Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionMaureen Freely recalls the artists and writers who enlivened her childhood with their flamboyant bravado and unspoken sadness

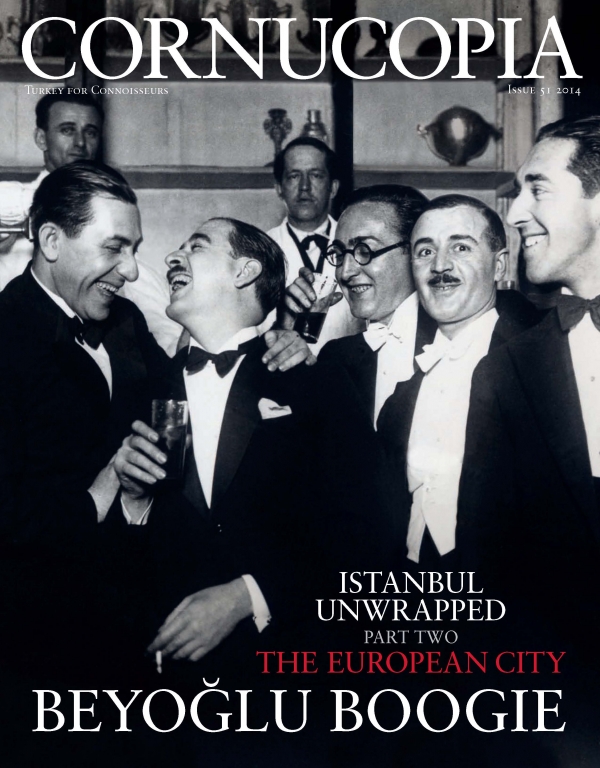

When I think back on the Beyoğlu I came to know as a child in the 1960s, what I see most clearly are the cafés where our mother took us for profiteroles and Viennese coffee, the bars and restaurants where we met our father afterwards, the meyhanes where the waiters looked after us so well, even when it was way past our bedtime, and the parties at which the great artist Aliye Berger would pinpoint the greater gifts that only she could see in us.

But what I feel most keenly are the sorrows that were left outside the door. I couldn’t have given a name to them then. And neither could I have identified the writers and artists and actors and directors whose smiles never betrayed the sadness I could see in their eyes as they walked in with arms outstretched. In those days, I saw mystery in their flamboyance. I conjured up extravagant tragedies.

Now I understand that for most of them the hardest thing was getting through the day. It was next to impossible to make a living in the arts in mid-20th-century Istanbul. It was difficult to travel or to stay in touch with the outside world. For those who combined literature with politics, it was far too easy to end up in prison.

But there was also Beyoğlu, to take your mind away from all that, if only for a few hours. In its cafés and meyhanes, writers and artists did not have to speak to be understood. “The waiters could tell from our eyes if we had no money,” Ülkü Tamer recalled. “They would plunk a bottle of soda water in front of us, and that would take us through to the evening.”

He was speaking about Baylan, the sumptuous establishment that was founded in the same year as the Republic and went on to lend its name to a literary movement, but I remember seeing the same silent arrangements beneath the chandeliers and Art Nouveau wall panels of Markiz. It would not, I imagine, have been much different in Nisuaz, the favoured late- afternoon gathering place for writers such as Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar and Sabahattin Ali before and during the Second World War. Many literary journals were conceived here, and many literary matters arbitrated – or at least caricatured. “Here it’s the same old story,” Sait Faik wrote to Orhan Veli in 1941. “Every Saturday, literary Istanbul meets at Nisuaz to pass its judgements.”

After dark, they would move on to Lambo, in Nevizade Sokağı, which Orhan Veli counted as his discovery and İlhan Berk described as being “as small as a tram”. Women writers seem to have felt particularly at home here. In later years, Leyla Erbil, Leyla Umar and Mina Urgan were all regulars. Monsieur Lambo was a communist. He would sit behind the counter reading Russian classics. When regulars were unable to meet their bills, he would sometimes ask them to pay with a poem or a few wise words.

Also in Nevizade was Lefter’s Meyhane, much loved by Orhan Kemal, Ülkü Tamer, Ece Ayhan and countless others. Night after night, the laterna in the back played one song only (‘A love will come to us from the islands’), but because the rakı flowed just as freely, no one ever found reason to complain.

