Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionVisitors to 1830s Istanbul were astonished to hear the strains of Rossini and Donizetti performed by Ottoman bands. As Emre Aracı reveals, Western music was the passion of Mahmud II

An intriguing letter arrived at the Paris offices of the French music journal Le Ménestrel in the autumn of 1836, with an exotic provenance: Constantinople. Addressed to the editor, it was from a “faithful subscriber” who signed himself simply “Ed. de V…”; in all likelihood he was a member of the Christian community of Pera.

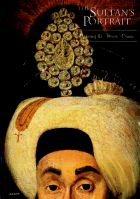

“In Constantinople the ancient Turkish music dies in agony,” he proclaimed. To this revelation he added: “Sultan Mahmoud loves Italian music and has introduced it in his armies. This is only one of his reforms; the brother of Donizetti is the director of his music, and since they do not have much music, they always play one particular work, called the March of the Sultan, which is said to have been composed by him. He particularly loves the piano so much so that he ordered many instruments from Vienna for his ladies. I do not know how they are going to learn to play, since no one is permitted to approach them.”

The editor of Le Ménestrel was further astounded by the news that Mahmoud, who for some time had been composing music himself, was contemplating sending his manuscripts to the French journal for possible publication. Unfortunately, there is no evidence of the royal manuscripts arriving in Paris, but musical links between Turkey and France at the time seem to have been strong, for in the same year we come across references to a group of sixty Parisian musicians being requested to perform in Istanbul at the wedding ceremony of one of the daughters of the sultan. The English Musical Gazette of June 10, 1836, informed its readers of this event, albeit rather scathingly: “The Sultan Mahomet [sic] has commanded the engagement of sixty musicians from Paris, who are to proceed to Constantinople for the purpose of performing at the approaching nuptials of the Sultana. ‘Assuredly (says a French paper), the good city of Constantinople will reach the height of our civilization’. Ha! Ha! because sixty Paris fiddlers are going there! If conceit and stink are to form the standard of civility, Paris will long remain paramount.”

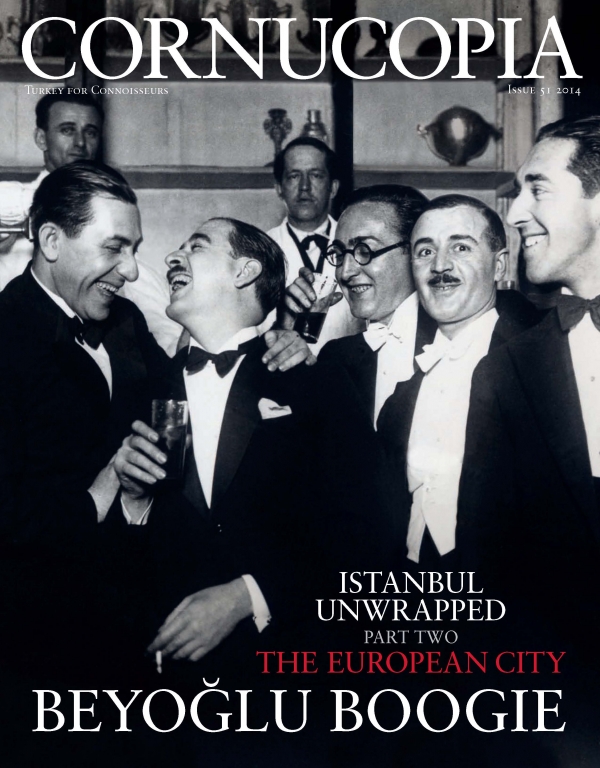

“European civilization” was certainly the buzzword of the reformer sultan and his entourage, who had given up their baggy trousers and turbans for tight frock coats and the fez, the new official headgear for bureaucrats, officers and soldiers of the empire. Unsurprisingly, in the spirit of reform that followed the dismemberment of the Janissaries in 1826, with their mehter bands, the musical palette of the emerging Ottoman élite gradually began to acquire a taste for musique européens.

