Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

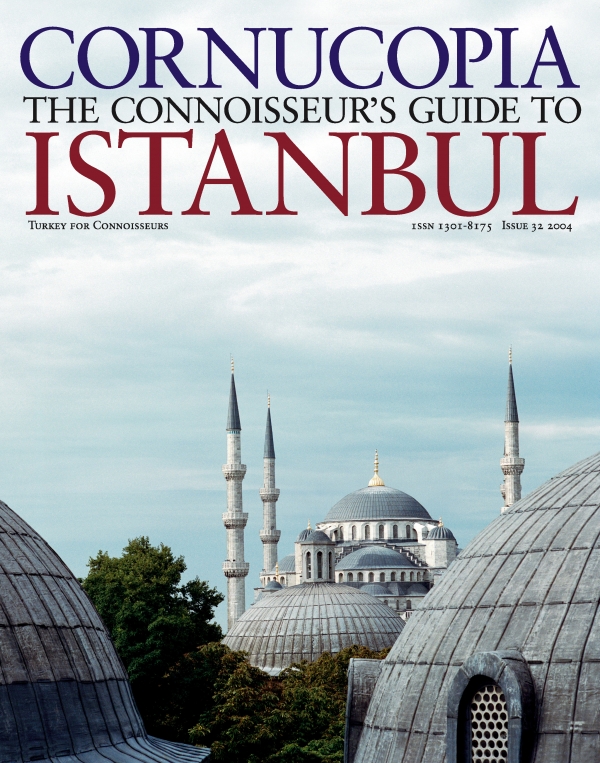

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionAfter the grim years of the early 1920s, Turkey experienced a brief period of euphoria. A new Republic was born, and new faces appeared in this land of hope, among them the brilliant but now forgotten photographer Othmar Pferschy (1898–1984), who turned up on the Orient Express in 1926 and stayed for 40 years. In 2005 his daughter Astrid von Schell donated his archives to Istanbul Modern, who staged his first-ever retrospective. Cornucopia has selected some of his most poetic images. Norman Stone examines why it was that so many Central Europeans were drawn to Turkey.

Central Europeans were heavily involved in Ottoman affairs from the very start to the very finish of the empire. It was a Hungarian, one Urban, who constructed the enormous gun that blew the fatal breach in the walls of Constantinople in 1453 and let the Turks in.

By a strange twist, Hungarians were also in at the end of the empire. Turkish nationalists, wishing to emancipate themselves from the corrupt and cosmopolitan Ottomans, partly took as their model Hungarian nationalists such as Count Paul Teleky, who were similarly trying to escape from imperial corruption and cosmopolitanism, in their case that of the Habsburgs. Such Hungarians composed the first version of the Republic’s anthem, and even had some influence on the version of Latin letters that the Turks used when they changed the alphabet, the sounds being remarkably similar (the Turkish ‘c’ is the Hungarian ‘gy’, or English ‘dj’).

After the First World War, Turkey was the only one of the defeated powers to strike back against a dictated peace treaty, and she gained much admiration for that.

The process of state-building then got under way, with formula that had already been applied all over central Europe.

It was this world that Othmar Pferschy both reflects and records. He was even born at the very moment – 1898 – when ‘modernism’ or Robert Hughes’s ‘Shock of the New’, started off… Film and photography were very much part of the progressive world.

Young Pferschy cast about for something to do after the First World War, became an apprentice photographer in Vienna and in Germany for a couple of years, and in 1926 betook himself to Istanbul. Quite a number of enterprising Central Europeans did so as the world settled down in the post-war period – the great German Ottomanist Franz Babinger worked for Lloyd in Istanbul, and another great German Orientalist, Helmut Ritter, had to leave Hamburg because of a homosexual scandal (and, given the time and place, the action must have been considerable) and became the librarian of Istanbul University, meanwhile paying his bills by performing in a string quartet.

But going to Turkey at that time was not as exotic as it might appear: Turks were on the map, as far as taking part in the Olympic Games or Boys Scouts were concerned, and their literature was also recognised (‘The Fisherman of Halicarnassus’ was well and truly on the best-seller lists). When young Pferschy travelled on the Orient Express to Istanbul he went for purely professional reasons, simply to photograph an interesting country at an interesting time…

Born near Graz in Austria, Pferschy lived in Istanbul from 1926 to 1969, with only a brief interlude during the Second World War. When he returned to the city from Berlin after the war with his Istanbul-born wife and children, he opened his own studio.

The photographs in this article are from Under the Light of the Republic, held at Istanbul Modern, May 2006

Kevin Gould waxes lyrical over Château Musar, a legendary wine from the old Ottoman Levant, and salutes the brave new Turkish winemakers who stay true to their roots.

We were greatly saddened to learn of the death of one of the great archaeologists of the 20th century, James Mellaart, whose discovery of Çatalhüyük in the 1950s fundamentally altered our understanding of the past. In 2005, on his eightieth birthday, he talked to Christian Tyler. We publish the article here in full, and at the same time offer Jimmie’s family our utmost sympathy.

Some like their asparagus translucently white, others prefer crunchy and green. Whatever your choice, it takes lightness of touch to reveal the delicate flavour.

You embarked in Paris or Vienna and alighted at Sirkeci station, an Oriental fantasy in the shadow of the Topkapı Palace. This was the train that brought Istanbul into the heart of modern Europe: the fabled Orient Express.

Cappdocia, ‘Land of the Beautiful Horse’, was once famous for the fine steeds that bore its valiant knights. Few horses are left, but they can still transport you into another world. The photographer Jürgen Frank captures the eerie magic of the Anatolian plateau, Susan Wirth is exhilarated by five days in the saddle and David Barchard guides us through the epic landscape.

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now