In the early years of the Republic, the Çiçek Pasaji was best known as the home of Yahya Kemal’s favourite restaurant, the elegant Degustasyon. The Cumhuriyet Meyhanesi, located just around the corner, kept a special table for Atatürk. A few streets away there was Rejans, whose owners were said to have danced for the Bolshoi before the revolution. In its early years, their restaurant was a gathering place for Russia’s fleeing aristocracy. By the time I arrived, all the establishments in this neighbourhood were dusty and disintegrating but, now more than ever, the Çiçek Pasajı had become a place where anyone (any man, that is) could go with their friends to spend an evening drinking arjantins of beer with plate after plate of fried mussels, saying whatever they couldn’t say at home.

Late at night, rebellion seemed almost possible. In the Neşe Meyhanesi, in the nearby Krepen Pasajı, the dream began at midday. There was, my father tells me, a group of writers that met before lunch every Friday to synchronise their first rakı with the midday call to prayer.

When that meyhane closed its doors in the mid-Sixties, the group moved on to Seviç, in the Çiçek Pasajı. This was not the last time it had to move camp but somehow it kept going. Aydın Boysan, one of the group’s founding members, now in his mid-nineties, is alleged not to have missed a single meeting.

Kulis, with its velvet curtains and its walls of mirrors, was more refined, in a European sort of way. It was a place where a woman felt protected. In the loo was a table at which ladies could sit and smoke and take a break from the mirrors, if they so wished. Artfully arranged behind the ashtray was a giant Spanish dancer doll, a selection of make-up, and a bottle of Johnny Walker Black.

Like Papirüs across the street and the Art Deco bar at the Park Hotel, Kulis was mostly a journalists’ haunt, through which writers, artists, diplomats, spies and defectors from the bourgeoisie also wandered. Many were theatrical enough to outdo the actors and directors from the nearby Yeşilçam studios. There was a great deal of posturing and tragic laughter. There were passionate soliloquies, and long, meandering anecdotes that ended with a slap on the table, and wars of words that would have ended in death if anyone had been able to remember them. But there was, nonetheless, a sense of common cause – an agreement, at least, that those living on the margin could not do without their friends. Sütçüyan, the owner of Kulis, loved his regulars like children. If they hadn’t turned up for a few days, he would go and see them, just to make sure they weren’t ill.

But by the end of the 1970s life had become as difficult for the owners of Beyoğlu’s cafés and meyhanes as it was for its bohemians. Many of these owners were Greek and Armenian, and the middle years of the 20th century were not kind to them.

The exodus began with the riots of 1955, and continued with the Cyprus crisis of 1964. As the Greeks and Armenians left, the city’s new immigrants moved in to take their place. The streets became more dangerous. Establishment after establishment burned down. The film industry died, taking the Yeşilçam studios with it. When Monsieur Lambo was forced to close his meyhane, he turned it into a shoe shop. Not long afterwards, he committed suicide. And it seemed as if the old Beyoğlu was gone for ever.

But over the past two decades, it has been slowly, very slowly, coming back into its own. It is a little shinier these days – and a little too conscious of its past. But never mind. It is heartening to see Ara Güler’s photographs of mid-20th-century Beyoğlu on the walls of the Café Ara in Galatasaray. And when I go to Cihangir or Asmalımescit, I can still find cafés and meyhanes that serve as second homes for the artists and writers of the neighbourhood. I can see them leaving their sorrows at the door, and walking in with outstretched arms, and settling into a chair to be cared for by silently compassionate waiters, and making do with soda water while they draw, and write, and dream of wilder nights. The spirit of old Beyoğlu is still with us.

Maureen Freely is a novelist and translator and Professor of English and Comparative Literary Studies at Warwick University

With 19th-century Istanbul in thrall to the music of Italy, an extraordinary theatre was born, the creation of one rather ‘odd character’. Emre Aracı tells a tale of comedy and tragedy

Black musicians, White Russian princesses, Turkish flappers… During the Jazz Age, Beyoğlu was a ferment of modernity and decadence. By Thomas Roueché

For 700 years, the European quarter was home to Genoese, Jews, Greeks and many others. Norman Stone charts the district’s changing fortunes

In the very thick of the city, with its fret and fuss, belching traffic and urban sprawl, lies a glade scented with linden blossoms. Here the young Sultan Abdülmecid built a jewel of a palace, grand but tiny, which is still a green oasis and place of escape. By Berrin Torolsan

