Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionThere are some excellent Silk Road exhibits in this museum, which is one of the largest and most engaging in China, with some 40,000 artefacts and labelling in English. Ethnographic material comes from the Uighur peoples, with some handsome textiles, while archaeological finds are from lost desert cities. Most famously it has preserved mummies of Caucasians found in the Tarim Basin in the Taklamakan Desert. Dating from between 1,500 and 4,000 years ago, they are well preserved thanks to the dry conditions, as are some of their clothes: the 3,000-year-old ‘Cherchen Man’, perhaps a shepherd, was found dressed in a red twill tunic and tartan leggings, which some experts say is similar to cloth woven in Europe at the time.

Our flight from Istanbul to Gaziantep entailed a 4.30am start, and remains an uneventful haze, with dim recollections of something musically folklorish meeting us on the Tarmac, and several of our party getting on the wrong coach, having failed to recognise their fellow travellers. Once en route, Haluk – a Tatar by birth, an angel by nature and our Marlon Brando lookalike guide for the expedition – gently explained that we would do well to stick to tea and soup for the next few days as our delicate digestive systems would never cope with Turkish cuisine. How we laughed and resolved to ignore his advice.

Everywhere there are roses at the roadside and low bushy trees of pistachio nut, a speciality of the region, but my strongest impression is that every man in these parts must either be a lorry driver, a garage owner or a motor mechanic. Sometimes there are six repair workshops in a row in the middle of nowhere.

Just as the scorching sun reaches its zenith, we arrive at Belk›s, or Zeugma. Personally I feel too hot and sleep-deprived to appreciate the full significance of what is here, or since we are beside an artificial lake behind a dam on the Euphrates, what is no longer visible, either having been submerged beneath the rising water or remaining unexcavated beneath the soil. It is said that this archaeological site of massive importance was only discovered when the dam was under construction in the Nineties, but later it turns out the myriad Greek and Roman villas dating from 3000 BC, with their sophisticated mosaic pavements and wall paintings, have been well known to thieves and smugglers for centuries. The lake and its chalky bed is turquoise, and its indented coastline forms many a delightful cove with groves of pistachios and deep red poppies, which makes it just the place to build a villa. Thankfully we cool off in the coach and stop for a perfect lunch of grilled Euphrates trout served in a shady garden. Then to the archaeological museum in Gaziantep. Here teams of young restorers work with patience, chisels and dentist’s drills cleaning and repairing dozens of mosaic pavements removed to safety from Zeugma. Most memorable is the heart-rending portrait of a gipsy girl with tousled hair and accusing eyes.

The steepness of the museum’s wheelchair ramp and a jolly blue cart selling every conceivable variety of roasted nut result in mirth and greed reserved only for the very, very tired – not that our day is in any way finished. On we speed to visit the restoration of a private house dating from 1815 in Gaziantep’s Armenian and Jewish district, now an ethnographic museum. Rooms surrounding a cool galleried courtyard are wood-panelled and painted in correctly high-gloss creams and duck-egg blues, with some coloured glass panes in the fanlights and internal windows. Bed rolls billow from storage shelves, their Ottoman stripes reflecting gaily in the shiny paintwork. Catacomb cellars far below are so cool that a block of ice will keep going all summer.

To the Tuğcan Hotel at last, where I get waylaid in the foyer by a mini-bazaar selling local craft products. Bales of beautiful silky corded moiré cloth, in every combination of stripe imaginable and at a derisory price, are not to be missed.

Dinner is in the woods a few miles out of town. Kartaltepe restaurant is a circular garden pavilion with tables radiating out from it like spokes in a cartwheel. The spread to which we are treated is lavish: the table top is obliterated by dishes of fresh-peeled walnuts, soft white cheeses, salads, dips, relishes, sauces, breads – and these were only the starters. In our party, we have a Hollywood star, AMcG, and media attention is gathering momentum, not all of it welcome to her or to any of us. There are mutterings.

