Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital Edition

Jean-Baptiste Vanmour (1671-1737)

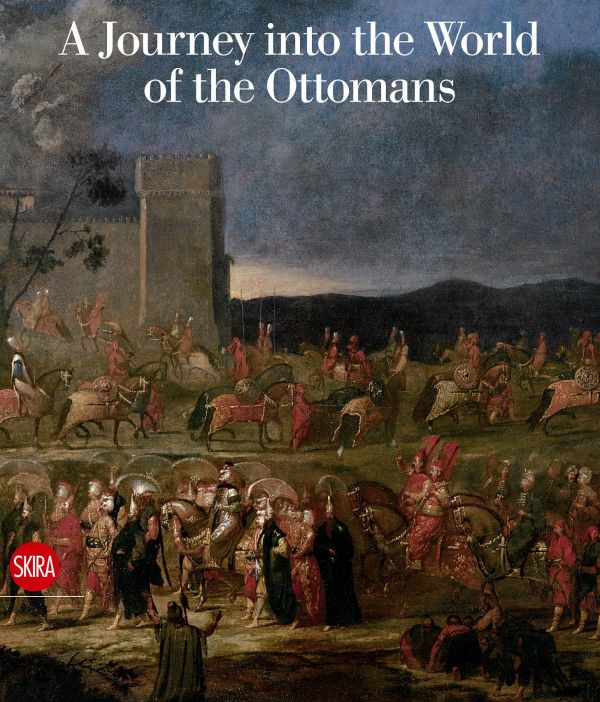

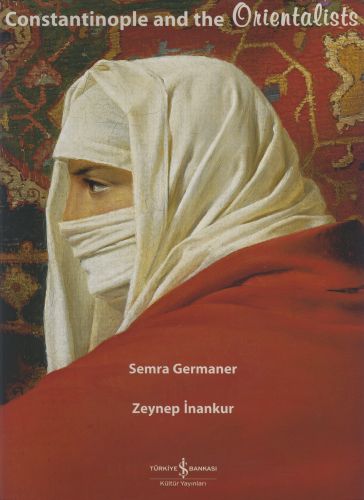

Jean-Baptiste Vanmour was one of the most important “orientalist” artist: this publication is the most comprehensive survey of his works. Orientalism can be defined as a historical and cultural event, which has been uniting various aspects of cultural life for a number of centuries – literature, fine arts, architecture, music and philosophy. A “vision” of the East – positive or negative – based on imagination or historic facts, it has generated an exotic image in our consciousness, which has its own right to existence. The Franco-Flemish artist Jean Baptiste Vanmour (1671-1737) was the art-biographer of the XVIII century Ottoman Empire. He left a very important legacy – pictorial evidences which can be considered as historical illustrations of all the aspects of XVIII century Ottoman life: from diplomatic ceremonies in the Ottoman court to everyday events of Istanbul multinational society.

Few painters have left such a complete record of Istanbul, or indeed of any other city, as Jean Baptiste Vanmour. Born in French Flanders in 1671, he came to Istanbul in 1699, at the age of eighteen, in the suite of the French ambassador, the Marquis de Ferriol. As far as is known, he did not leave the city until his death in 1737. Between those dates he painted hundreds of pictures. They reveal Vanmour as, pre-eminently, the artist of diplomacy and dress.

The Ottoman Empire was then so powerful, and so fascinating, that most ambassadors wished to commission commemorative pictures of their audiences with its two principal figures, the grand vizir and the sultan. Vanmour painted many pictures of French ambassadors’ audiences, and of other subjects (for example pictures, now lost, of Bosphorus fishing techniques for the French Ministry of Marine Affairs). As a reward, in 1725 Vanmour received the unique (though to his dismay unpaid) office of peintre ordinaire du roi en Levant. His loyalties were not restricted to France. The Dutch ambassador, Cornelis Calkoen, paid Vanmour the honour of including him in the very small number of people permitted to accompany him into the Divan and the throne-room in the Topkapi Palace when he presented his credentials on September 14, 1727.

