Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionYolande Whittall looks back at 1930s life in Moda, across the strait from the domes and minarets of Istanbul. In Grandmother Whittall’s garden, where the snow fell deep and crisp, tobogganing parties were laid on for the children. In the kitchen Christmas puddings were stirred, and shooting parties provided the wherewithall for woodcock pie…

Great-grandfather first made Moda his home when he settled in Constantinople in 1873 and founded JW Whittall & Co. Thus it became home to our grandparents and our parents, and then to us, too.

He built a large stone house which overlooked the sea to the skyline of old Stamboul, pierced and scalloped by minaret and mosque dome. He travelled to and from his office in a rowing boat. Later he journeyed to England to be knighted by Queen Victoria.

Great-grandfather’s descendants joined the firm and built houses in Moda of stone or wood. As children we romped through their gardens, some of which tumbled down to the sea. Many foreign traders lived in Moda in those days, the largest foreign community probably being the British. They brought football to Turkey and built a church in Moda. They also introduced the Christmas tree.

One summertime treat was to be rowed in the dark under the cliffs to catch crabs among the rocks by dazzling them with a carbide lamp. There was rowing and sailing in Moda Bey and across the bay, and swimming from the sandy beach of Kalamış.

In a good year for snow, there would be tobogganing. My father was born on November 11, 1896 and small guests at his birthday parties would be entertained with toboggan races down the road that sloped to Moda Pier. Fortunately no one tobogganed into the sea.

On my father’s eighth birthday, my grandfather gave him a gun and, two months later, in January 1905, took him and his younger brother to Alemdağ. Here my grandfather had built a house which in winter was used as a shooting box. It was painted red and called the Red House. The 15-mile journey from Moda, in a covered talika in pouring rain, took six hours because of the mud, and they arrived after dark. Next morning they awoke to find the countryside white with snow and the water in the house frozen. It snowed all day and night, until it lay some two feet deep. The woodcock, meanwhile, had flown to the coast. Grandfather determined to follow them, walking to Domali, a village on the Black Sea shore – nor an exercise for novices.

Two straw-filled panniers were slung over a horse. A child was put in each, wrapped in the straw, and two villagers led the horse to Moda, where the boys were reunited with their mother. Grandfather returned later, laden with four roe deer, two wild boar, 30 woodcock, three pheasant and one duck. The bekçi, or nightwatchman, walked round the house, winter and summer, beating the hours on a stone with a big stick. Grandfather lent him a few gold pounds to buy land when he went to his village to dispose of the harvest. There he died. In the spring, a small boy dressed in peasant clothes came to the house. Grandfather asked him what he wanted. ” I have come to repay my father’s debt to you,” he replied proudly. “I have no money, but I can work.”

His name was Kamil. He worked as assistant gardener, then as assistant cook, and rose to the rank of butler, in a boiled shirt. He ended his career as a broker in the family business, having bought a house and married a town girl far above his village status.

There were parties with a Christmas tree at the Kadıköy Institute, and as the Orthodox Christmas came later, the choir from the Greek Church joined the British community in carol singing.

After the First World War, because the roads to Alemdağ had deteriorated, Grandfather hired a lonely house, deep in a valley behind the Çamlica Hills, three miles in land from the Bosphorus’s eastern shore. He named it Greenroads.

Here Grandmother loved to come, collecting mushrooms, gathering wild flowers and making arrangements of dried flowers for the winter. In the sitting-room and kitchen, in open fireplaces, great logs of oak and beech burnt day and night.

Turkeys from upcountry would be brought to Moda, and in the spring, as they gobbled and fluttered and strutted along the streets, Grandmother would rush out and bargain with the drover as she chose two or three for fattening for the following Christmas.

On March 1, 1929, and for several days after, ice floes from Romania and Russia choked the Bosphorus for the first time since 1862. A man walked across the Straits from Europe to Asia.

As children, we would be taken down to the kitchen where Kamil’s nephew, Osman, that most excellent of excellent cooks, would give us a large spoon and we stirred the Christmas pudding and made our wishes. Puddings were also made for people like the Miss Lynes, daughters of the first custodian of the Crimean Cemetery. After Christmas they returned not only the pudding bowls but also the paper and string in which they had been wrapped.

Grandmother’s family was spread around the world and she would have written her letters to them before breakfast. Osman would come upstairs in the early mornings to discuss, in Greek, the day’s work and meals. From a recipe of my grandmother’s, Osman made a woodcock pie, unparalleled in the world of game pies, to be served at Christmas lunch between the soup and the turkey, with a woodcock’s little head and long beak stuck at each end.

At the end of Mektep Sokak in Moda is a small bakkal, a grocer’s shop. It was run by Halim and Seher. He had been Sir James Whittall’s gardener and she had worked with the family as a maid. Halim had once been on a pilgrimage to Mecca. Eventually their nephew or adopted son took over and, with his wife and two daughters, lived above the shop. Once, in their tiny salon, they gave a luncheon party for members of the Whittall family still living in Moda. Today any of us on a visit is welcomed with hugs and kisses and invited in for tea or coffee. Seher was there to greet me this year, but Halim had died.

Today the only reminders of old Moda are the terebinth trees which hang forlornly over the cliffs, dwarfed and frowned upon by rows of flats which look down into their privacy.

Norman Stone introduces a special report by rescuers and writers on the August earthquake and its aftermath

War and Peace: Ottoman Relations in the 15th to 19th centuries’, an exhibition at the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, Istanbul, 1999 For 500 years the Polish elite was obsessed with all things Ottoman. Yet a brilliant exhibition celebrating this passion went sadly unnoticed. Philip Mansel reports.