Day Two Outside the hotel there is yet more media presence, not for our film star this time, but for our American banker, EM, who resembles the Turkish finance minister Dervi so greatly that a reporter from CNN is accosting passers-by and filming their response to her question “Who is this man?” Beaming, they express great pride in the curious impression that the minister has grown six inches since eating Gaziantep food. We bus off towards Nemrut Dağı, 7,000 feet (2,300m) up. With a chilly climb ahead, we are armed with socks, stout shoes and sweaters. A flattish plain gives way to rocky outcrops. There are farm villages and drystone walls, the green cornfields are peppered with oaks, mulberries, pistachios and other low trees. Bare trunks of vine are trained up two-storey houses before bursting into leaf, forming canopies of shade over the flat roofs. Even modern block-built houses follow the tradition of Turkish construction by having wooden courses at each floor and at their corners to frame the structure.

I am impressed with the importance of recording how country people live, build, farm, eat and dress wherever one is. These aspects are the quickest to change for ever, polluted by television and mechanisation. I wish we could pause to see inside a farm before its owners discover the internet and e-mail.

The countryside begins to look vast and grandiose, with rivers and rocks and in the distance noble mountains. Ball-shaped gum arabic pines join oaks amid barley and cotton rippling in the breeze. Kindling is stacked in the fields either around a tree trunk or high off the ground in the branches, like giant bird’s nests. Hay cut by women is hand-spun into thick ropes, twisted into skeins like knitting wool and stacked to dry out on rooftops. Pinks and white hollyhocks edge the fields and stork’s nests crown every pole and pylon…

Day Three

For anyone launching a religion and wanting it to get off to a flying start, Şanlıurfa is the place: it is drenched in worship – every religion from first to last emerged from this province. Back in 9000 BC their idols were bulls, ducks, lions, wolves and snakes. By 2000 BC the animals had given way to sun, moon and planet gods. And when the people heard of Jesus of Nazareth’s teachings, they did not hesitate to embrace Christianity…

Day Four

“The drive to Mardin will take about 45 minutes,” our optimistic guide, Haluk, informs us. “Turkish minutes”, he adds. Two hours later we skirt the edge of old Mardin, built on a hillside so steep that every façade of every house is visible. Most buildings are of beautifully cut and carved stone with a Crusaderish look. Our destination is further on, past a couple of military outposts at Darülzaferan Monastery, which was once a thriving Syrian Christian Orthodox establishment but is now reduced to a couple of priests, Fathers Gabriel and Abraham. They have two students and a few schoolboy pupils, but the situation seems a precarious one. Father Gabriel, probably in his fifties, wears long black robes and a curious black bonnet embroidered in white. He makes a small, knowing figure with darting eyes…

Day Five

The worry about Hasankeyf is that it is on the Tigris at a point where, if a proposed dam is built, it, and 180 surrounding villages, will be flooded and 10,000 years of history lost. “Is there a future for subaqua archaeology?” wonders Haluk.

Naturally the population are resisting relocation as best they can, but their voices are countered by strong economic arguments in favour of the dam project. The ethical debate has been taken up internationally and I am thankful not to be the arbiter of such a heart-breaking dispute.

At Hasankeyf, the Tigris, which has meandered through our journey here, becomes one of the most beautiful rivers I have ever seen. On the far bank, a tall sandstone cliff rises up, its face hewn with cave dwellings and flights of steps zigzagging to the top, where a grassy plateau is layered with buildings and ruins from every civilisation. The Tigris, which is no longer in full spate in late May, has beaches and islands where locals are splashing in its blue waters, or picnicking under makeshift awnings on the shallow-sloped sands.

We stop to take a closer look at a small mausoleum to Zeyn el-Abdin, idylically set in a field running down to the river. All around are vines and scarlet-flowering pomegranate bushes, while the little pointy dome is fuzzy with grasses that have seeded there. It is an Eden in which to spend eternity.

