Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionIntrigued by the fate of the glorious houses built by Azerbaijan’s first oil barons at the turn of the 20th century, Brigid Keenan and photographer Tim Beddow track down all that remains of those glory days.

There is a building boom in Baku, Azerbaijan, the like of which has possibly not been seen since the dawn of Dubai. At one end of the great Boulevard that follows the curve of the Caspian Sea around Baku bay, they have just finished erecting The Tallest Flagpole in The World, and at the other, a colossal supermarket that looks like some gigantic beached whale is nearing completion; construction has just begun on the new Carpet Museum, shaped like a huge rolled-up rug; dozens of high-rise buildings in ever more extraordinary shapes are growing like fungi on the hillside (one of them, a hotel owned by the President’s wife, is shaped like a flame because Azerbaijan is the land of eternal fires). Zaha Hadid’s Haidar Aliyev Cultural Centre is under construction, and a vast new project, the Globus Plaza, is planned for her in the future. Buildings that look like flying saucers, cigars, globes, rings, you name it, are in the pipeline.

It is all a very far cry from the beautiful city of Baku built by the first oil barons in the brief 40-year period between the discovery and exploitation of oil in the 19th century, and the invasion of Baku by the Bolsheviks in 1920.

Ludwig Nobel, one of the first oil barons (and brother of Alfred, who created the Nobel Prize), described the frenzied, oil-obsessed town of Baku in 1870 as being like the Klondike in the gold rush. By 1900 Azerbaijan supplied more than half the world’s oil, and the successful speculators – the oil barons, as they came to be known – became the new aristocrats, vying with one another to create the most spectacular and extravagant houses in the capital – the houses have their owners’ initials, sometimes their names, carved into the façades like designer labels. It is said that one super-competitive chap actually built a house in solid gold; another, the self-taught oil engineer Murtuza Mukhtarov, built an enormous Gothic palace for his wife as a Valentine’s Day surprise – she had admired a building in Europe when they were travelling together, and he secretly commissioned a copy of it for her back home.

Baku had been an Oriental city but now everything European became the craze: European-style architecture – and quite often European architects, designers, artists, stucco-, metal-, stone- and wood-workers; there were jobs for them all in Baku. Hundreds of new buildings were constructed in those years, every one decorated with hand carving, or painting, or marquetry, parquet, gilding, and so on. Whole streets of these houses, built in the local golden stone, made – still make – parts of Baku look like Paris. The building frenzy then must have felt much as it does now.

Some of the oil barons – the Nobels, the Rothschilds – were foreigners, but most were locals and there are wonderful rags-to-riches stories, the best one being the tale of Haj Zeynalabdin Taghiyev. Taghiyev, the illiterate son of peasants, scrimped and saved and, with partners, invested in a piece of land hoping to find oil. They found nothing and the partners pulled out – but then came a small earthquake and suddenly oil gushed from Taghiyev’s land. Overnight he became one of the richest men in the world. Like many of the other oil barons of those times, Taghiyev not only built himself a fabulous palace, but he used his fortune for good, creating schools, public buildings, and a whole fresh-water system for Baku with a reservoir outside the town and pipes and canals and pumps to bring water to the city.

Those first oil barons were civic-minded: oil tankers were obliged to bring soil back to Baku from fertile Lenkaran in the south – the Baku soil was poor – so that gardens and parks could be created for the people. The Nobel family, whose house was a few kilometres outside Baku in what was known as the Black City (Baku itself was the White City), built a theatre (and formed a small orchestra to play there), as well as a school and a hospital for their workers.

All of these were burned to the ground by the 11th Red Army when the Soviets stormed into Baku in 1920. The Nobels escaped with their lives, but many oil barons did not – Mukhtarov, he of the surprise Valentine’s gift, shot the soldiers who rode into his palace on horseback, but then turned the gun on himself. Every house was commandeered, and no “capitalist” was allowed to stay. Even Taghiyev’s good works counted for nothing; he and his family were thrown out of their glittering palace – in which gifts from European nobility mingled with those from the Emir of Bukhara – with only the clothes on their backs.

The Soviets turned some of the most spectacular of the barons’ houses into institutions: part of Taghiyev’s house became a museum; the ornate and beautiful house that the Rothschilds built for their manager became Baku’s National Art Gallery (though for a while it was the offices of the new Soviet party leaders). The beautiful house once owned by the folk-singer-cum-oil-millionaire Mir-Babayev became the headquarters of the nationalised oil industry – today it is the offices of the State Oil Company. The house that was the Valentine’s gift became the Wedding Palace, where couples celebrated their union. The marvellously painted home of Agha Bala Guliyev, the Flour King of Baku, became the Architects’ Union, the girls’ school that Taghiyev built became the Institute of Manuscripts, and the Muslim Philanthropic Society, modelled on the Doge’s Palace in Venice and built by Naghiyev, the richest baron of them all, in memory of his son, became the Academy of Sciences (it was rebuilt after a fire, and the new building has Soviet stars instead of Koranic calligraphy).

