fast, produce plenty of fruit, and bear yet more when picked regularly. The tender young pods are cooked as vegetables. Later, the pods are discarded and the mature seeds are dried and preserved. While fresh beans are the pride and joy of weekly markets from spring to autumn, in winter, the dried bean is the prima donna of the legume world.

Beans are the only member of the large Fabaceae family to have come from the New World. All other legumes – chickpeas, peas, lentils, fava or broad beans, and so on – travelled from the Old World to the New after the Spanish conquest. Columbus first encountered our common bean in Cuba, recording in his ship’s logbook on November 4, 1492, “faxones and fabas different from ours”. Modern research confirms that beans had been domesticated from very early times and, like potatoes and corn, were already a staple crop from the tropics of Mexico to the high Andes, where wild varieties are still found.

Cataloguing the plants in the royal gardens of Madrid a century later, the royal gardener to Philip II, a priest named Gregorio de los Ríos, clearly identifies tobacco, sunflower and beans as American imports in his book of 1592, Agricultura de Jardines. His fellow botanists were clearly confused, however.

In 1543 the German physician Leonhart Fuchs – whose name lives on in the lovely garden plant fuchsia, with its drooping magenta blooms – published a monumental herbal with woodcuts, the Kräuterbuch, in which he listed Gartenbohne (Pvulgaris) as originating in eastern countries.

Likewise, in Italy and France the common bean became known as Phaselus turcicus or fasiol de Turquie. Three centuries later, in 1884, the Swiss botanist Alphonse Pyramus de Candolle noted that “16th-century gardeners often called the species the Turkish bean”, and suggested it “came originally from Western Asia”. But if the bean, fasulye in modern Turkish, is clearly an American import, why was it believed in Europe, even by scholars, to be Turkish?

Professor Bert Fragner of Bamberg University in Bavaria comes to our aid, explaining how politics influences tradition and fashion in nutrition and cooking. The political axis of Madrid and Constantinople, two superpowers that were partners as well as rivals, had an enormous influence on the political climate shaping the economy and cuisine in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Commodities unknown to the Old World – tomatoes, paprika, corn and beans, not to mention the bird the English-speaking world knows as turkey – quickly found their way from the New World to Spain and onwards, via the North African coast and Egypt, to the Muslim enemy’s capital, Constantinople. From there they spread all over the Ottoman territories, across the Balkans, Anatolia and into the Fertile Crescent, decades before Italy, France and the rest of Europe were introduced to these exotic goods. Mediterranean cuisine owes its surprisingly uniform use of American imports to this Spanish–Ottoman hegemony.

The Bulgarian-born food historian Maria Kaneva-Johnson notes that the earliest mention of “the stranger from across the Atlantic” is in a Turkish document at the beginning of the 16th century. She also quotes references to pole and dwarf beans in Ottoman tax records for vegetables sent to market in the provinces (pashaluks). By the 1550s beans were so well established in Turkey that the traveller Hans Dernschwam was pleased to note that “lentils and faseole don’t cost much money”. The fact that he uses the Turkish name suggests he was seeing the common bean for the first time.

Also worth remembering is the role of itinerant gardeners in introducing new crops to neighbouring countries. For 400 years these Ottoman market gardeners roamed freely, building seasonal gardens along the Empire’s borders and even beyond, on the outskirts of European cities.

Professor Fragner concludes that by 1600 Ottoman cookery was the most advanced, fashionable and creative cuisine in Europe and the Mediterranean. Its influence can be traced as far as England. In 1699, at the age of 79, John Evelyn, best known for his diaries, wrote a book on salads, Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets, which includes a recipe for a pickle of fresh green beans in brine and vinegar. The botanist Philip Miller suggests how to cook these beans, which he grew at the Chelsea Physic Gardens, where he was chief gardener for 50 years from 1722.

Green beans are very much part of the summer culinary repertoire in Turkey, cooked in olive oil, pickled, or stewed with meat. Tons are produced annually to be eaten in their tender pods. Mile upon mile of beans can be seen from the Caucasus to the Mediterranean, sometimes planted with corn, which the bean plants happily climb, as in the ancient agriculture of indigenous Americans.

The common green bean known as ayşe kadın – named after a long-forgotten lady of that name – is so prized and so popular in Turkey that it has almost become generic. Whoever Ayşe Kadın was, her hybrid lives on, unstringy and full of flavour. Turkish housewives taking their pick at market stalls have a habit of snapping the pods between their fingers to test for crispness and tenderness, though vendors will reprimand them, “Ladies, please prepare your beans at home!” The type known as boncuk (bead) ayşe has tiny bead-like seeds inside the pod, whereas şeker (sugar) ayşe, as its name implies, is almost sweet.

The distinctive long, thin, emerald-green string bean, çalı fasulye, makes an elegant Istanbul speciality. The single fibrous string that runs along both sides of the flat pod must be removed, then the bean is cut into thin strips and cooked with tomatoes in olive oil.

There are many delicious local varieties of the common bean, too, such as gelin (bride) beans from Izmir, or ferasetsiz (slow, or lazy) beans from Bursa.

Last but not least, there is barbunya, another pole bean, whose pod is a strong pink flecked with white while the seed is white splashed with red. It takes its name from a fish, the equally beautiful and delicious red mullet. In spring the pods may be cooked while still green, before the seeds develop. More commonly, barbunya beans are sold ripe, when the shells split to expose beautiful speckled seeds. In season these are cooked right away or frozen; the surplus is left to dry and stored for winter.

