Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

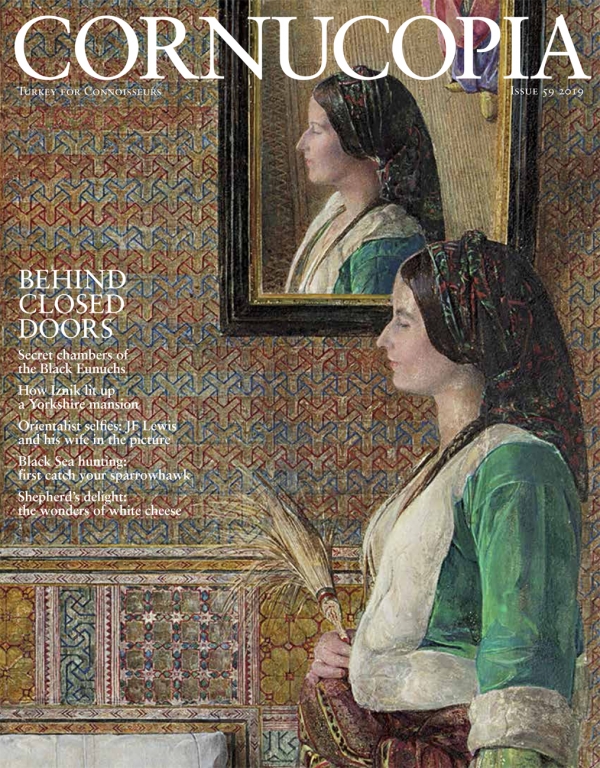

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionBriony Llewellyn and Charles Newton on a rediscovered portrait by JF Lewis

In October 1840, the Scottish artist Sir David Wilkie wrote from Istanbul to his brother Thomas, “We have encountered John Lewis – from Greece and Smyrna. He is making numbers of drawings.”

The English painter John Frederick Lewis RA (1804–76) is most admired for his meticulously detailed Orientalist scenes, with brilliant effects of light and shade, glowing colours and exotically clothed women in light-filled Ottoman interiors (see Cornucopia 59). Portraits by him are rare (other than covert self-portraits in Eastern garb), and this fine study of an eminent Ottoman general, painted c1841, came to light only in 2022, having descended through a branch of Lewis’s family. It was last on the market in 1895 and was otherwise known only from being exhibited at Wass’s Gallery, Bond Street, in 1851, and at the Royal Scottish Academy two years later.

The name “Yochmas”, as Lewis probably spelt it, is indecipherable in the inscription; the legible words are “General” and “Constantinople”, proof enough, along with the costume, that this is the portrait of August Giacomo Jochmus that Lewis is known to have painted.

Jochmus cuts a distinguished figure in the ornate uniform of an Ottoman general. In Lewis’s gouache and watercolour portrait, he is recognisable as the same man portrayed in a more ostentatious oil painting by Carl, Prince of Wied, in 1849 (right).

Jochmus is remembered primarily for his role as chief of staff of the Ottoman forces in the conflict culminating in the 1840 naval Siege of Acre. Yet the general was remarkable for taking part in several other tumultuous events in Europe.

Born in Hamburg, he seemed destined for trade, but instead embarked on military studies in Paris. At the age of 19 he joined the Greek War of Independence, and by 1828 he was aide-de-camp to the commander-in-chief of the Greek army, General Sir Richard Church. In 1832 he was employed in the Greek Ministry of War. Dissension within the new Greek government eventually caused him to leave for England in 1835. There, on the recommendation of Admiral Edmund Lyons, British minister at Athens, he joined the British Auxiliary Legion, recruited to support Queen Isabella II of Spain’s progressive Liberals against the conservative Carlists supporting her uncle, the pretender Carlos de Borbón. After two years Jochmus was promoted to brigadier-general.

He returned to England in 1838, only to be sent to Istanbul to prepare for the looming war in Syria. There he was appointed Ottoman chief of staff of the Anglo–Austrian–Turkish Army with the prized honorific of Pasha of Two Horse Tails, the second-highest rank of general (the Sultan had four).