Crossing a modern bridge into the city affords a splendid view of the original Roman one some way upstream. A few of its hefty piers still stand firm against the current, and we learn that once the central arches were connected by a wooden drawbridge, raised occasionally to exclude marauding armies…

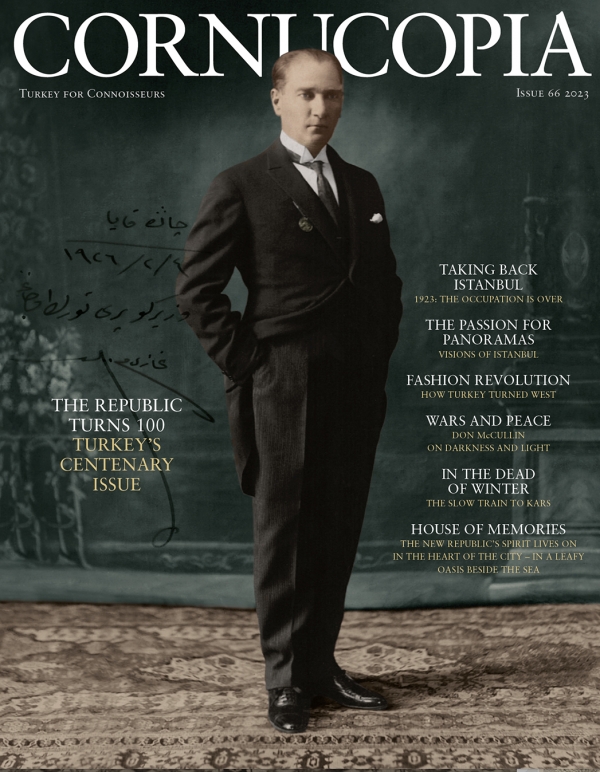

Mustafa Kemal, father of modern Turkey, was invited to a reception at the German embassy, where he congratulated the excavator of the Hittite capital of Bogazkoy on recovering the remains of his people’s ancestors. The German archaeologist was just about to protest when a kick from his ambassador changed his reply to a simple: ‘Yes, Your Excellency.’

Atatürk was not being naive, writes Richard Frye, author of the anecdote and one of the thirty-four Turkish, Russian and Anglophone scholars who have contributed to this magnificent book. The Hittites were just as surely ancestors of modern Turks as were the Turkic nomads who began moving into Anatolia after the first millennium. see The Battle of Manzikert

What is a Turk? The title of this tome (it weighs nearly three kilos) has been carefully chosen. For its central hypothesis is that the question cannot be answered, except with propagandist falsehoods, and is therefore largely useless. As a contributor notes, the name “Türk” itself appeared only in the sixth century AD, and then in Chinese documents.

Turkish nationalism - the idea that there is a pure ethnic type or a pure Turkish language - is an even more recent invention: the ideology developed in the nineteenth century and the claim to a territorial empire (pan-Turkism) only in the twentieth. Ergun Çagatay, the Time/Life photographer whose marvellous pictures engendered this project, became convinced after ten years spent travelling in Central Asia that the adjective ‘Turkic’ was not only synthetic, but actually divisive. Nationalist zeal already had a sour taste for him: he had spent months in hospital with severe burns after being caught in an Armenian terrorist attack at Orly airport in July, 1983.

Yet there are 135 million people who speak a Turkic language. What is so striking - almost as if to confound the multi-ethnic thesis – is the unity of those languages, and the similarity of the peoples’ character and customs in spite of the enormous distances which separate them, from Yakutia in eastern Siberia to the Balkans, see Cornucopia Issue 30 The Turks of Thrace and Iraq see Cornucopia Issue 29 Kirkuk, to Frankfurt and London’s Finsbury Park.

The scholar Talat Tekin identifies a dozen Turkic linguistic groups, most of them mutually intelligible to a high degree. Only four - Chuvash, Yakut, Tuva and Khakas - are mutually incomprehensible, even to each other. Co-editor Dogan Kuban observes that the Turkish word bir (one), is the same from Turfan to Istanbul, while Western Europe has many variants: one, ein and un. There are common character traits, too, says Cagatay, possibly derived from a common nomadic past: Turkic speakers tend to be reserved, suspicious, quick to anger, but resilient. Even their body language is similar. They also share, even in Muslim communities, a respect for the equality of women.

Mention of Islam reminds us that most Turkic speakers are Sunni Muslims. Yet there are shamanists too, Buddhists, Christians and even – in the Karaim of Lithuania – Jews. Religion can cut both ways. Where Islam enjoys political power it can become regressive and intolerant; but where it does not it helps preserve the people’s cultural identity (rather as Catholicism did in Soviet-controlled Poland).

