Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

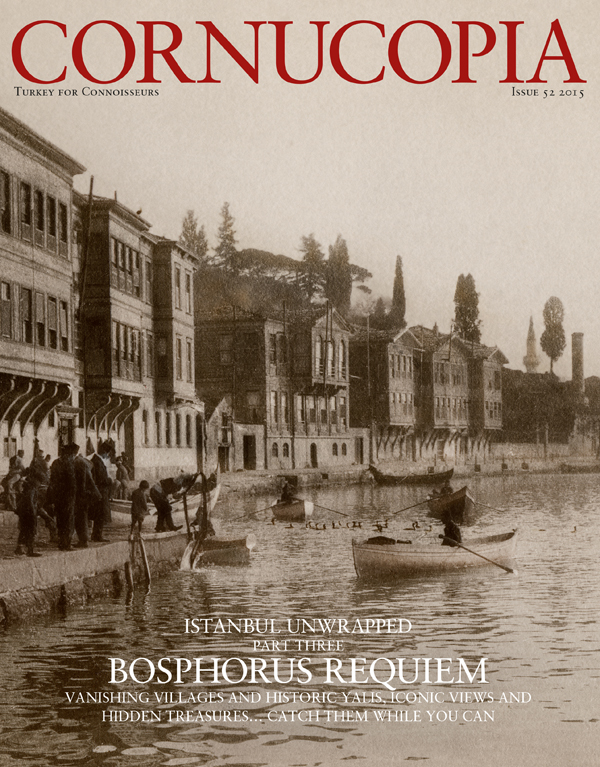

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionIn the years 1914–18, Istanbul’s population shrank by a half. Crippled by occupation and the relocation of the capital to Ankara, the city had changed from one of the world’s greatest imperial metropolises to a crumbling and forgotten city not far from the Greek border. The well-known cliché of the city as a bridge between continents rang false – this was a city on a fault line, a hangover from the complexities of the Ottoman Empire that did not quite fit into the clean modernist lines of Atatürk’s republic. The President himself would not even revisit the city until 1927. In the words of the early Republican publication La Turquie Kémaliste, the best thing for a visitor wanting to understand the contemporary country to do was to “take the first train to Ankara”.

That the interwar period was a dark and uneasy one in Istanbul is often forgotten. The sweeping reforms undertaken by Atatürk took time to stick, and moving the capital had spelt economic catastrophe for many of the city’s inhabitants, in particular the bureaucrats of the ancien régime, who were left out of the Gazi’s brave new world.

Three recent books have this period of Istanbul’s history in their sights, each in a slightly different way drawing on its astonishing richness and complexity. The end of the Great War had ushered in an atmosphere of fervid excitement across Europe, and Istanbul was no stranger to the drastic changes to urban life this entailed. Yet in Istanbul the joys of peace were tempered by the instability and anxieties of the time. This was a world far away from the cosmopolitanism so loved by the city’s eulogists.

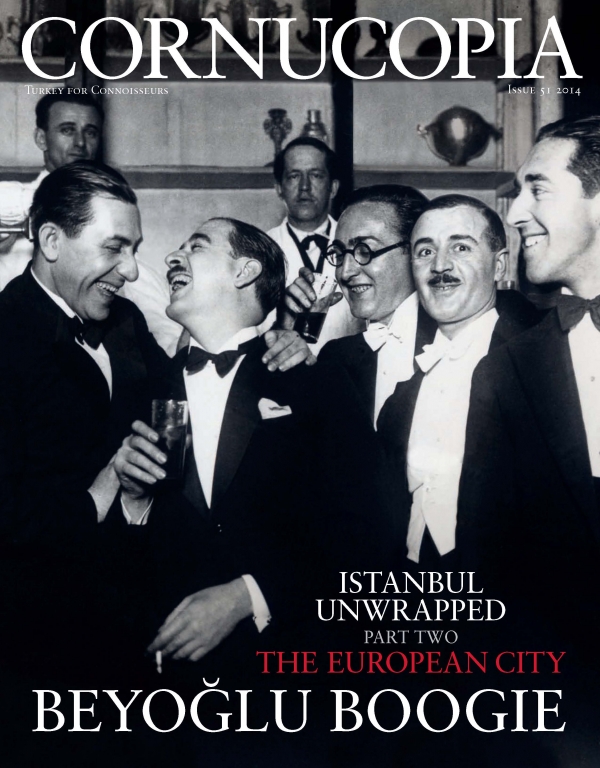

Vladimir Alexandrov’s masterly The Black Russian tells the astonishing story of Frederick Bruce Thomas, an African-American nightclub impresario who made his way from his birthplace in Mississippi to antebellum Moscow, before fleeing the Soviets with the tide of White Russians who ended up in Istanbul in 1919. Alexandrov follows his subject in forensic detail and, in so doing, sheds a great deal of light on the plight of many of the Russians who made the city their home. Thomas was a dab hand at creating nightclubs, but his Istanbul chapter makes for sad reading. Establishment after establishment folded and even after experiencing some success with his club Maxim, chased out of Istanbul by his debtors, he ended up in the still-provincial capital of Ankara, destitute, imprisoned for bad debts.

Thomas had always been a curious feature in accounts of the city in the period, often credited with bringing jazz to the city – a claim that is certainly overstated. Yet the White Russian influx of which he was a part did have an important and lasting impact on the city in meeting the increasing need, both from soldiers garrisoned there and from the local population, for jazz music. Raucous accounts of Thomas’s clubs, with their bands of African-American musicians and polyglot audiences, fill Alexandrov’s book: “the gaiety, the din of the Jazz band, the dazzling luxury, the women amidst beautifully appointed tables decorated with flowers and crystal”.

