Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionThe Bakewell Ottoman Garden, based on 16th-19th century Istanbul walled gardens, occupies a quarter acre of the Missouri Botanical Garden in St Louis. Edward L. Bakewell, a local property developer, died in 1993 and his sons chose this as a memorial, based on a family story that an ancestor had married an Ottoman sultan. The 79-acre Missouri Botanical Gardens are one of the oldest and most respected in the US, and they have a large orchid collection. The fact that they are on roughly the same parallel, 40 deg, as Istanbul means that Turkish native plants survive well here. The Ottoman Garden adds to the Japanese and Chinese gardens, while the Victorian District Garden surrounds Tower Grove House, built by the Missouri Botanical Gardens’ founder, Henry Shaw, a cutlery salesman from Sheffield

In May 1673 a French diplomat noted in his diary, after travelling from Edirne to Istanbul: “Had a wonderful time today. This was because of the fine weather and the large fields of tulips and peonies along the road to Burgaz.” Those bright blossoms in the fields were a harbinger of the famous Lâle Devri, the Tulip Era of the reign of Sultan Ahmed III (1703–30).

Antoine Galland’s diary entry is quoted (unfortunately without a reference) in the first of two books that appeared last year devoted to the history of tulips and tulip-fancying. Since Turkey and the Ottoman sultans’ enthusiasm for tulips feature quite prominently in both, Cornucopia readers may consider adding them to their collections of Turkey books.

The Tulip, by Anna Pavord, is a fat book with many fine colour plates. The author is a respected garden writer, with a column in a British weekly newspaper. Written with journalistic verve and almost febrile enthusiasm, her book attractively intertwines history, botany and horticulture. However, it is rather repetitive, and some will find 400 pages over-long, even for a flower as popular and widely grown as the tulip.

Tulipomania by Mike Dash is a pocket-sized hardback. He has a narrower focus than Pavord, who is interested in every aspect of the history of tulip growing. Dash concentrates on the Dutch and to a lesser extent the Turkish episodes of “tulipomania”.

Tulips are a beautiful bulbous plant. Their genetic make-up allows them to be bred in a huge range of colours and with strikingly patterned and shaped petals. Since the sixteenth century, Europeans have bred them intensively for their gardens and as cut flowers. It may be that in the tulip’s eastern homelands, enthusiasts were improving the wild species considerably earlier.

The two periods when it has become customary to speak of a mania for tulips were Holland in the 1640s and Istanbul under Ahmed III in the early eighteenth century. The craze for tulips under Ahmed III was nothing like as fevered as in Holland, and did not have the serious financial consequences. In Holland, as in France and England, tulips had been grown seriously since the sixteenth century, when the first bulbs were imported from the Ottoman empire, along with many other exciting plant species. Then, quite suddenly, thanks to the sophistication of the Dutch economy, the lure of large sums to be made from breeding showy tulips created a mad rush to speculate in tulips on the stock market. As Dash explains, vast sums were invested in the fanciest bulbs, which in three years led to a spectacular crash. The bursting of this first financial bubble dragged into bankruptcy not only tulip dealers and breeders but also many ordinary people.

In both cases, what particularly drove the tulip breeders and their clients wild was a curious fluke about this plant. Exquisite patterns can occur suddenly on a tulip’s petals, blotches, stripes and feathering, for all the world as if someone had taken a paintbrush to them. Thus one year, or for several years, a tulip has a yellow flower; suddenly, the next spring, it is yellow with red flashes. As Pavord tells us rather too often, the glory of the “broken” petals is caused by a virus carried by aphids, a discovery only made in the 1920s.

The strange tale of Dutch tulipomania is well known. As long ago as 1841 Charles Mackay brought tulips into his analysis of financial bubbles, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. Last year The Financial Times reprinted sections and, sure enough, there was the story of tulip fever. As I write, it is fashionable for financial journalists to ask rhetorically whether internet stocks are not a modern-day repeat of tulip mania.

The Dutch assiduously market their three-centuries-old love affair with tulips – small wonder given that every spring the brilliantly striped fields beside the grey North Sea prove a handsome earner from tourism as well as bulb exports.

That Turkey, or rather Istanbul, experienced its own phase of intense, if not actually manic, enthusiasm for tulip breeding is less widely known. The Istanbul tulip which Ahmed III’s court so appreciated was a distinctive strain – small, with a slender, waisted cup and petals with elongated points, sharp as daggers. After the fashion waned (quite when is unknown), the Istanbul tulip became extinct. Nobody has managed to breed its like again.