This book, then, is a supranational history of symbiotic relationships, cultural mergers and collisions created by nomadic Turks who emerged from the Siberian-Mongolian borders and were, in the words of one writer, ‘probably the most dynamic agents of world history’. It describes the mutual impact on the Chinese, Persians, Slavs, Arabs and Greek Byzantines. A separate chapter is devoted to the Turco-Mongol connection, see Cornucopia Issue 37 Genghis Khan where we are reminded that the Moghul emperors of India were actually Turks; and two chapters relate the fascinating story of the Tatars and the Volga Bulgars before and after their defeat in 1552 by Ivan the Terrible.

If it is proper to see the Turks as an unavoidably hyphenated people, like Afro-Americans or Anglo-Indians, it is simpler to understand them in two broad categories – nomad or sedentary, see Neal Ascherson’s Black Sea mountain people or valley dwellers - rather than struggle with the myriad names they have used over time. Naming and classifying can have paradoxical consequences. The Soviets’ artificial division of central Asians into five “nationalities” created animosity between them after the fall of the USSR. The same has happened in western China.

This book is not all hard work. There are some delightful excursions. Chapters on cuisine, for instance, prove that the view from the kitchen is historically very helpful. We learn also that the infant Genghiz Khan was reared on wild fruit, wild onions and lily-root porridge, and there are recipes; see A Soup for the Qan, including one for ‘Noah’s Pudding’. Other subjects covered include epic poetry, the Kazkh yurt, arts, crafts and architecture. There is not, however, much on music; see Cornucopia Music

The contributors have achieved what the blockbuster exhibition, Turks, at the Royal Academy in London three years ago, see Cornucopia Issue 33 - magnificent though it was - could not do. They have traced and explained the cultural loans and debts of the nomadic phenomenon. The scholarly differences between authors are instructive (who were the Magyars? Were the Huns Turks?). And if their contributions sometimes overlap, that is no bad thing in a topic so complex.

As for the pictures, they are a feast for the eye, pages on which the reader can rest from poring over the (rather too small) print of the text. We see not only ‘ethnic’ pictures of Askhabad’s desert market or the old game of boskashi (a mounted struggle for the carcass of a goat) see Cornucopia Issue 36 Sykes in Turkestan, but stunning shots of people, objects and buildings, some of them since destroyed.

The world depicted here is vanishing, of course. The destruction that totalitarianism began, globalisation unfortunately seems set to continue. But then destruction has always been part of the nomad story. This book should not only excite anyone interested in the history of Eurasia; it should help mobilise support for the preservation of a vibrant non-European culture.’

A few years ago, eastern Anatolia acquired a piece of living archaeology in the newly built village of Ulu Pamir. To find it, drive northwards from the town of Van and turn off after eighty kilometres or so and you come to this Kirghiz village, whose inhabitants are a calling-card from the Turkic past. They are not just Kirghiz, from far away in Central Asia, on the Chinese border. They represent the Kirghiz way of life as it was before the Soviet Union all but extinguished it in the 1920s and 1930s.

The village was named Ulu Pamir, meaning Great Pamir, because the Kirghiz inhabited the Pamir mountain ranges of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Kazakhstan. Nowadays, these former Soviet republics are independent states, but three generations of sovietisation reduced the Kirghiz culture there to little more than folklore. That is why musicologists and other people in search of authentic Kirghiz culture as it used to be descend on Turkey’s Kirghiz village.

For the Turks and Kurds around Ulu Pamir, the Kirghiz must be as distinctive as are the Amish to the ordinary citizens of Pennsylvania. Women of obviously Asiatic origin shop in the small towns of the area dressed in traditional Kirghiz red skirts. But the villagers have no difficulty speaking good Anatolian Turkish. By a strange twist of migration dating back hundreds of years, Kirghiz is linguistically closer to Anatolian Turkish than are other Turkic languages, such as Kazakh or Uzbek, spoken in countries geographically nearer to Turkey.

Issue 66, December 2023

Turkey’s Centenary Issue

Issue 66, December 2023

Turkey’s Centenary Issue

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now