Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionThe Sakıp Sabancı Museum celebrated 600 years of diplomatic relations between Poland and Turkey this spring. Jason Goodwin finds deep-rooted affinities between the two countries, and rediscovers the dashing warriors who faded from history

A warrior stands before you. His moustaches curl like the whiskers of a Tatar horseman and his hair is bunched at the back. His crimson silk-velvet coat reaches almost to the ground, figured with gold tassels and gold braid of woven thread. He has thrown back his sleeves to reveal a tunic of pearly silk, its low collar closed by a single jewelled stud. He wears a brooch, and a fur hat, and pantaloons stuffed into supple leather boots. His sword is at hand.

He stands at ease, but when he is fully armed he bristles with agents of death. In battle he bears a 20-foot lance, with a rattling pennant, and at his belt the curved sabre is joined by a sinister hammer that can crash through helmets of solid steel. He carries the short round bow of the steppe, the light, fast and accurate bow preferred by Mongols and Tatars and Turks and all other hard riders from the Eurasian grasslands; his saddle, too, is of the steppe. From his topknot to his quiver – itself a wonderful thing of dyed and chased leather, encrusted with gold filigree and pearls – this warrior is a dream of the East: but he is not a Tatar, or a Turk. He is a Latin-speaking Polish Catholic of the 17th century with, say, estates a day’s ride from Krakow or Lvov, and in choosing to dress in this exotic fashion he expresses his faith in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, in the Catholic Church, and the Golden Liberties of the szlachta, the multitudinous nobility of Poland–Lithuania.

He is a Sarmatian.

The recent show at Istanbul’s Sakıp Sabancı Museum celebrated the 600th anniversary of the first official contact between the Ottomans and that complex political entity known as the Commonwealth of Poland–Lithuania, which stretched from the Baltic down through Belorussia and Ukraine to the Black Sea.

The king whose emissaries visited Mehmed I in Edirne in 1414 was a pagan-born Lithuanian, Władysław Jagiello, who adopted Christianity to take the crown of Poland in 1386. In 1410 his coalition of Tatars, Poles, Lithuanians and Hungarians had crushed the Teutonic Knights at Grunwald, putting an end to centuries of German expansion towards the east. Mehmed was consolidating his position after the collapse of his father’s empire at Ankara in 1402.

The two sides shared many interests, and the meeting – to broker a peace in Hungary – was a friendly one. Over the next two centuries these empires, at the height of their power and prestige, often worked in concert to keep the Habsburgs in check, and to counter the rising power of Muscovy. Roxelana, the Ruthenian-born wife of Süleyman the Magnificent, kept up a friendly correspondence with the Polish king, stressing her particular affection for him as one of his former subjects, and the collapse of Hungary at Mohács in 1526 saw the two sides working hard to stop Hungary falling into the hands of the Habsburgs.

Some conflict was inevitable nonetheless, as the two empires competed for control of the so-called Wild Plains, which lie in the curve of the Dnieper between Kiev and Crimea. The Crimean Tatars launched annual raids into Polish territory, sometimes in advance of regular Turkish campaigns into Moldavia. They were matched by the Orthodox Christian Cossacks, who lived on islands on the Dnieper.

Regular Polish armies, fighting on the Baltic one moment, and on the Black Sea coast the next, were fabulously mobile, with horsemen outnumbering infantry by three to one and using Ottoman saddles, which placed less strain on a horse. When most European troops marched in a single mob, the Polish army already moved in divisions, and its elite cavalry, the Husaria, dominated the battlefield for most of the 17th century. They struck like a battering ram and manoeuvred like a London taxi, in spite of wearing extraordinary feathered wings, made of wooden runners covered in brass and velvet… Sheer weirdness was a respectable part of a batterie de guerre, too…

Jason Goodwin writes the Yashim series of detective novels, which feature a fictional Polish ambassador to the Sublime Porte. The Baklava Club, the latest adventure, is available from cornucopia.net

The catalogue of the recent exhibition *Distant Neighbour, Close Memories: 600 Years of Turkish–Polish Relations*, at the Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Istanbul, is available from cornucopia.net at £28.50

The Pera Museum will revisit the Ottoman–Polish theme with ‘Polish Orientalism’ (Oct 24, 2014 – Jan 18, 2015).