Pavord’s book is a better introduction to the Turks and tulips than Dash’s. His chapter, oddly entitled “At the court of the tulip king”, is based on a narrower reading of secondary sources and revels tiresomely in what one might call “Sultan smut”. So we read that Mahmud, Ahmed III’s successor, “asked nothing better than to hide behind a grill [sic] in the harem and spy on the women of the palace”. The comical misspelling makes it look as though barbecues were a regular feature of life for the odalisques. And what has the observation that Ibrahim the Mad deflowered a virgin every Friday got to do with flower-fancying in the horticultural sense?

There is ample evidence in Turkish literature, going back to the poets of medieval Central Asia, that Turks keenly appreciated wild tulips for their brilliant colours and because they herald the coming of spring. Almost all the many species of tulip were originally native to Central Asia, the Middle East and Asia Minor – a vast region, much of which was under Ottoman sway. Today, no fewer than fourteen species of tulip grow in the wild in Turkey.

Pavord describes looking for tulips one May around Van and Tortum (though her description of “ricocheting” along snowy roads sounds unlikely). She writes ecstatically about the scarlet blooms she and her companions find on the barren mountain slopes, and fellow tulip enthusiasts will envy her. I have never seen a tulip in the wild, and would dearly like to, especially the hot orange Tulipa sprengeri, probably the flower I treasure most in my garden, which is said to grow around Amasya. Incidentally, it is a pity that Pavord spells so many Turkish place-names incorrectly; Hosap and Maras just will not do. Why is it that English publishers (and, for that matter, newspaper editors) think it acceptable to disdain Turkish accent marks, but not accents in French or German?

Like many people, my experience of tulips in Turkey is limited to their image in art, although it is delightfully evocative when one finds the flowerbeds beside the mosque of Sultan Ahmed planted up with tulips. However, many of us feel as if the Istanbul tulip still lives on. Its flaring dagger petals feature ubiquitously in Ottoman art from the sixteenth century to today’s revivalist ceramics, but most of all in the art of the Tulip Era. Carved stone, tiles, coloured glass, manuscripts, carpets and embroideries, all bear abundant witness to the charm and distinctive elegance of the Istanbul tulip.

Godfrey Goodwin, grandee of Turkish architectural history, called the Tulip Period of Ahmed III “the entr’acte between the dying classical and the coming baroque”. Perhaps the most familiar witness to the wonderfully decorative, strongly Frenchified taste of the time is the famous little dining room created for the Sultan in the selamlık of the Topkap› Saray. Once seen and never forgotten, this exquisite room is entirely covered with painted panels. Each one shows either a vase or a lattice-work basket filled with fruit or flowers, just as a gardener might have presented it to the sultan’s kitchens.

However, it should be noted that tulips are just one among many blooms in the baskets. To depict a court obsessively arguing over the merits of tulips is a distortion of a far more complex picture of the place that flower cultivation occupied in the taste of eighteenth-century Istanbul.

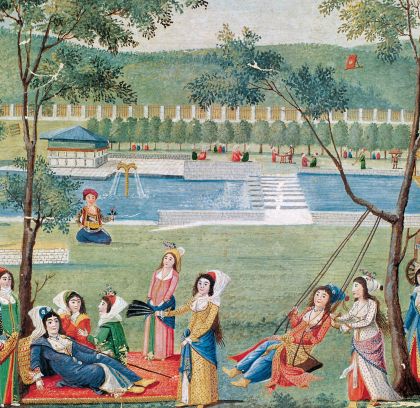

Anyone who lingers by the famous Sultan Ahmed fountain, rather than rushing straight on into the Topkap› Saray›, will see lovely panels carved in shallow relief with fruit trees in pots on presentation stands. Such elaborately carved and gaily painted fountains were one of the distinctive achievements of the period. Although the paint has long ago vanished, the fountains are a reminder of a typical feature of East and West at this time, the passion for outdoor enjoyment. The Turkish court held flower festivals in gardens along the Bosphorus which were beautified by little kiosks, pavilions and fountains – this at a time when European princes and nobles likewise revelled in expensive entertainments in their gardens.

Garden history is extremely popular in Britain nowadays, and increasingly in other European countries, too. In contrast, garden history enthusiasts are far less aware of the history of plants and gardening in Turkey. For this reason, it is rather a pity that the focus seems always to be on the so-called tulip mania. Those varied flowers in the Sultan’s diningroom tell another story, as does the French diplomat’s description of those fields of tulips and peonies. Turkish literature also testifies to the various flowering species which were held in deep affection: lilac, narcissus, hyacinth, rose and more. European gardens owe many lovely species to their having originally been imported from Turkey. It is perhaps time to leave the tulips alone, and to discover the wider background. We must hope for historians who know their archives and can bring alive Ottoman gardening in all its variety.