Another winter staple is the dried white kidney bean, which grows on low, bushy plants, often without props, and is dried when the seeds are mature. The most common is the cylindrical horoz fasulye (literally cockerel bean). But the most sought-after is the large, flat dermason, first cultivated in a remote village of that name near Niğde, in central Anatolia, and originally reserved for the palace. Today the term dermason is used for large white beans grown anywhere, but they are still pricey. Erzincan in eastern Turkey is said to produce the best.

In the nearby province of Erzurum, the small, roundish, ivory şeker beans from İşpir, high above the Black Sea, are unrivalled in taste. Fahri Hüsrev, owner of a legendary roadside restaurant in Çayeli, near the port of Rize, owed his fame to this special variety. Happily, his children have opened branches in more accessible Istanbul and Ankara. It is chefs such as Hüsrev who have made a plate of beans and pilav a much-loved national dish.

Whether they are fresh and full of vitamins, or dried and packed with protein, fibre and complex carbohydrates, beans are little bombs of nutrition, and the perfect comfort food.

KIYMALI TAZE BARBUNYA

FRESH BARBUNYA BEAN STEW WITH MINCED BEEF

1kg fresh barbunya beans in their pods

2 tablespoons butter

1 large onion (chopped)

250g minced beef

1 large tomato (peeled and chopped)

Salt

1 small medium-hot chilli (optional)

Every country has its special beans that are sold fresh in summer and dried for winter. In Turkey, the most distinctive is barbunya, with its striking pink pod and mottled seeds, which are similar to Italy’s speckled borlotti beans. The pinto or cranberry bean will work very well, too. A chilli pepper will give this dish a hint of piquancy.

1 Shell and rinse the beans briefly.

2 Melt the butter in a pan and saute the onion. Add the mince and continue stirring until it is browned and crumbly.

3 Transfer the tomato and beans to the pan, along with the chilli if you are using it, and season with salt. Add a glass of watei; bring to the boil and cook, covered, over a gentle heat, stirring from time to time, and adding hot water if needed, until the beans are soft but retain their shape.

4 Serve hot with fresh bread and a bowl of refreshing green salad.

ZEYTİNYAĞLI AYŞE KADIN FASULYE

GREEN BEANS IN OLIVE OIL AND TOMATO SAUCE

500g fresh green beans

4 tablespoons olive oil

1 large onion (chopped finely)

1 large tomato (peeled and chopped)

Salt and sugar

This is a summer classic in Istanbul, where market stalls and greengrocers’ windows are piled high with succulent green beans. If the beans are fresh and tender, it doesn’t make much difference which variety you choose. Ayşe kadın are ideal, but any haricot bean is fine. Cooked this way they will taste delicious. Serving undercooked green beans as a side dish may be fashionable in international restaurants, but for this recipe beans should be simmered until the cooking juices reduce to a sauce and the beans are well done, which will enhance the flavour, transforming them from a mere side dish into a delicacy.

1 Top and tail the beans and string if necessary. Rinse and leave to drain.

2 Heat the olive oil in a pan, stir-fry the onion until translucent, add the tomato, and cook, stirring, a little more.

3 Transfer the beans to the pan and stir for another minute or two. Season with salt and sugar and add about half a glass of water. When bubbling, turn down the heat and simmer, covered, until the beans are tender and the juices have reduced.

4 Serve cold, as a starter or, more traditionally, after a hot main course.

For two pages of Berrin Torolsan’s eight classic bean recipes order Cornucopia 50

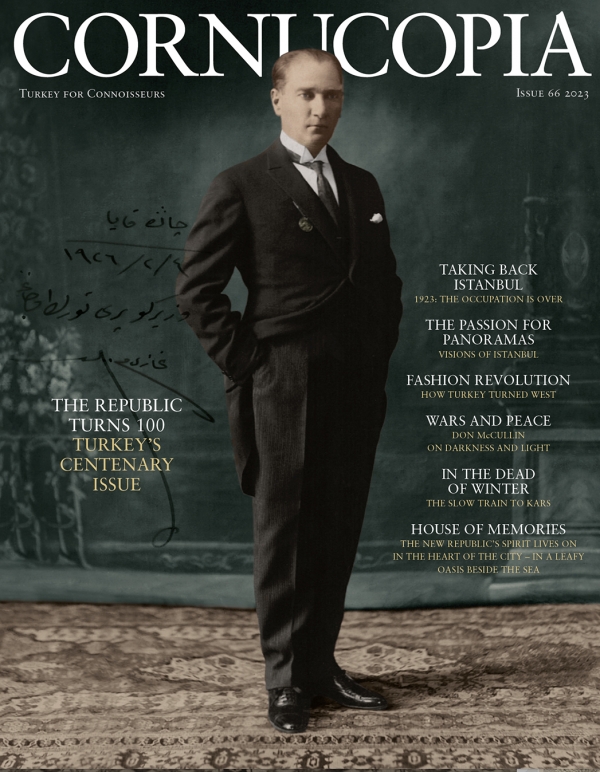

Issue 66, December 2023

Turkey’s Centenary Issue

Issue 66, December 2023

Turkey’s Centenary Issue

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now