Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionThe Pergamon Museum, built to house Germany’s acquisitions from the Ottoman Empire, remains one of the most jaw-dropping museum experiences in the world. Its highlights are the Pergamon Altar, the Miletus Market Gate and Babylon’s Ishtar Gate and processional way.

On an upper floor is the Museum of Islamic Art, recently the beneficiary of Edmund de Unger’s Kier Collection, and here the highlight is the façade of the 8th-century desert Umayyad Palace at Mshatta in Jordan. Excavated in 1840 and given as a gift by Abdulhamid II to Wilhelm II, it is 30 metres long and is carved with floral and animal figures. There is also a highly decorated reception room from a wealthy Aleppo merchant’s house, from around 1600.

The museum was built in 1901 and extended in 1930 specifically to house the Pergamon Altar. It had been excavated between 1878 and 1886 by a German engineer, Carl Humann, who had initially been involved in road building in Turkey. Granted permission by the Ottomans to take the altar away, Humann then oversaw its reconstruction by Italian craftsmen in Berlin. The altar dates from 180–160BC and is dedicated to Zeus and Athena, probably serving as a sacrificial altar at the entrance to the main temple. More than 35m wide it has two friezes. The one at the base depicting a battle between giants and gods is the largest surviving frieze from antiquity after the Parthenon’s, but it has two missing panels. These had been taken in 1625 by William Petty, an agent of the collector Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, and are now dispersed. One of them, depicting the torso of a fallen giant, was incorporated into a folly in Fawley Court, a country estate in Oxfordshire, the other, of the giant Porphyrion, is on display in the public library in Worksop, Nottinghamshire.

The site of Pergamon lies on two hills at 1,000 ft above the modern city of Bergama.

Equally theatrical is the 2nd-century AD Roman Market Gate from Miletus, a city founded by Aeolian Greeks on Turkey’s Aegean shore. Some 30 metres wide and 16 metres high, it was later incorporated into the city walls by Justinian, and was brought down in an earthquake in the 10th or 11th century. The site was excavated for four years by the German archaeologist Theodor Wiegand, who shipped 750 tons of fragments to Berlin. He undertook excavations at Didyma and Pergamon, and formed a flying unit under the Turkish military specifically to take photos of archaeological sights. Put in charge of the Berlin museum’s archaeology department, Wiegand was instrumental in setting up the Miletus Market Gate after showing a model of how its reconstruction might look to Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Writing in 1937, the theorist Walter Benjamin remarked that “The figure of the collector, more attractive the longer one observes it, has not been given its due attention so far. One would imagine no figure more tempting to the Romantic storytellers.

The type is motivated by dangerous though domesticated passions. Yet one searches in vain among the figurines of a Hoffmann, Quincey or Nerval for that of the collector.”

Perhaps no contemporary collector emblemised this more than the late Edmund de Unger – the Hungarian property developer who devoted his life to his Keir Collection of Islamic art. De Unger’s life took him from the old-world Hungarian high society of the inter-war period to Oxford in the 1930s, back to war-torn, then Communist, Hungary before he finally settled in London, where he began to collect Islamic art. In 2008 he loaned 112 items to Berlin’s Museum of Islamic Art for an exhibition that opened in March 2010. It was agreed that on his death the full collection of 1,500 objects would transfer to Berlin, to be housed in the Museum of Islamic Art, part of the Pergamon Museum complex.

De Unger was born in Budapest in 1918 into the haut monde of inter-war Central Europe. After the Great War, Hungary lost two-thirds of its territory in the Treaty of Trianon, but the Hungarian elite were determined to hold on to the fin de siècle they had enjoyed so much. The de Unger family were of old Budapest stock – counting among their ancestors the neoclassical architect Michael Pollak, designer of the Hungarian National Museum. Edmund’s father, Richard de Unger, a diplomat and patron of the arts, was also a friend of the famous German academic Wilhelm von Bode, the man behind many of the museums in Berlin today.

Like many of his class at the time, Richard de Unger was a passionate collector of Oriental rugs. Edmund often recalled first becoming aware of carpets when his father told him not to walk on the precious rugs that filled the house. The de Ungers’ wealth came from property: Budapest’s famous Hotel Astoria was part of their considerable portfolio. Thus, when Richard died in 1928, his 10-year-old son was left, as he would recall, with “a very large fortune in real estate, paintings and carpets”. His mother was also passionate about carpets and possessed a fantastic eye; after his father’s death she was keen to encourage her son. But the precocious Edmund far outshone his parents.

