Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionExiled by Stalin in 1929, Trotsky went to live on the Princes Islands near Istanbul. For four years he fished, wrote and developed the doctrine of Trotskyism. Remarkable photographs from the David King Collection show a quiet, ordered existence. Norman Stone uncovers the plotting that lay behind it

By the shore on the island of Büyükada in the Sea of Marmara there stands a large, ugly and ruined house, in style a mixture of Leipzig railway station and Sandringham. The garden, untended for decades, stretches down to the sea. The roof has almost fallen in. But it has a history.

The house belonged to Izzet Pasha, the great hatchet-man of Sultan Abdülhamid, but its most famous occupant, for four years in the early Thirties, was Trotsky. The island – largest of an archipelago and easily visible from Istanbul on a clear day – was mainly inhabited by rich Greeks. It was known to history as Prinkipo, because in Byzantine times various princes were exiled there, sometimes blinded, to remove them from the political board.

Since then, Büyükada has had some odd occupants. The man who, in 1917, courtesy of the German General Staff, organised Lenin’s journey across Germany from Zurich to St Petersburg, lived here. He made his money running the Ottoman tobacco monopoly. Another occupant was de Vere Townsend, the British general who had surrendered to the Turks in 1916 after a gallant stand at Kut-el-Amara. This old boy became something of a social lion in wartime Istanbul; fanatically pro-Turkish, he was used in 1918 as an intermediary in arranging the armistice. But the most famous occupant of Büyükada-Prinkipo was Trotsky.

In February 1929, Trotsky, expelled from the Soviet Union, was established in Izzet Pasha’s unlovely pile. And here he remained for four years, until moving on via France and Norway to his final stopping place in Mexico, where in 1940 Stalin’s murderers caught up with him. Revolutions famously eat their children, and Stalin, of course, made a vast banquet of them. But Trotsky proved indigestible. When Lenin died in 1924, Trotsky was in many ways the obvious successor. He had been Lenin’s right-hand man and had proved a brilliant organiser of the Red Army, travelling the length and breadth of civil-war Russia in his armoured train. He also knew quite a bit about economics, lecturing the Party on how to manage agricultural prices. Before the Revolution, he had been (like Marx, too, for a time) a journalist, and his accounts of the Balkan Wars are still well worth reading. On Büyükada, he survived by his pen – the autobiography and the three-volume history of the Russian Revolution, the first volume of which, at least, deserves to survive. Just as Napoleon created Bonapartism on St Helena, so Trotsky developed Trotskyism on Prinkipo. The legend of the romantic revolutionary, of ‘permanent revolution’, leads straight to Che Guevara, still agonising today on countless student T-shirts and posters.

The trouble with Trotsky was that, for all his enormous gifts, he could not manage the Bolsheviks as Stalin could: he was too vain and self-obsessed. And how he despised those unlettered, jumped-up peasants promoted by Stalin. Maybe the heart of the whole problem was that he was too much the clever Jew. When Party congresses had to choose between Stalin’s line and Trotsky’s, they chose Stalin’s. Trotsky was the ultra-revolutionary, wanting to use backward Russia as a base for operations in Germany, or China, or anywhere. In his opinion, Russia (‘the Russia of icons and cockroaches’) was too backward: she needed German skills. Boot the peasants around, ignore and suppress the native Russian revolutionary tradition, and concentrate your fire on making trouble in Germany. That policy failed. In 1921, the Party opted for the ‘New Economic Policy’, making concessions to the free market and the peasants. In October 1923 an effort to promote revolution in Germany failed – its only serious consequence was that it provoked Hitler into staging his Munich Putsch. Trotsky, producing glittering phrases to audiences of suspicious, piggy-eyed provincial power-brokers, had less and less to offer, and when Stalin proclaimed the policy of “socialism in one country” – ie, forget the international revolution – Trotsky was isolated. Oddly enough, he had even voted for his own downfall. In 1920, the Party had resolved that no outward dissidence or opposition would be allowed: Trotsky voted for that.

In 1923, Lenin’s own testament was leaked, and, in it, he warned that Stalin was dangerous and should be replaced. Trotsky, after Lenin’s death, voted that the testament should not be made public: it was an effort to appease Stalin, and it failed. In 1927 he was expelled from his Kremlin residence, and, after a pathetic street demonstration by his supporters on the tenth anniversary of the Revolution, he was exiled to Alma-Ata in Kazakhstan.

