Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionIn the very thick of the city, with its fret and fuss, belching traffic and urban sprawl, lies a glade scented with linden blossoms. Here the young Sultan Abdülmecid built a jewel of a palace, grand but tiny, which is still a green oasis and place of escape. By Berrin Torolsan

Hidden from the hillsides of concrete that line the valley of the Fulya river, the walled garden of the Ihlamur Kasrı – the Linden Pavilion – is an oasis. At the beginning of June, the magic is all the stronger: the heady fragrance of the linden trees lifts you into another world. These are broad- leaved limes (Tilia platyphyllos), said to be the most scented variety. Sadly, many were felled when the old garden walls were torn down a few years ago.

The young Abdülmecid I loved the tranquillity of this spot, and it is here that he received the Turcophile French writer, poet and politician Alphonse de Lamartine in 1849, after his failed bid for the presidency of France against Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte. The Frenchman was surprised to be entertained by the glamorous young sultan in what was at that time a modest farmhouse. Abdülmecid granted him an estate on the Aegean where he could spend the rest of his life. But Lamartine returned to France to sort out his affairs, and died in Paris years later, too poor to go into exile. The estate reverted to the Ottoman treasury.

A progressive thinker who opposed slavery and the death penalty and was lionised for his heroic stand against tyranny, Lamartine was passionate about Turkey. “If one had but a single glance to give the world,” he wrote, “one should gaze on Stamboul.” Abdülmecid, for his part, spoke fluent French, was highly educated, one of the best calligraphers of his time and fond of Western literature and music. David Wilkie painted a portrait of him for Queen Victoria upon his succession at 16, and noted his enthusiasm for art. In 1847, Liszt was one of many composers welcomed to his court. The sultan had begun a building spree that included Dolmabahcçe Palace on the Bosphorus, a palace opera house and numerous public buildings – hospitals, schools, the first Western-style university, mosques, barracks, clock towers and the first railway: cornerstones of a Europeanised Ottoman world. Now, in his favourite linden park, he would order a twin-pavilioned maison de plaisance, of the sort popular in the 19th century among royalty keen to escape the stultifying formality of their palaces.

Set back from the entrance, veiled by magnolias and ginkgo trees, the Merasim Köşkü, or Ceremonial Kiosk, is the focus of the Ihlamur Kasrı. An elegant pond reflects the garlands, acanthus leaves, festoons, scrolls and urns that adorn the sandstone façade. Marmara marble is used for the fluted columns and trellised balustrades of the horseshoe staircase. “The stairs are always the delight of a Balyan palace,” declared Godfrey Goodwin, the late doyen of Ottoman architectural history – and this building is in fact one of the best examples of the Balyan style.

The architect, Nikoğos Balyan, belonged to a dynasty of Istanbul-born architects and contractors responsible for many imperial buildings. Trained in Paris, he was inspired by Rococo and Neoclassical architecture, everything in fact from Lebrun’s Versailles to Garnier’s Paris Opéra. He used his French Baroque and Rococo vocabulary with playfulness and an almost Oriental wit. Had the ageing Alphonse de Lamartine made it back to this place, he would have been reminded of home.

Inside Ihlamur, Balyan, and probably his designers – Charles Séchan of Paris, who was in Istanbul to decorate the theatre at Dolmabahçe, and William Gibbs Rogers of London, who furnished the palace – let their imagination take wing. The Ceremonial Kiosk is a neat rectangular prism. Three rooms of identical width line up along the front: an entrance hall in the centre, with an anteroom to the right and a reception room to the left, both of which lead out to terraces.

