Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionIn her diary of April 1907, Gertrude Bell describes arriving in Sagalassos: “We travelled to the mountains and kept climbing until I thought no city could ever be built this high. At noon I suddenly saw a beautiful theatre that was still half-covered with snow… I spent three wonderful hours at the end of which I understood why the Psidians had built their city so high in the mountains.’

Although the site was well known to 19th-century travellers, it was not until 1990 that it begun to be properly excavated under the Belgian archaeologist Marc Waelkens, who told Cornucopia’s Thomas Roueché, ‘With a population of only 5,000 – that’s one-fortieth the size of Ephesus – the city had the oldest bath complex of Roman type in Asia Minor, and one of its oldest and widest colonnaded streets, wider even than any contemporaneous streets in Ephesus. Every decorative and architectural innovation that made its way to Ephesus from Rome had reached Sagalassos within five years.’

The extensive site that Waelkens has spent a quarter century excavating, includes an imperial bath, which had a metre-high head of Hadrian that Waelkens describes as “the most beautiful portrait of the Emperor in the world.’

The snowy scenes that the intrepid Bell captured are shown in Cornucopia 48 in a feature on Sagalassos, one of the most romantic ancient sites in Anatolia. The most important city in Imperial Roman Psidia, a region that roughly corresponds with the modern province of Antalya, Sagalassos is in a spectacular position in the foothills of the Taurus Mountains, above Turkey’s Lakes District, some 1500 metres above sea level.

Many of the items from Sagalassos, including the colossal head of Hadrian I, are now on display in the Archaeology Museum in nearby Burdur.

‘We travelled to the mountains and kept climbing until I thought no city could ever be built this high. At noon I suddenly saw a beautiful theatre that was still half-covered with snow… I spent three wonderful hours at the end of which I understood why the Pisidians had built their city so high in the mountains.’ – Gertrude Bell in 1907

In the late summer of 1983, two archaeologists stood on the slopes of the western Taurus Mountains amongst the ruins of the city of Sagalassos. Mount Akdağ towered over the ancient metropolis of Pisidia; high above the two men an eagle soared, leading them further into the site. For Marc Waelkens, his first visit was almost a religious revelation. “It seemed to me,” he later recalled, “that this eagle, majestic as it rose and soared above, leading us through the ruins of this magnificent city, was the very incarnation of Zeus himself.”

The city of Leuven is a place of quiet northern charm, a far cry from the wild, dramatic, fearsome beauty of Sagalassos. Marc Waelkens’ high-ceilinged office in the heart of the research-driven university town is spartan, dominated by a relief map of Sagalassos, while on the walls hang a series of enormous photographs of the city’s monuments. On the table lies a copy of the extraordinary catalogue Sagalassos: City of Dreams, produced to accompany the eponymous exhibition at the Gallo-Roman Museum in Tongeren – an exhibition he was intimately involved with from the beginning.

Waelkens’ eyes light up as he begins to talk about Sagalassos; he says he is “married” to the city. Quickly it becomes clear one is in the presence of someone whose life has been dedicated to a single passion. Sagalassos is Waelkens’ life’s work, his Gesamtkunstwerk. Captivated as a young boy by the stories of Heinrich Schliemann’s discovery of Troy, as told in a Belgian comic strip, Waelkens announced to his father that he wanted to become an archaeologist in Turkey. His father responded with incredulity, as fathers do in such stories.

Waelkens embarked on a steady career trajectory through the universities of Belgium – famous for their political and religious factionalism – and excavations across the Mediterranean. Eventually, in 1983, he accompanied the renowned Hellenist Stephen Mitchell on his first fateful expedition to Sagalassos, as part of Mitchell’s Pisidia Project.

Charming, kind and indefatigably knowledgeable, Waelkens is perhaps the archaeologist’s archaeologist. Many digs are notoriously fraught with difficulties – hot summers, crowded dig houses and big egos. Mistakes of the past, whether a result of lack of technology, the hubris of former excavators or the damage wrought by looters, can severely impede the archaeological process, dramatically altering the archaeological record, and rendering attempts to recapture the past architecture of cities impossible. At Sagalassos, Waelkens inaugurated an astonishingly meticulous excavation, deploying interdisciplinary approaches, new technological perspectives and a steadily growing team of experts from Belgium, Turkey and more than a dozen other countries.

From the start, Sagalassos presented Waelkens with a unique situation. Its remoteness had left the site almost completely untouched; when Waelkens and Mitchell first visited, thick layers of pottery and glass crunched underfoot. Over the next 25 years, Waelkens would collect, order and collate fragments large and small, man-made, faunal and floral, from every corner of the site and its vast territory. He also identified changing settlement patterns, reconstructed climatic and vegetation changes, as well as anthropogenic (farming) or natural sedimentation of valley bottoms and slope erosion. He identified the provenance of consumption goods and changing cooking practices, that of raw materials used for craft production or in the building industry, and even identified the content of ceramic vessels (cooking pots, amphorae, storage vessels, serving plates), thereby reconstructing subsistence and trading patterns. All of this was a scrupulous operation of Sisyphean proportions, and one that transformed Sagalassos – a site barely known from the historical record – into one of the Mediterranean’s most important excavations.

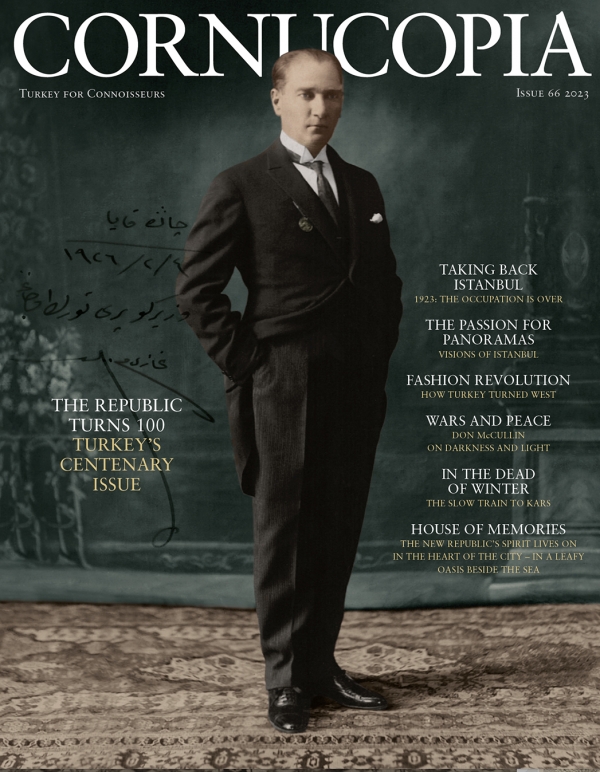

Issue 66, December 2023

Turkey’s Centenary Issue

Issue 66, December 2023

Turkey’s Centenary Issue

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now