Eisenstein at the time was making his famous film on the storming of the Winter Palace in 1917. Orders went out that Trotsky was not to be shown. Some of his followers were hunted down and killed, but Trotsky himself was too big game: in the end, early in 1929, Stalin decided just to push him abroad. On a ship from Odessa, he arrived in Istanbul.

But why Turkey, now so firmly allied with the West? The fact was that she was, in 1929, on good terms with the Soviet Union. Khrushchev made an odd outburst at a meeting of the Central Committee in 1957. How mad it had been of those in charge of the Soviet Union to make an enemy of Turkey back in 1945; Turkey had been a useful associate, and in Izmir there had even been a square named after the Soviet Marshal Voroshilov. But Stalin had insisted on trying to take the Straits, and Turkey had joined Nato.

Khrushchev was right: republican Turkey had indeed been quite a good associate for the USSR. The two countries had emerged at much the same time after the First World War, and they had shared some enemies, especially the British and French. Soviet gold and weaponry had greatly helped the Turkish Nationalists to defeat first the French and then the Greeks. In acknowledgement, the Nationalists described themselves as revolutionaries and called their ministers ‘commissars’. Once started up, they shared with the Soviets what might be called a ‘modernisation project’ – turning backward peasants into literate citizens. The Atatürkists turned their old and difficult Arabic script into Latin so that their Turkic language could be adapted for the purposes of mass literacy. The Soviets did the same with Cyrillic in Central Asia. Oddly enough, Atatürk signed a photograph for the Soviet ambassador in Latin script in 1924 (I have seen it on display in the Russian embassy in Ankara), though it was not until 1928 that the Latin script was introduced. The iconography of both countries, from ‘revolutionary porcelain’ through Five Year Plans to the ubiquitous statue of the Leader, is strikingly similar.

Of course the basis of the bargain was clear enough – that the Soviets would not encourage Turkish Communists, and that the Turks would not encourage Turkic nationalism, let alone Western intervention. It was forbidden, in inter-war Turkey, to import literature from exiled Caucasus people, and some pan-Turanian nationalists even fled the country. The two countries had co-operated reasonably easily on the designing of a new frontier. The Soviet Union had handed back to Turkey the districts lost to Tsarist Russia in 1878 – Kars (still very obviously a provincial Russian town, in part), Artvin and Ardahan. The new border favoured Georgia, but not Armenia, and the Soviets went out of their way to make small concessions where necessary.

In 1926 Pravda published the congratulatory telegram of the Turkish foreign minister, Tevfik Rüştü Bey – the usual platitudes (“I entirely share your opinion that the settlement of the question as regards the frontier is new evidence of the friendship that exists between Turkey and the people of the Soviet Union”). But there are platitudes and platitudes, and this one meant something. At the time, of course, it mattered that the Turks were at odds with the British as to who should have the Mosul oil wells. They were also at odds with Mussolini’s Italy, then occupying, imperialist-fashion, the Dodecanese islands off the Turkish coast, including Rhodes.

So the Turks needed the Soviets, who were promoting an anti-imperialist bloc, including Afghanistan and Iran. Turkey had led the way in this, with a treaty of neutrality or non-aggression (in effect, alliance) in 1925. There had been a very amicable meeting at Odessa between Tevfik Rüştü Bey and Chicherin, the then Soviet foreign affairs commissar, in 1926. In 1927, on easy terms, Turkey had almost four million dollars’ worth of Soviet artillery. In 1929 the non-aggression treaty was extended. Various economic arrangements followed. Turkey became the largest non-Communist recipient of Soviet aid and there are still, dotted around in Anatolia, gigantic factories to mark this – especially a textile one in Kayseri which, along with a credit of eight million gold roubles, was part of a package designed to keep Turkey friendly, at a time when Stalin feared a general attack by the West.

Was Trotsky part of this package? We do not know the Turkish side of this, as yet, because the relevant archives are only now being declassified. But we do know that after a few days’ residence in a flat organised by the Soviet embassy, Trotsky received visitors from the West, who rented the Izzet Pasha place on Büyükada. He had, of course, to promise not to interfere in Turkish politics, but it seems that quite a close watch was kept over him. The gardener reported to police intelligence as to his visitors.