Calkoen was sufficiently convinced of the importance of his seventy pictures by Vanmour to stipulate in his will that they should remain together after his death. They now belong to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, which has sent them to an exhibition at the Topkapi Palace. There they are on show with miniatures by Levni, Vanmour’s Turkish contemporary. The two artists sometimes painted the same subjects (see Connoisseur, page 7).

Vanmour and his studio painted many other ambassadors’ audiences - Austrian and Venetian as well as French and Dutch. Thanks to Vanmour, there is a better visual record of embassies to Istanbul than to any other court, a mark of the importance of the Ottoman Empire in Europe’s diplomatic system and the fascination it held for his contemporaries.

Vanmour was also a painter of dress, in an age when it was a crucial indicator of rank, wealth, identity and allegiance. In 1707 he had been commissioned by the French ambassador, Ferriol, to paint 100 pictures of different officials and nationalities of the city - Turkish women, Jewish women, Bulgarian shepherds, the ecumenical patriarch - in their costumes. After a stormy embassy, in which he failed to be received by the sultan for refusing to remove his sword before entering the throne-room, Ferriol returned to Paris. There he arranged for Vanmour’s pictures to be engraved in a volume entitled Recueil de cent estampes représentant différentes nations du Levant (1712-13). Such was the ambassador’s vanity that only his name, and not that of the artist, is mentioned in the preface. However, Recueil de cent estampes was the main source for those images of turqueries, by artists such as Boucher and Guardi, so popular in eighteenth-century Europe; it was immediately translated into English, German, Spanish and Italian. Vanmour had single-handedly brought the Ottoman Empire into the visual repertory of Europe.

Vanmour also painted other scenes whose details, and accompanying notes written in an anonymous hand, provide invaluable information about the Ottoman past: for example the picture in this exhibition of a woman taking her young daughter to embroidery school is a reminder of the role of women in this important Ottoman handicraft. If most women were not taught to read and write, they were at least taught to sew. The picture of Calkoen advancing towards the grand vizir’s Divan shows janissaries, on their payday, rushing to eat their pilav. If they remained motionless, it was a sign that they were preparing another of their frequent rebellions.

Vanmour’s pictures of Patrona Halil and his close friend and fellow rebel, Muslu Bese, who in 1730 led the first popular revolution in Ottoman history, are rare individual portraits of Turks not from the Ottoman elite - indeed, described in the notes as of “very low birth”. Probably painted in the few weeks in which Patrona Halil held power before his murder on the new sultan’s orders, such a portrait suggests that Vanmour was familiar with the inner political life of the Ottoman capital, as well as the diplomatic ceremonial of the European embassies.

The exhibition, which has travelled from Amsterdam, signals an advance in our knowledge of the mysterious figure of Jean Baptiste Vanmour. It is still not known, however, whether he visited some of the other cities he is alleged to have painted, such as Ankara, Aleppo, Isfahan and Jerusalem. In the catalogue to the Amsterdam exhibition, Duncan Bull points out that Vanmour probably had stock scenes, figures and settings which he frequently reused in different pictures.

A complete catalogue of works by Vanmour and his assistants is needed. Many of his finest pictures, having passed through the salerooms in the past twenty years, are now hidden in private collections in London, Paris and Istanbul.

Nevertheless, this exhibition brings some of Vanmour’s pictures back to the city where they were painted, for the first time since Calkoen’s return to the Netherlands in 1744. It is a reminder that Istanbul was an artistic, as well as a political and commercial, meeting place of East and West.

Paintings by Vanmour from the Rijksmuseum went on show at the Topkapı with works by Levni in 2004

Out of Print

Out of Print

Out of Print

Out of Print

Buy from Amazon

Buy from Amazon

1. STANDARD

Standard, untracked shipping is available worldwide. However, for high-value or heavy shipments outside the UK and Turkey, we strongly recommend option 2 or 3.

2. TRACKED SHIPPING

You can choose this option when ordering online.

3. EXPRESS SHIPPING

Contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net for a quote.

You can also order directly through subscriptions@cornucopia.net if you are worried about shipping times. We can issue a secure online invoice payable by debit or credit card for your order.

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now