Behind the anteroom is a washroom with an exuberant marble basin, and stairs leading down to where guards and servants presumably waited. The walls are in beautifully executed faux marbling, with the exception of the reception room, whose lapis lazuli effect has lost none of its lustre after 160 years. The gilded pediments, rosettes, overdoors, stuccoed shells, swags, baskets of fruit and garlands of flowers lavished on the cornices and ceilings entwine around the flower still lifes in more gentle, subdued colours. Moss roses, wallflowers, violets, sweet peas, irises and tulips – all no doubt grown in the garden – repeat in the porcelain surrounds of the three fireplaces and in the doorknobs. When the sun pours in through the French windows, it hits the sapphire-coloured Venetian- glass doors, setting the jewel- like splendour alight. Tall crystal mirrors create theatrical optical illusions to left and right. A cupola crowns the hall; a powerful barrel vault spans the reception room. All this in a building that could easily fit into many a Paris drawing room.

This exercise in illusion is certainly Baroque in feeling, but it is classical in proportion – an exquisite conceit, as formal and festive as an aria from Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore, of which the young sultan was so fond.

The second, more restrained building, the Maiyet Köşkü, or Retinue Kiosk, had the perfect view of this Baroque pearl. Its plan is in the Ottoman tradition – four square rooms in the four corners, leading off a central hall or sofa. It was here, on June 25, 1861, that Abdülmecid, reformer and patron of the arts, died of tuberculosis at the age of 38, just after the linden blossoms had passed.

Ihlamur Kasrı is open daily except Monday and Thursday, 9.30am–5pm; +90-212 236 9000; millisaraylar.gov.tr. There is no easy public transport, so take a taxi or walk 10 minutes downhill from Nişantaşı, or 15 minutes inland from Beşiktas

With 19th-century Istanbul in thrall to the music of Italy, an extraordinary theatre was born, the creation of one rather ‘odd character’. Emre Aracı tells a tale of comedy and tragedy