It is also clear from a recent Russian biography, Edvard Radzinsky’s, that Stalin received copies of everything Trotsky wrote. In fact, he became jealous of the breadth of Trotsky’s interests. The house was on the sea, and fish became Trotsky’s hobby – he even wrote a monograph on a particular one, the rockfish, deep red in colour and with fins of a vaguely hammer-and-sickle shape (it was given the name Sebastes leninii). In 1942, Stalin took time off from the Second World War and contributed an article on this creature to the Zoologicheski Zhurnal.

Now, how did Stalin get hold of Trotsky’s correspondence? It can only have been through a deal with the Turks, their side of the bargain involving the garment factory, but we do not quite know.

There have been romantic films about Trotsky on Büyükada, including one about his eldest daughter, Zina. Trotsky was not a good father – irascible, uninterested, didactic. All his children came to a bad end (it is interesting to note that the children of senior Communists often do seem to have turned out badly, whereas, for whatever reason, those of senior Nazis did surprisingly well). He had made a romantic and very early marriage which did not survive his first period of exile under the Tsar. One daughter died of tuberculosis. The other, Zina, turned up on Büyükada, already seriously neurotic. After nine months, her father packed her off to a Berlin psychoanalyst, but that did not do the trick: she killed herself. Trotsky’s younger son, from his second marriage, repudiated his father altogether, and tried to make his life as a natural scientist (Stalin had him killed, as he did other, even remote, connections of Trotsky’s, including his long-divorced first wife). The elder son, Lyova, managed Trotsky’s relations with the German Left, fled Hitler in 1933, and established himself for a time in Paris, where he died after an operation in hospital – perhaps the work of Stalin’s henchmen, as was rumoured at the time, though officially denied. Trotsky wrote an obituary, blaming himself for his tyrannical ways with the young man.

Eventually, all that was left of his family was an infant grandson (who is still alive today) and his fussy second wife, Natalya. One grand-daughter survived years and years of orphanages and camps in the Soviet Union. The French Trotskyist Pierre Broué set up a meeting of the two in 1988, but they had no language in common.

Trotsky organised the Büyükada house for his writing, taking over almost the whole of the second floor as an office and creating an enormous table out of bricks and planks. The library filled out (though it caught fire from a defective stove) and there were many, many visitors – including Georges Siménon, then a young Belgian journalist. He found Trotsky reading Céline’s Voyage au bout de la nuit, then regarded as a classic left-wing anti-war book: Céline ended up as a ranting anti-Semitic propagandist on the Vichy radio. There was a little court of devoted admirers – the Frenchman Alfred Rosmer; a Belgian, Jean van Heijenoort, who lectured brilliantly on Gödel and mathematical logic; a German, Otto Schüssler, who proposed to Trotsky the tactic that Trotskyists later used to effect in unsuspecting moderate socialist parties, “entrism” or, as it is now called, “entryism” – the infiltration of disguised Trotskyists for revolutionary purposes.

Trotsky himself was quite guarded as to the interviews he gave, and was severely self-disciplined in his daily routine, visiting Istanbul only once, to see the Aya Sofya. American publishers gave him easily enough to live on, and he used his time to write – every day a long letter or a pamphlet (Salut à l’opposition chilienne, and the like), as well as his volumes on the Revolution, his autobiography, and his attempts to understand why on earth the Bolshevik Revolution had turned out as it did. Why had Stalin won? Trotsky’s answers are not at all satisfactory: Stalin just a bad man, letting a nasty bureaucracy develop – “Genghis Khan with a telephone’.

It is not at all clear that Trotskyism – judged by what the man did – was significantly different from Stalinism: Genghis Khan with a phrase book. Permanent revolution, the supposed war against the cancer of bureaucracy, led straight to Mao’s grotesque Cultural Revolution, and has otherwise caused endless lesser futilities with trade unions and fanciful local governments in Western Europe.