Under the 1840 Convention of London, which aimed to bring peace to the Levant, Kavalalı Mehmed Ali Pasha, the self-proclaimed Khedive of Egypt and Sudan, was obliged to return the Ottoman Empire’s Syrian provinces ceded to him in 1833. His army, led by his son Ibrahim Pasha, resisted, counting in vain on French support. The Oriental Crisis, as it was known in the West, had the makings of a far wider conflict, but the British and the Ottomans and their allies were soon victorious. The Ottoman fleet, which had earlier defected to the Egyptians, was blockaded in Alexandria, and the port of Acre (Akko, now in Israel), Ibrahim’s last stronghold, was besieged, bombarded and captured in November 1840.

During the negotiated retreat of the Egyptians, the Ottoman government, wanting Ibrahim’s army destroyed, ordered Jochmus to attack, which he was more than willing to do. Lord Ponsonby, the ambassador to Turkey, supported the action, but was opposed by Commodore Sir Charles Napier, who had led the landings. When the prime minister, Lord Palmerston, intervened on Napier’s side, it sparked a war of words. Both Jochmus and Napier were to publish their own opposing versions of events.

Jochmus remained in Istanbul as a senior commander in the Ottoman army until 1848, when revolution in Germany prompted his return there. On March 17, 1849, he was appointed minister of foreign and naval affairs of the new German Empire, a short-lived attempt at unification. After its dissolution Jochmus travelled through Europe, Egypt, Arabia, India, China and America. In 1859 the Austrian Emperor gave him the title Freiherr von Cotignola. In 1866 he was appointed field marshal but saw no action. He returned to private life, a polyglot whose collected writings, August von Jochmus' gesammelte schriften, published in 1883, included texts in polished English prose indistinguishable from that of contemporary British statesmen.

It is not recorded exactly how Lewis met Jochmus. Like Wilkie, Lewis was probably based in Pera, the European and Levantine quarter. He seldom undertook portrait commissions, but while he was in Istanbul, in 1840–41, he painted another important foreign resident, the British envoy Lord Ponsonby**, a controversial figure, whose good looks had saved him in Paris when the mob decided he was “un trop joli garçon pour être pendu” (“too pretty a boy to be lynched”).* The connection with Jochmus’s patron may have led to Lewis’s portrait of the general.

An additional factor may have been the portrait by Wilkie of Admiral Sir Baldwin Wake Walker. The admiral, too, had been seconded by the British, joining the Ottoman navy in 1838 to become effectively its commander-in-chief, known as Walker Bey, later Yaver Pasha, for his role in the Siege of Acre. Lewis’s portrait of Jochmus may be seen as the military counterpart to Wilkie’s portrait of the British naval hero.

The presence of two celebrated artists in the city at the same time prompted the popular British journal The Art-Union to observe: “Sir David Wilkie is still at Constantinople; John Lewis is there also: they are no doubt doing that which the Pacha of Egypt could not do, and will make a good ‘division of the Turkish empire’ between them.”

The portrait of Jochmus by Lewis was given by the artist’s widow, Marian, as a wedding present in 1903 to Edward Sinclair Gooch, grandson of Lewis’s sister, Ann, and her husband, the Rev Charles Stonhouse, rector of Frimley in Surrey, where Lewis is buried. Gooch himself was fatally wounded in Gallipoli in 1915.

NOTES

*The story of Lord Ponsonby's escape from lynching in Paris is given in The History of Parliament Online]. Wikipedia suggests that it was a mob of women that saved him.

** There are two versions of JF Lewis's portrait of Lord Ponsonby, c1841, when he was ambassador to the Sublime Porte. One, illustrated in this article, is in the Ömer M Koç Collection. The other is in the UK Government Art Collection, and currently hangs in the British Embassy in Vienna.

The birds are flocking back to İzmir’s Gediz Delta

Off the beaten track in Anatolia with Don McCullin

Istanbul, newly distilled in cool monochrome: the photographs of Annette Louise Solakoğlu

Once the staple food of nomads and warriors, pastırma has turned into a gourmet delicacy. Text and photographs by Berrin Torolsan

In the cave cellars of Cappadocia, Udo Hirsch and Hacer Özkaya are reinventing ancient ways with wine.

A must for stylish travellers, the Ottoman document case carried state secrets as well as intimate messages. A show of these covetable objects at the Sadberk Hanım Museum captivates Philip Mansel

Nick Thorpe pays tribute to a friend and the much-loved author of Cornucopia’s ‘Letter from Anatolia’

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now