Buildings not imposing enough to be turned into institutions got short shrift in the 70 years of Soviet rule: they were divided up into small apartments, their decoration destroyed, their creators and their history forgotten.

Now, nearly two decades since the fall of the Soviet Union, the Baku–Ceyhan pipeline supplies the West with oil, and the city is booming and once again proud of its oil barons.

But they don’t like “old” in prosperous modern Baku. Even in the Old City, a small area of town which surrounds the old ruler’s palace and is a Unesco World Heritage site, houses have been demolished to make way for a Four Seasons Hotel, and many others have been refaced in new or “compo” stone. This is a favourite trick in Baku, where restoration seems to mean making everything new again. When Taghiyev’s house underwent a massive restoration recently, even the front door was replaced by an identical new one. I watched as, for no apparent reason, the stone carvings were sliced off the outside of my favourite house in the town and replaced with new carving.

The worst example of this refacing idea is happening right now to the famous girls’ school just outside the Old City (where Nino studied in the great love story Ali and Nino) – the whole façade has been removed and is being replaced with an entirely new one in a different design. It will look nice, but it will not be the original. Similarly, the stone arches of the old arcade in the town known as the Art Alley have just been knocked down and replaced with new ones. (The clean-up does not apply round the backs or inside the buildings, which are often in a shocking state. It really is façadism.) Aside from renewing façades, there is a positive fever for restoring the institutions housed in the wonderfully decorated oil barons’ houses – anything worn or old, anything with character, has to go. Right now the Wedding House is closed for restoration, as are the Architects’ Union, the National Art Gallery and the Institute of Manuscripts. In the meantime the lesser oil barons’ houses, the ones that were not turned into institutions, are sorely neglected or, worse, being pulled down.

The old stone houses along one whole side of the pleasant Molokan Gardens square in the centre of town have recently disappeared, and a kilometre-long block behind the Haidar Aliyev Concert Hall is currently being demolished to make way for a colossal new development. Most of the disappearing houses in this particular area are small and insignificant, but the neighbourhood used to have a nice feeling and there is one important oil baron’s house that, according to the locals, is to be pulled down with the rest. It is the Melikov house, built in 1910 and described as a valuable architectural monument by Shamil Fatullayev, whose book on the old houses, The Architectural Encyclopedia of Baku, is a bible for anyone interested in this city.

Meanwhile, in pretty Mamadaliyev Street (right behind the demolished side of the Molokan Gardens), there is a row of important oil-baron houses which also feature in the Encyclopedia, the bestknown of which has four rather podgy Atlas figures holding up its balconies. Next door to it is the charming house that used to be the Georgian embassy – ominously, all these houses are empty and in a parlous state. It seems clear that they are being allowed to fall down so that a large development can take place on the site.

At this rate, Baku is soon going to look very modern and clean and shiny and perfect, like a Disney World version of itself, and future generations will have lost all that was old and genuine. I asked Mr Fatullayev what he thought of the changes that have taken place in the town since he catalogued and described it so meticulously only just over ten years ago. “It hurts me,” he said. “I try to tell people what is happening, but it makes no difference.”

Another Azerbaijani commented: “In the first oil boom the barons built the most beautiful city of Baku; in the second oil boom they are destroying it.”

But then again perhaps this is exactly the kind of thing people in Baku said 130 years ago when those first oil millionaires began replacing ancient Azerbaijani buildings with their new Parisian pastiches.