As a boy he had been taken by his father to the National Museum, where, unprompted, he accurately identified a painting by Jusepe de Ribera. At the age of 14, he stopped at a church during a Boy Scouts’ bicycle tour of Romania. Sizing up a damaged carpet – a section of which had been cut off to bandage a parishioner’s leg – he offered to buy the church a replacement in exchange. This rare 16th-century Turkish carpet, which in 1997 was on the floor of de Unger’s bedroom, was later valued at a cool $50,000.

With his unerring eye and head for business, de Unger continued to collect carpet fragments even after going up to Hertford College, Oxford, where his “not terribly intellectual” fellow students laughed at his “moth-eaten rugs”. The advent of war forced him to return to Budapest, where he managed his family’s business, trying to get as many heirlooms out of the country as possible. In a quiet show of bravery and integrity during the siege of Budapest, he sheltered 22 Jews in the family home. One, Eva Spicht, would become his wife in 1945. Following the war he restored the Hotel Astoria, later nationalised by the Communist government. Much of his collection was also lost, his father’s exquisite carpets being used by German and Russian soldiers to wrap the bodies of their war dead before burial.

In the early days of the Rákosi government, de Unger, like many of the Hungarian elite, was imprisoned three times before he was allowed to emigrate. “Tell me, Edmund,” an aunt asked on his release from a stint in jail, “whom did you meet this time you were in prison?” De Unger moved to London in 1948, and after working in Ghana for the Colonial Office, turned his business acumen to his family’s old profession of property management and their pastime of collecting.

The Keir Collection, named after Keir House in Wimbledon, where the de Ungers had a large flat, is undoubtedly one of the great post-war collections. De Unger began with carpets, slowly filling the apartment until the doors of the rooms no longer shut. He began to collect ceramics, with a particular interest in the so-called “missing period” from 1350 to 1550, convinced that Islamic pottery had continued to develop, despite the lack of material evidence. The Keir Collection spans textiles, metalwork, book arts, carpets and pottery, among many other things, but his foremost passion was for lustreware – “the greatest gift the Islamic potter has made to mankind”.

De Unger’s eye for rarity and quality shines through his acquisitions. Of particular interest is a fragment of a 12th-century Mamluk playing card, the existence of which has helped establish the history of card games in the Near East. The ceramics expert John Carswell called de Unger’s collection of Fatimid lustreware “surely the finest collection in the world outside the Benaki Museum in Athens”. The entire collection was published in monographs in the 1970s and ’80s.

De Unger did not limit his collection to Islamic art: his interest also encompassed the Western Middle Ages, and he purchased the Ernst and Martha Kofler-Truniger collection of medieval Limoges enamels. This collection, which he sold in 1997, fell short of the $25 million estimated by Sotheby’s, only bringing in $5.5 million. The pain of that disaster was no doubt assuaged by his purchase in 2008 of a Fatimid rock-crystal ewer.

In a remarkable testament to his flawless eye, the ewer appeared for auction in Somerset as a “French claret jug” and sold for £220,000. By the time it reached Sotheby’s that October, it was expected to reach about £10 million, but was snapped up at the reserve of £3.24 million by the sole bidder, de Unger’s son, Richard, on behalf of the Keir Collection. Sotheby’s later valued it at £20 million.

At the heart of his compulsion, it seems, was a love of the hunt. Whether hiding the value of a manuscript from a bookshop owner by purchasing it with a number of less interesting works, or encouraging a lady to part with an heirloom by offering her niece a job as an au pair, his view was that “collecting is like hunting, in that not only does one derive aesthetic pleasure from the objects collected but the actual pursuit is pleasurable”.

It is easy to compare de Unger with the great gentleman collectors of the 19th and early 20th centuries, his father’s generation. Honoré de Balzac, in Le Cousin Pons, described men who “walk about as if in a dream, their pockets empty, their eyes vacant of all thought… These people are millionaires. They are collectors, the most impassioned men in the world”.De Unger himself felt “like someone belonging to an extinct species: the private collector who collects objects for their own sake and for his own pleasure and not for investment”.

As a child, one of de Unger’s favourite books was The Arabian Nights – one reason he gave for his love of Oriental miniatures. The image of a young boy in Budapest reading his way into another world is echoed by the Keir Collection itself, for years kept in the uncompromisingly English setting of de Unger’s Manor House in Ham. With such a stylistic disjuncture, each objet d’art evokes a different, parallel world – a sentiment that perhaps had some meaning to an émigré from the lost world of pre-war Hungary.

In the words of those great collectors of Japanese art, the Brothers Goncourt, 19th-century collectors indulged in a passion that “gives immediate gratification from all the objects that tempt, charm, seduce: they provide a momentary abandon in aesthetic debauchery”.