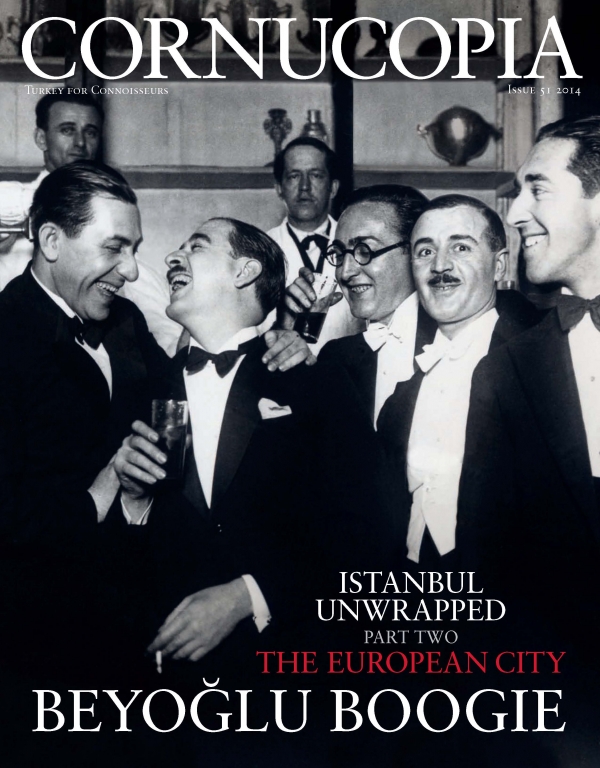

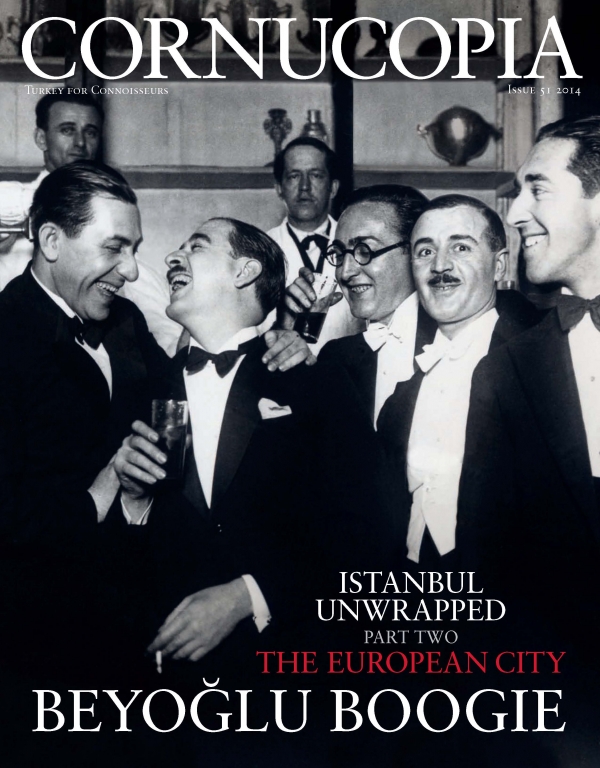

Black musicians, White Russian princesses, Turkish flappers… During the Jazz Age, Beyoğlu was a ferment of modernity and decadence. By Thomas Roueché

For 700 years, the European quarter was home to Genoese, Jews, Greeks and many others. Norman Stone charts the district’s changing fortunes

Maureen Freely recalls the artists and writers who enlivened her childhood with their flamboyant bravado and unspoken sadness

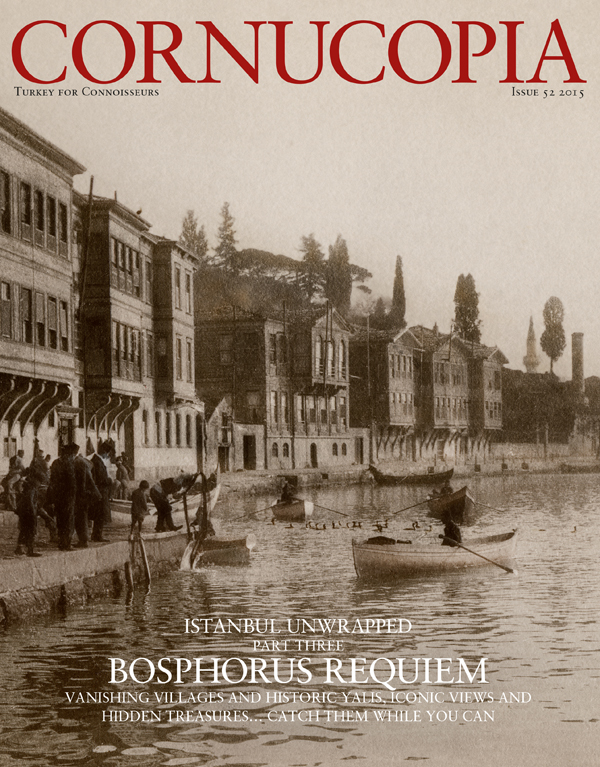

Until the 20th century, visitors would sail serenely into Istanbul to disembark opposite the Topkapi. After this spectacular start, reality would set in. By David Barchard

For more than two centuries the Ottomans were obsessed by the elegance of the tulip and grew over 3,000 varieties, each characterised by almond-shaped petals drawn out into an exaggerated taper.

With its hundreds of different shapes, pasta is today one of the most widely consumed and enjoyed of all the staples

Across the Golden Horn from the Topkapı and the bazaars is the European City, where fortunes have for centuries been made and lost.

Patricia Daunt extols the palatial embassiess that adorn the heights of old Pera. Photographs by Brian McKee

As the old European quarters flourished in their seclusion, Sultan Abdülmecid had a dream – and expanded to the east

The Sakip Sabanci Museum has just celebrated 600 years of diplomatic relations between Poland and Turkey. Jason Goodwin finds deep-rooted affinities between the two countries

John Carswell introduces the mesmerising entries in this year’s Ancient and Modern Prize for original research

Issue 51, Summer 2014

Istanbul Unwrapped: The European City and the Sultan’s New City

Issue 51, Summer 2014

Istanbul Unwrapped: The European City and the Sultan’s New City

The London Academy of Ottoman Court Music, with Emre Araci

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now