Nine thousand years ago, the plain of Konya was a hive of activity. Before the Mesopotamians, Minoans or Egyptians, the people of Çatalhüyük created one of the first cities known to man. James Mellaart, who unearthed the city and its stunning wall paintings, recalls the stages of a momentous discovery

Soon after blue and white ceramic was born in China, it made its first glorious appearance in a mosque in the early Ottoman capital of Edirne. John Carswell unlocks a well-kept secret

A 20-page celebration of Safranbolu, the perfect small town. The lovingly maintained Mümtazlar Konağı is just one of the many handsome old houses that distinguish the Anatolian market town of Safranbolu. With iron deposits, lush forests and fields growing the valuable saffron croci that gave the town its name, Safranbolu prospered quietly for 1,500 years.

This modest plant grows easily, cooks easily and digests easily. It is also an excellent health giver. The 10th century physician Ibn-Sina (Avicenna) recommends leeks against colds, coughs and unclean air.

More cookery features

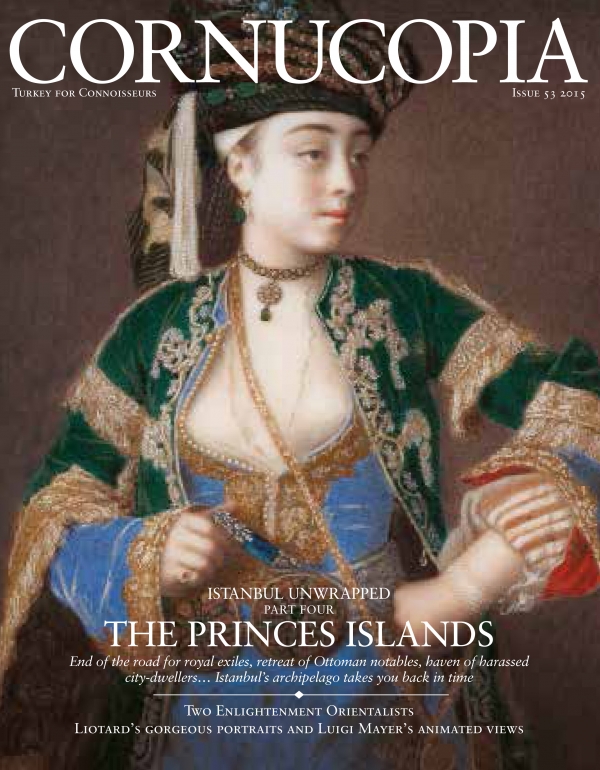

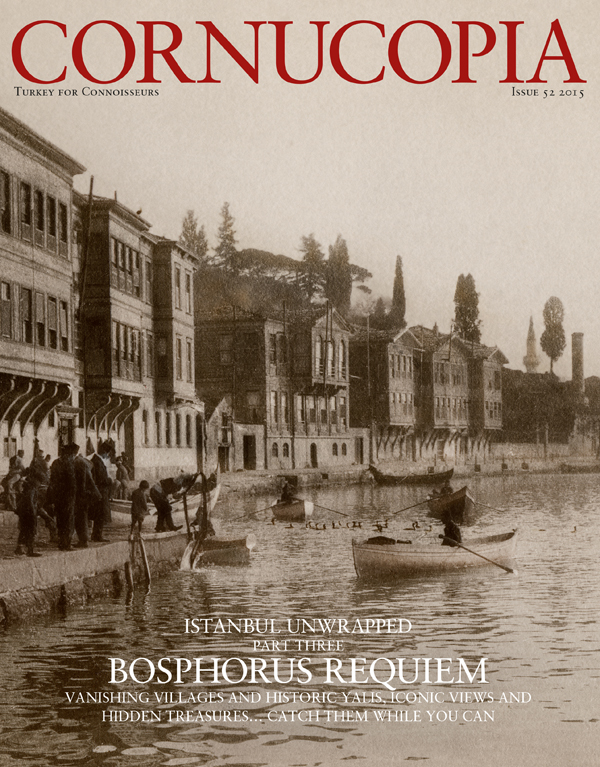

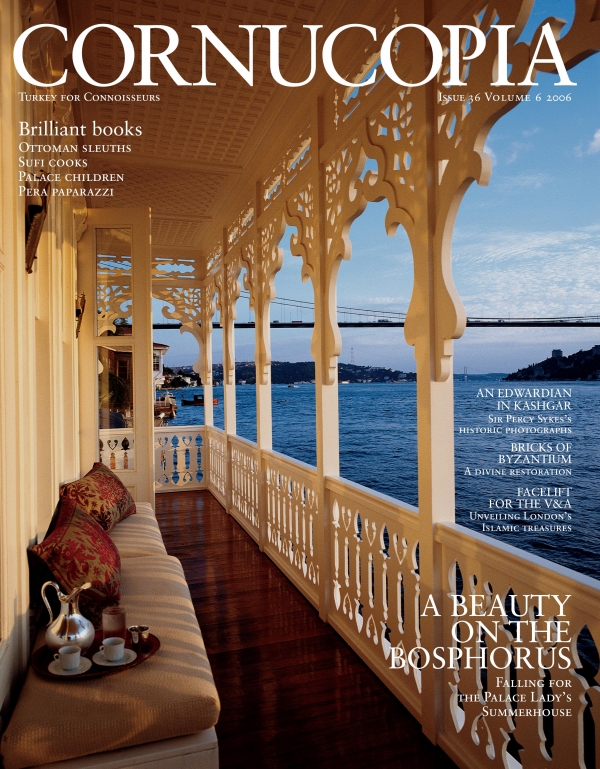

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now