The sultan himself seems to have taken a personal interest in the encouragement and infusion of this tradition into the social fabric of his court and newly created army, known as the Asakir-i Mensure-i Muhammediye. Thus the centuries-old bands of the Janissaries had to give way to a European-style military band under the direction of an Italian: Giuseppe Donizetti (1788-1856), who was later created a pasha. It is therefore not surprising to find travellers to the Levant experiencing the shock of hearing the music of Rossini or Donizetti performed by Turkish youths on the banks of the Bosphorus, against a perfect backdrop of newly painted villas – just as Byron, 30 years earlier, had anticipated in Don Juan, describing it as “a pretty opera-scene”.

A British naval officer, Adolphus Slade, witnessed and recorded the early achievements of Donizetti’s modest band during one of many visits to the city in the 1830s: “The strains of a military band, and, unexpected treat to me on the banks of the Bosphorus, we heard Rossini’s music, executed in a manner very creditable to Professor Signor Donizetti. We rose and went down to the palace quay, on which the band was playing. I was surprised at the youth of the performers… and still more surprised on finding that they were the royal pages, thus instructed for the Sultan’s amusement. Their aptitude in learning, which Donizetti informed me would have been remarkable even in Italy, showed that the Turks are naturally musical.” (Sir Adolphus Slade, Records of Travels in Turkey, Greece etc, and of a cruise in the Black Sea with Capitan Pasha in the years 1829, 1830 and 1831.)

Mahmud’s passion for European music was shared by his successor, Abdülmecid, host to many travelling virtuosos of the period who came to perform at his palace – the most illustrious being Franz Liszt, in 1847. Despite ill health and the humiliating defeat of his armies by the rebellious governor of Egypt, Mehmed Ali, Mahmud continued his musical reforms until his final days.

Ironically, the last musical performance at his court was perhaps one of the first examples of a new generation of Turkish musicians, who could play major works from the classical European repertoire, as reported in the Musical World of 6 June 1839: “Where will the march of mind and music stop? The gods have made his Sublimity, Mahmoud, musical and in return he has determined to infuse his tastes into his harem. With this view he has recently given a concert to the fair ones, at which a young Turk, who had acquired his education at Paris, played among other pieces one of Beethoven’s sonatas with variations, which enraptured the assembly and drew down thunders of applause.” Sultan Mahmud died a few weeks after this concert, at the age of 54.

High in the Toros Mountains, Chris Gardener finds the remote Kasnak Forest carpeted with peonies in spring. Photographs by Kate Clow

The Russian artist Ivan Aivazovsky may have been derided by the avant-garde, but his dreamy seascapes and atmospheric panoramas won him patrons in high places. Ivan Samarine rediscovers a 19th-century virtuoso

The world’s grandest chalet was built by Abdülhamid II for the visit of Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1889 and was a powerhouse of political activity in the final years of the empire. Today the house in the grounds of Yıldız Palace, on a hill in Istanbul, is all but forgotten. Philip Mansel treads softly through its silent halls. Photographs by Fritz von der Schulenburg

To save its fine architecture, a volcanologist has come up with a plan: to turn Kula into an elegant spa town by tapping its plentiful thermal springs. By Roger Williams. Photographs by Jean Marie del Moral and Roger Williams

Three köftes still stand out in my memory. Just thinking of them makes my taste buds ache. The first was in my early childhood: freshly grilled cizbiz kofte, a round patty the size of a flattened walnut, so named because it makes a delicious ‘jiz-biz’ sizzling sound as it cooks…

More cookery features

The London Academy of Ottoman Court Music, with Emre Aracı. Produced by Ates Orga,

The London Academy of Ottoman Court Music, with Emre Aracı. Produced by Ates Orga,

Prague Symphony Orchestra, directed by Emre Aracı, produced by Ateş Orga

The London Academy of Ottoman Court Music, with Emre Araci

The Prague Symphony Chamber Orchestra with Cihat Askin, violin. Directed by Emre Araci and produced by Ateş Orga

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now