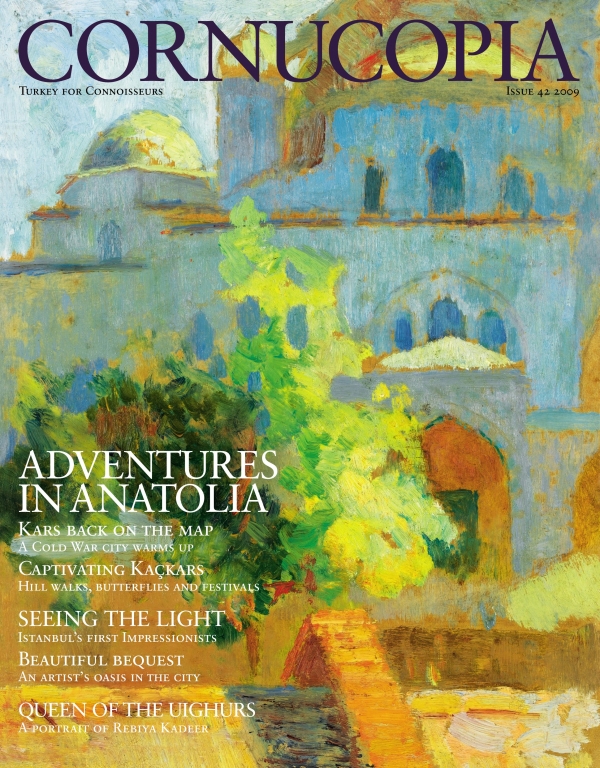

For the fully illustrated article, order Cornucopia 45

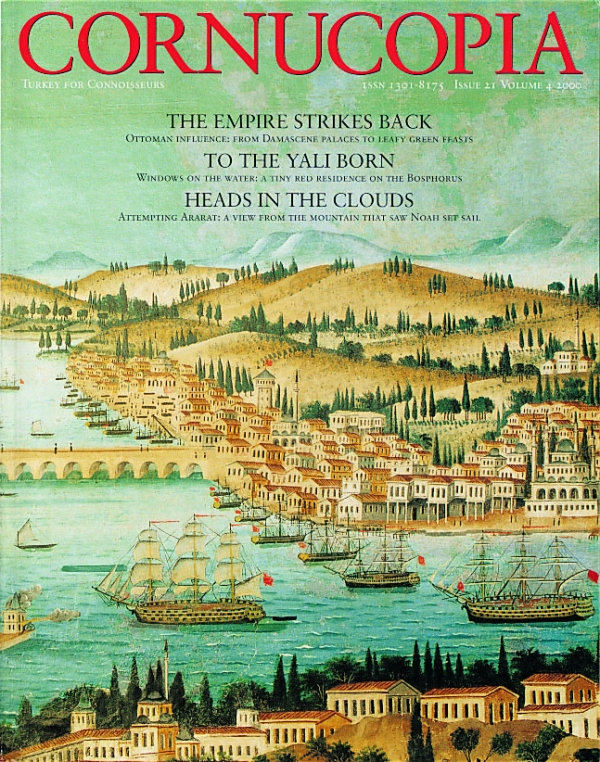

Further reading: ‘Azerbaijan International’ magazine at [www.azer.com]. This prize-winning magazine, edited by Betty Blair, comes out two or three times a year and covers every aspect of Azerbaijan, including the architecture ‘Azerbaijan with Excursions to Georgia’, new edition, by Mark Elliott, £14.99. [www.trailblazer-guides.com] Brigid Keenan is the author of Damascus: Hidden Treasures of the Old City, with photographs by Tim Beddow (Thames & Hudson, £35), which was featured in [Cornucopia 21] (/issues/ottoman-damascus/)

John Frederick Lewis (1804–76), was the supreme orientalist, fêted for his sumptuous Ottoman scenes. The secret of his success, says Briony Llewellyn, lies in the vivid sketches he made during his time in the East

The İzbeli family have owned a country konak south of Kastamonu since the 17th century. Today the house, with its magnificent barns, is one of the best-preserved Ottoman country houses in Turkey

The jewel in Kastamonu’s crown is a mosque in Kasaba, a tiny village with a flock or two of sheep, guarded by shepherdesses, in a sea of wheat fields. Built in 1366, the Mosque of Mahmut Bey is a brilliant relic of the golden age of the Anatolian beyliks, the warring principalities that flourished when the great Byzantine and Seljuk empires were in decline

At London’s inaugural Wines of Turkey jamboree, Kevin Gould hears how the country’s winemakers are cultivating a taste for their distinctive products

Strawberries growing in the wild are gems of mouth-watering delight that bear little relation to the showy, insipid-tasting fruit on supermarket shelves. But there are still good garden strawberries to be found. Berrin Torolsan encourages us to seek out locally grown, seasonal fruit bursting with fragrance. Her simple recipes celebrate the best of berries

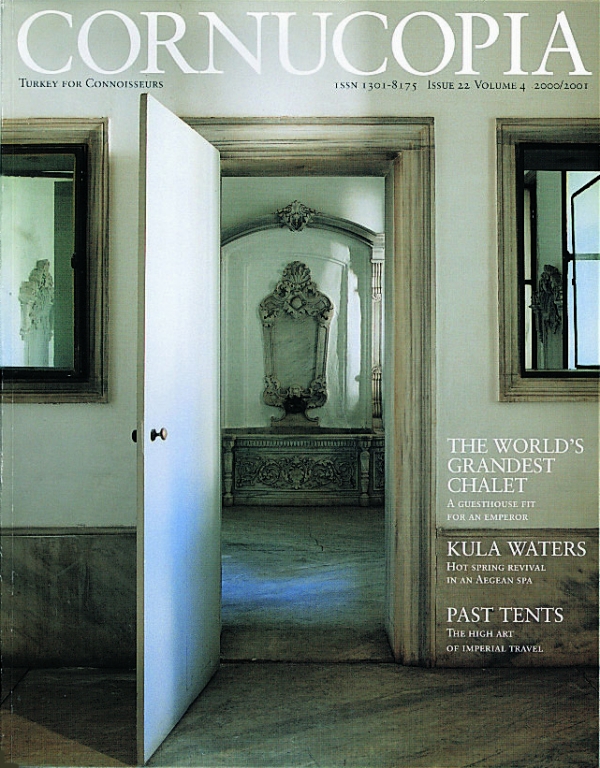

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now