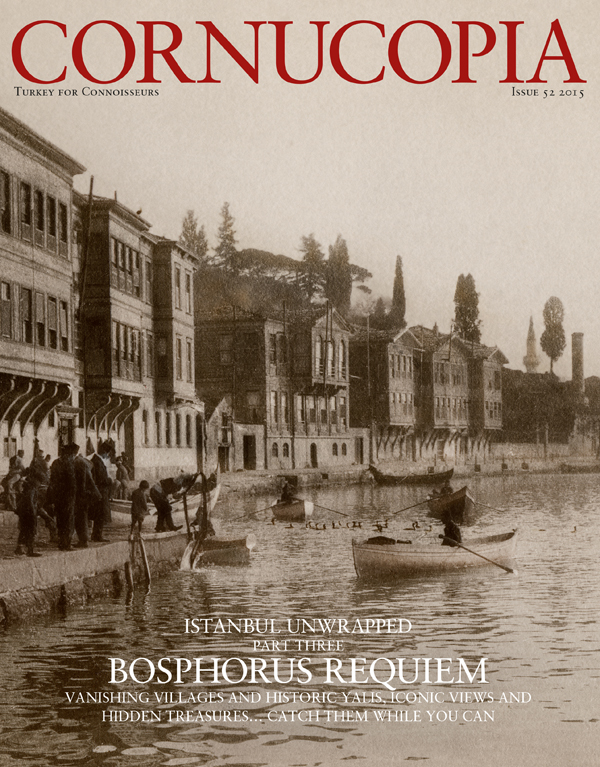

Until the 20th century, visitors would sail serenely into Istanbul to disembark opposite the Topkapi. After this spectacular start, reality would set in. By David Barchard

For more than two centuries the Ottomans were obsessed by the elegance of the tulip and grew over 3,000 varieties, each characterised by almond-shaped petals drawn out into an exaggerated taper.

With its hundreds of different shapes, pasta is today one of the most widely consumed and enjoyed of all the staples

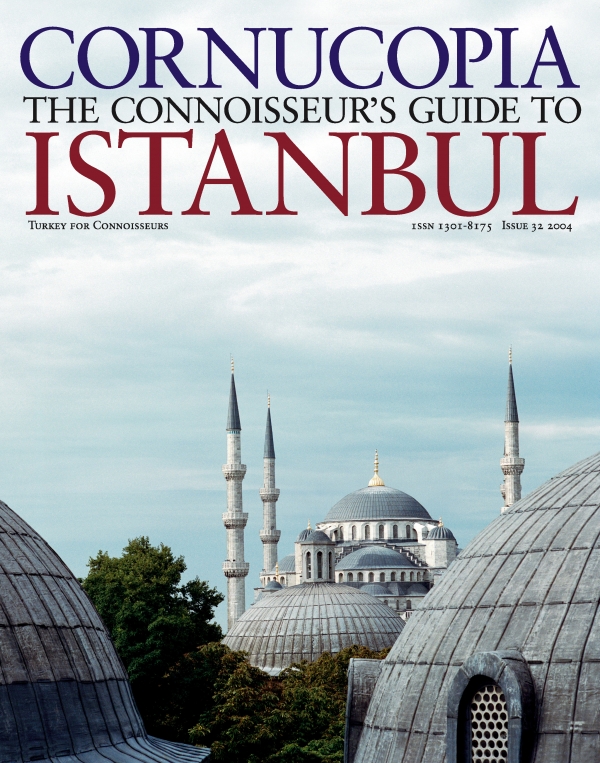

Across the Golden Horn from the Topkapı and the bazaars is the European City, where fortunes have for centuries been made and lost.

Patricia Daunt extols the palatial embassiess that adorn the heights of old Pera. Photographs by Brian McKee

As the old European quarters flourished in their seclusion, Sultan Abdülmecid had a dream – and expanded to the east

The Sakip Sabanci Museum has just celebrated 600 years of diplomatic relations between Poland and Turkey. Jason Goodwin finds deep-rooted affinities between the two countries

John Carswell introduces the mesmerising entries in this year’s Ancient and Modern Prize for original research

Issue 51, Summer 2014

Istanbul Unwrapped: The European City and the Sultan’s New City

Issue 51, Summer 2014

Istanbul Unwrapped: The European City and the Sultan’s New City

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now