A website devoted to the anniversary celebrations, http://turkiye.culture.pl, is packed with news of Turkish–Polish happenings.

For more insights into the curious relationship between Turkey and Poland, see the blog poloniaottomanica.blogspot.co.uk

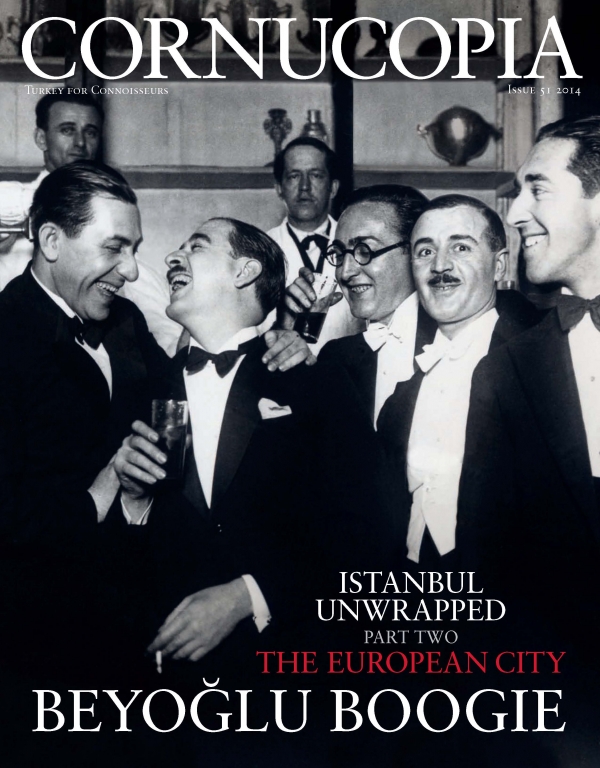

Issue 51, Summer 2014

Istanbul Unwrapped: The European City and the Sultan’s New City

Issue 51, Summer 2014

Istanbul Unwrapped: The European City and the Sultan’s New City

With 19th-century Istanbul in thrall to the music of Italy, an extraordinary theatre was born, the creation of one rather ‘odd character’. Emre Aracı tells a tale of comedy and tragedy

Black musicians, White Russian princesses, Turkish flappers… During the Jazz Age, Beyoğlu was a ferment of modernity and decadence. By Thomas Roueché

For 700 years, the European quarter was home to Genoese, Jews, Greeks and many others. Norman Stone charts the district’s changing fortunes

Maureen Freely recalls the artists and writers who enlivened her childhood with their flamboyant bravado and unspoken sadness

In the very thick of the city, with its fret and fuss, belching traffic and urban sprawl, lies a glade scented with linden blossoms. Here the young Sultan Abdülmecid built a jewel of a palace, grand but tiny, which is still a green oasis and place of escape. By Berrin Torolsan

Until the 20th century, visitors would sail serenely into Istanbul to disembark opposite the Topkapi. After this spectacular start, reality would set in. By David Barchard

For more than two centuries the Ottomans were obsessed by the elegance of the tulip and grew over 3,000 varieties, each characterised by almond-shaped petals drawn out into an exaggerated taper.

With its hundreds of different shapes, pasta is today one of the most widely consumed and enjoyed of all the staples

Across the Golden Horn from the Topkapı and the bazaars is the European City, where fortunes have for centuries been made and lost.

Patricia Daunt extols the palatial embassiess that adorn the heights of old Pera. Photographs by Brian McKee

As the old European quarters flourished in their seclusion, Sultan Abdülmecid had a dream – and expanded to the east

John Carswell introduces the mesmerising entries in this year’s Ancient and Modern Prize for original research

Issue 51, Summer 2014

Istanbul Unwrapped: The European City and the Sultan’s New City

Issue 51, Summer 2014

Istanbul Unwrapped: The European City and the Sultan’s New City

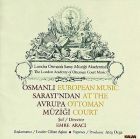

The London Academy of Ottoman Court Music, with Emre Aracı. Produced by Ates Orga,

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now