Back in March 2011, in what now seems an impossibly ambitious undertaking, I was camera-hunting rare irises on the Golan Heights and looking at gardens in Tel Aviv, Haifa and Jerusalem. It was the first research trip for a book I wanted to write on gardening in the Levant – from Alexandretta (modern-day Iskenderun) in southeast Turkey, to Alexandria in northern Egypt, taking in Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine. The epicentre of my proposed opus would be the Fertile Crescent, involving long stays in Syria over the next few years. Well, we know what happened there… and the project was necessarily abandoned.

I couldn’t, however, turn my back entirely on that part of the world, and regret was slowly overtaken by excitement and intrigue as I recalled a dawn glide down the Bosphorus in the autumn of 2008. Through binoculars from the deck of a small cruise ship returning from Ukraine (lecturing on gardens as part of the ship’s onboard cultural itinerary) I marvelled at numerous old houses and yalıs, shaded by cedars and pines of venerable splendour, suggesting the existence of secluded and perhaps little-known gardens.

Long-term commitments prevented any immediate return to Turkey but in the spring of 2012, as leaves on Istanbul’s plane trees slowly unfurled, I began the prospect of writing about its public parks and gardens, its threatened bostans (community vegetable gardens), hoping primarily to discover a cache of private horticultural havens struggling for supremacy in the concrete jungle or at verdant ease along the Bosphorus shores. While my focus is mainly post-Ottoman I cannot ignore gardens surviving from earlier times or, where hallowed trees still stand, cemeteries and mosques, setting my own boundaries north and south, from the Black Sea to the Princes Islands.

As a stranger, armed with little more than a Turkish dictionary, a map and a clutch of city guidebooks, I began my quest. Unlike the many countries where for more than a decade I have led specialist garden tours, Turkey could not provide a ready-made list of “must-see” gardens. I was starting from scratch in a city where, from a casual glance, any serious gardening seemed to have stopped abruptly a hundred years ago. Yet, so rich was that Ottoman heritage that I refused to believe I couldn’t find enough to satisfy my own Turkish garden cravings – let alone those of today’s many tourists thirsty for foliage and flowers.

With just two days left in Istanbul on that first extended trip, I went to Koç University to meet Scott Redford, who began to unlock doors on my behalf: most importantly that of Nihat Gökyiğit.

If, as an elderly Turkish gentleman sipping tea near Taksim Square told me, “a man can remember a woman with a single flower”, how much more romantic is it to recall her with a whole garden – more than 80 acres of it? Such is the gesture made by the businessman and philanthropist Nihat Gökyiğit in memory of his late wife, Nezahat, and you would be forgiven for thinking it the act of a bejewelled grandee from the Ottoman Empire’s glittering past.

But Nihat Bey is alive and as well as any man in his late eighties can be. On my last full day in the city we met at his office, which he frequents, though far beyond retirement age, as chairman of the board of Tefken Holding, Turkey’s largest firm of construction engineers. We became acquainted over toasted sandwiches and tea before setting off across the Bosphorus to the Nezahat Gökyiğit Botanic Garden (NGBG), a miracle of entrepreneurial horticulture under the directorship of Adil Güner, straddling – improbably – the intersection of two thundering motorways amid a forest of new apartment buildings and the recently completed Mimar Sinan Mosque at Ataşehir, some 20km from the city centre.

Among the NGBG’s glories are the tunnels that connect its various sections, each one an island, each devoted to different styles of gardening and different kinds of plants. One, perhaps 100 metres long, displays reproductions of pieces shown at the Istanbul 2010 European Capital of Culture exhibition. Subtly yet forcefully, each picture demonstrates Turkey’s universal exploitation of floral (especially tulip) and foliar imagery – from both realistic and stylised botanical illustration to landscape and miniature paintings, ceramics, clothes and shoes, soft furnishings, furniture, domestic and marine architecture, jewellery, clocks and tableware. All human needments are embodied, beyond life itself too, in the decoration of tombstones and, chillingly, such instruments of death as daggers, swords and gunstocks. The Ottomans were obsessed by plants and flowers and the skill of its artists and craftsmen was unrivalled. (Doubters might start with Orhan Pamuk’s My Name Is Red.)