Eventually, Trotsky was able to leave Büyükada – first, in 1932, to address some Danish students at a stadium in Copenhagen; then, in the summer of 1933, to France, where the Radical-Socialist Daladier government was prevailed upon to give him shelter (in various places in the provinces, under a pseudonym, and heavily shadowed). Did Stalin lean on the Turks to make him move on? No evidence: Trotsky himself often complained of remoteness and isolation, and he had, after all, lived for two years in France before the Revolution. But the French expelled him, and he went on to Norway, where there was a left-wing government. Then he became non grata again, but the Mexican Revolution had broken out, and the government there offered him support (through the painter Diego Rivera, with whose wife, Frida Kahlo, Trotsky became obsessed, to the point at which Natalya took offence).

It was there, in August 1940, that Stalin’s murderers caught up with him. Trotsky himself knew Stalin very well, and guessed that the assassins would be on to him: maybe, even, he just did not care any more. Ramón Mercader, a handsome seducer, got into the confidence and the bed of an American Trotskyist woman in the household. Trotsky had a passion for a sort of lollipop called salamadra helada (frozen salamander), made of frozen cactus-pulp covered with milk chocolate and sprinkled with bitter cocoa powder and ground almonds. Mercader managed the twice-weekly delivery of a case of the stuff, and his comings-and-goings passed unnoticed. One day he asked the maestro for a word in private about some aspect of revolutionary analysis. Under his coat was an ice-pick. Mercader put it through Trotsky’s brain.

The photographs illustrating this article are taken from David King’s Trotsky: A Photographic Biography (Basil Blackwood, 1986, now out of print). Other books by David King on the Russian Revolution include The Commissar Vanishes (1997) and Ordinary People (Francis Boutle Books, 2003), which marks the 50th anniversary of Stalin’s death.

The Russian love affair with the Caucasus has been long and cruel, though the outside world knows little of the multitude of ethnic groups who for millennia have inhabited this remote strip of land the size of France.

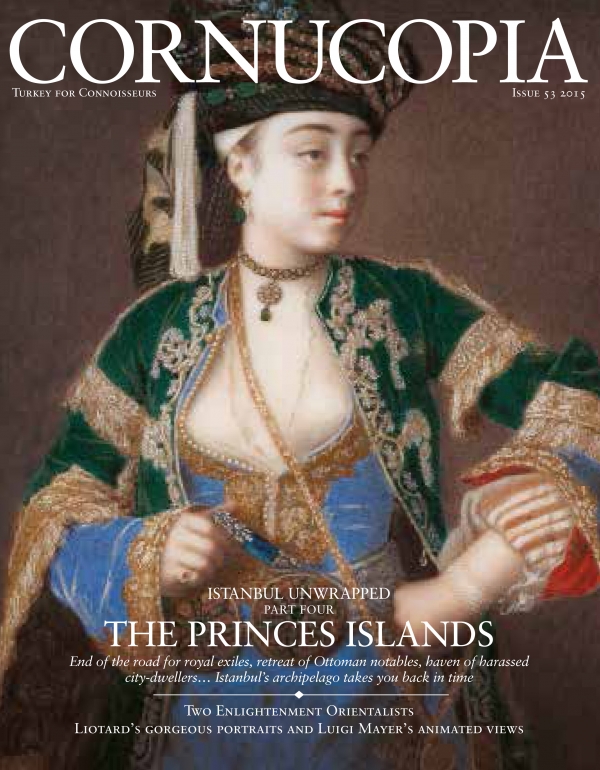

Few cities have been served so faithfully by an artist as Istanbul was served, in its twilight years as a great imperial capital, by Fausto Zonaro. By Philip Mansel

Carrots once came in a broad palette of hues – from white, cream and yellow, through pink and deep red to purple and black – as well as variegated versions of them all. Black carrots from the east of Turkey were famed for their medicinal properties.

More cookery features

Turkey’s Kaçkar Mountains, a daunting extension of the Caucasus high above the Black Sea, are only for the intrepid. Ali Özgü Caneri and Kate Clow took advantage of the short trekking season to scale two of the saw-edged summits. Photographs by Kate Clow.

Turkey’s northeastern neighbour, Georgia, is a fairytale country with a hard edge, and its entrancing landscape of isolated hilltop cathedrals and medieval monasteries just demands to be explored. By Minn Hogg

Built as way-stations for Orthodox pilgrims on their way to the Holy Land or Mount Athos, the rooftop churches of Karaköy are a forgotten corner of the Motherland in the heart of Istanbul. By Owen Matthews. Photographs by Simon Wheeler

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now