Edmond de Goncourt requested in his will that “those things of art which have been the joy of my life … shall not be consigned to the cold tomb of a museum…but I require that they shall all be dispersed under the hammer of the auctioneer, so that the pleasure which their acquisition has given me shall be given again…to some inheritor of my own taste”.

De Unger himself confessed to similar emotions. While many private collections have formed the basis of a museum (the core of the Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin comes from Friedrich Sarre’s important collection), there remains a dichotomy: in private collections, art is lived with, but in museums it is gawked at; objects become subservient to ideas, no longer merely items of aesthetic indulgence.

Pace Goncourt, the Pergamon Museum presents the collection with its ideal home. The Islamic galleries constitute the oldest museum of Islamic art in the West. Conceived as an addition to Berlin’s Museum Island by Wilhelm von Bode, the Pergamon Museum was purpose-built to house the German acquisitions from the Ottoman Empire, many of which came from find sharing on German excavations, notably the Pergamon Altar, the Ishtar Gate and the Miletus Gate. The fantastic Mshatta Façade came as a gift from Abdülhamid II to Kaiser Wilhelm II. In 2019 a massive refurbishment of the museum as a whole will be completed, and the Museum of Islamic Art will move into huge new galleries in one wing of the museum, where the Keir Collection will feature prominently.

Today it is hard for the visitor to the Pergamon Museum not to be overwhelmed with awe. The museum’s antiquities are vast, showy monuments to the ancient civilisations of the Near East, gifts that bear testimony to the alliance between the Ottoman and German empires in the late 19th century. Its vast halls put paid to the snobbery of Goncourt’s vision of “the cold tomb of a museum”.

For Stefan Weber, the new director of the Museum of Islamic Art, it is there not to store dead objects, but to “tell people about the things they wonder about”. Trained in architectural history, Weber has lived in Beirut and Damascus. His fluency in Arabic (he also speaks some Turkish and Farsi) is matched by his ease in tackling head-on the problems that a 19th-century collection faces in an early-20th-century museum in a thoroughly modern city. His vision for the new galleries is expansive. Curatorially he places great emphasis on the key heritage of the Pergamon – “the museum was built to architecturally reflect the objects it displayed”.

The Weber effect is clearly working. In 2010 the Islamic galleries attracted 600,000 visitors. Edmund de Unger chose not only the oldest but the best-visited museum of Islamic art in the western hemisphere.

In the catalogue of the Berlin exhibition in 2010, de Unger remarks that “each time I dust my Fatimid pieces I have the sensation one is in the presence of a masterpiece”. John Carswell has noted that de Unger arranged his lustreware so as to catch the morning sun. As Walter Benjamin once remarked, “For a collector – and I mean a real collector, a collector as he ought to be – ownership is the most intimate relationship that one can have to things. Not that they come alive in him; it is he who lives in them.” It is hard not to walk the corridors of the Pergamon Museum – through the Miletus Gate or into the Aleppo Room – and not feel that here, at least, one can inhabit the objects Edmund de Unger was so lucky to live with.

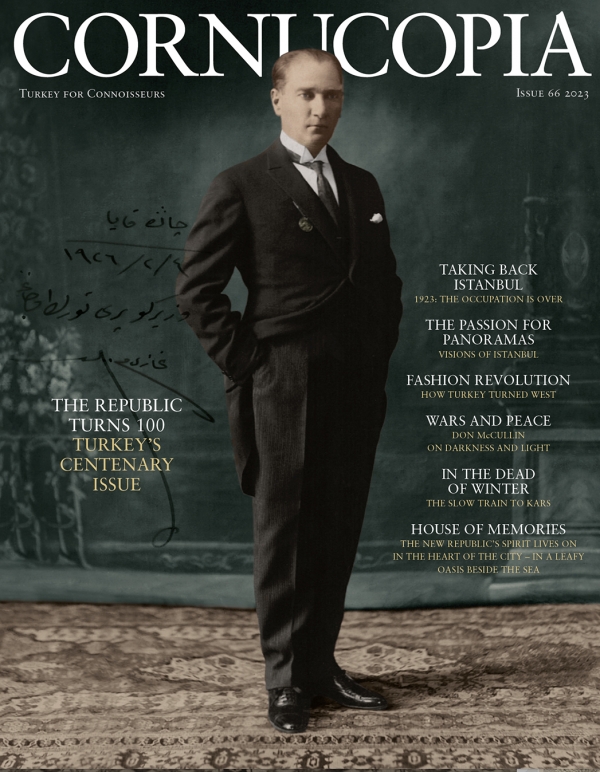

Issue 66, December 2023

Turkey’s Centenary Issue

Issue 66, December 2023

Turkey’s Centenary Issue

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now