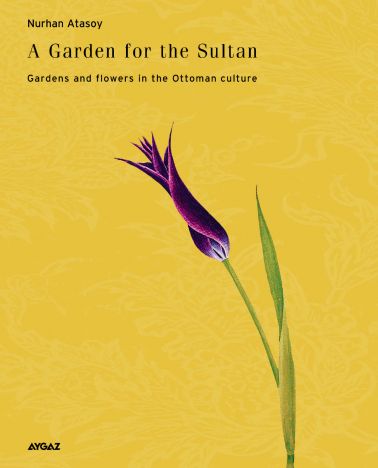

For an authoritative account of the Empire’s horticultural brilliance there’s Nurhan Atasoy’s A Garden for the Sultan (Kitapyayınevi, 2011), a book of great beauty and learning. Present-day Turkish designers are free from the confines of what Professor Atasoy describes as being “Ottoman” gardens seen partly in the Islamic mould. “In their westward migrations to seek land that was more fruitful than the arid steppes of Central Asia,” she says, “the Turks brought with them many of their ancient traditions” and, one might add, many plants from countries plundered en route. “Anatolia,” the professor explains, “is a land-bridge linking the flora of southern Europe on the one hand and that of southwest Asia on the other.”

Today’s Istanbul gardeners, in a climate sweetened by lapping water on three sides, can successfully grow a range of plants from two mighty continents, plus almost anything from their own catalogue of native flora, richer by far than any found in neighbouring states. Moreover, foreign travel, books and magazines are influencing a younger generation of garden designers, especially those hired by private clients (who may not be Turkish) or who seek merely to green-up an urban roof terrace.

Regrettably, an overcrowded Istanbul cannot provide new houses with large individual gardens, although in a meeting with Ihsan Şimşek, head of the city’s parks department, I was assured that current and proposed developments are being given recreational green spaces.

I have now made detailed notes about some of Istanbul’s better-known palace gardens (supremely Topkapı) and the city-owned Yıldız and Emirgan parks, where a vibrant style of municipal bedding-out appears to please the visiting hordes. Emirgan Park is lately revived by the conversion of old brick stables and carriage houses to accommodate the new Istanbul Lale Vakfı (Tulip Foundation): in its grounds the famous Tulip River is replanted each autumn with thousands of bulbs in advance of the citywide annual Tulip Festival.

I spent time at Istanbul University’s now sadly doomed 1930s Alfred Heilbronn Botanic Garden by the Süleymaniye Mosque, on a prized (and therefore super-valued) site overlooking the Golden Horn. Up in the Belgrade Forest, near Bahçeköy, a 45-minute Number 42 bus ride from Taksim Square, I combed the paths that delineate the species-rich Atatürk Arboretum in the company of the botanist Rahim Anşim. Within the book-lined walls of Nurhan Atasoy’s city-centre apartment I learned how today’s gardening is linked to the past, and from designer Gürsan Ergil, one of whose latest commissions is a garden for the new Turkish Embassy in Mongolia, I took the pulse of contemporary horticultural trends.

If those were some of my sunnier moments, then my darkest hour was spent on the Saturday afternoon of June 15 in Gezi Park. Threats to these few acres and their indispensable shade trees triggered the “riots” that much hampered my second summer visit this year. Yet, with the memory of teargas in my eyes I am eager to return, to trawl the city again, to peep behind locked gates and over high walls, to talk to gardeners young and old – all in search of Istanbul’s elusive parks and gardens.

The Turkish passiomn for flowers is well documented both by Turks themselves and by foreign visitors. It is remarkable that one of the few surviving portraits of Mehmed the Conqueror in the fifteenth century should have him sniffing a rose, which is hardly a belligerent gesture…

If the Turkish love of flowers inspired all Europe with a similar passion in the sixteenth century, it is as well to remember that many Turkish varieties came from further east, from Central Asia, and even China.

The debt north European gardens owe to Turkey is far greater than most gardeners realise. Botanists have long been fascinated by Turkey, with its unique mix of Mediterranean and Caicasian plants and spicing of influence from Central Asia. Turkish gradeners of today have a unique heritage waiting to be revived.

In the fifteenth century Mehmet the Conqueror made known his appreciation of flowers: a miniature in the Topkapı shows him sniffing a red rose, recognisable as the Red Damask, Rosa gallica ‘Officinalis’.

Issue 66, December 2023

Turkey’s Centenary Issue

Issue 66, December 2023

Turkey’s Centenary Issue

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now