In Istanbul, as elsewhere, jazz emerged as the music of the destitute, picked up by the wealthy keen to slum it. For the motley crew of artists and musicians thrown up by the post-war tide in Istanbul this was certainly the case. The excellent and timely Midnight at the Pera Palace, by Charles King, goes for a wider view, offering a fascinating take on the period and the characters that passed through the city. Each chapter explores a theme or a specific story, in chronological order, telling many of the best-known tales of the period (several of which have been told in the pages of Cornucopia) – those of Trotsky, Nâzım Hikmet, Halide Edip Adıvar and Pope John XXIII – as well as more surprising accounts of such figures as the first Turkish Miss World. Each presents us with an alluring snapshot of a lost city, “the principal storm centre for Europe and Asia”, with its beauty pageants and spies, exiles and music-makers. King is at his best when the narrative moves beyond Istanbul and ties the city into the wider context of the interwar world – rebetiko in Athens and New York; the arrival of the Russians; the complex and contorted games of espionage that shocked the city. Yet the somewhat anecdotal nature of the chapters can occasionally hinder this bigger picture, even as they give the book a playful and delicate charm. In particular, the story of the American scholar and archaeologist Thomas Whittemore, in all his well-connected and eccentric glory, is elegantly told.King’s eccentric and alluring characters, such as Whittemore and Frederick Thomas, paint a vivid picture of the interwar years in Istanbul, but the clientele of the Pera Palace and the habitués of Maxim give us just one perspective of the city’s story.

A third, less recent book, Playships of the World: The Naval Diaries of Admiral Dan Gallery, 1920–1924, while maintaining a similar perspective, crystallises some of the issues thrown up by writing on this period. Dan Gallery was a young naval officer when his ship, the USS Pittsburgh, docked in the Bosphorus in November 1922, as part of the occupying forces. His tales of high jinks in the seedy bars of Pera/Beyoğlu and his amorous affairs with local girls make for fun and revealing reading: “Maxim’s was navy headquarters ashore and an old navy party was thrown there. No one else had a chance in there. We had a goat on hand, got the score by quarters, gave all the yells, took possession of the orchestra and played Anchors Aweigh, got gloriously drunk, smashed up the furniture, had snake dances, and celebrated the occasion with all due ceremonies.” Yet each night Gallery returns to his warship. While we relish his fun, Gallery, like so many of the foreigners in Istanbul, almost oblivious of the torments of its population, strolled around the city as part of an occupying force. From Waugh to Scott Fitzgerald, the bright figures of excess in 1920s Europe and America juxtapose themselves with the darkening clouds of poverty and unrest. The same was true in Istanbul. The Great Depression deepened the decline brought on by the occupation and the moving of the capital. And the bright stories of nightclubs and beauty pageants were the exceptions, not the rule. For all the glitz and glamour, underlying these three books is the story of a great city dethroned, in crisis.

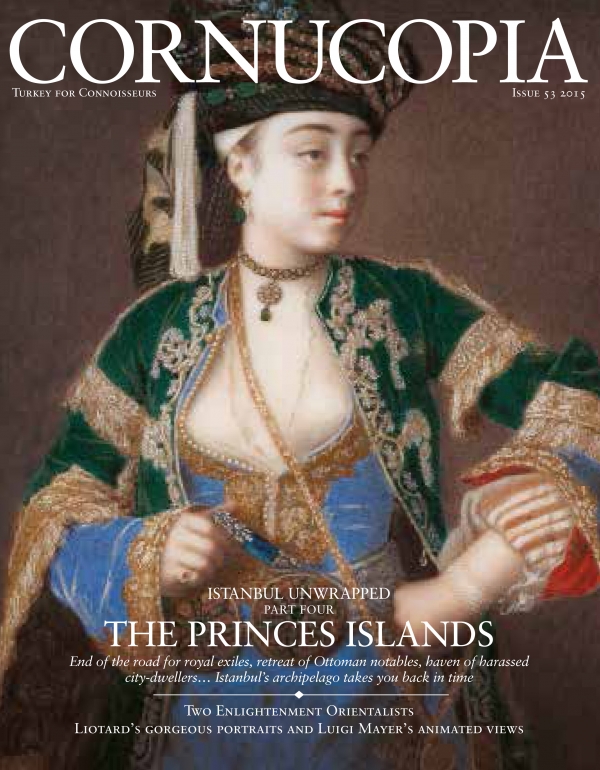

Luigi Mayer made his mark with lively, quirky scenes for the British ambassador to Constantinople, painting viziers and villagers, soldiers and servants across the Ottoman Empire. He deserves to be plucked from obscurity, argues Briony Llewellyn

London’s luminous Liotards, prayers on a shirt, bare truths in Beyoğlu, and a Biennial all at sea… Plus three lost Anatolian empires and their intrepid champions

The 18th-century Swiss portrait artist Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702–1789) is widely regarded as the first Orientalist. The four years he spent in Turkey from 1738, drawing and painting Western merchants and diplomats as well as Ottoman citizens, made him the first serious European artist to find his subject matter in the East.

Few statesmen of the turbulent last years of the Ottoman Empire can have held more illustrious titles – at a less auspicious time – than the diminutive Küçük Said Pasha. David Barchard looks back over the eventful and chequered career of a man of many parts.

Owen Matthews introduces our portrait of the Princes Islands, from busy Büyükada, via pretty Heybeliada, one-hill Burgaz and arid Kinaliada, to the haunting, deserted Yassıada

Besides being quite delicious, the simple broad bean is nothing short of a little bundle of magic. Rich in minerals and vitamins, it contains the chemical L-dopa, which feeds dopamine and adrenaline to the brain and body.

Since he became enchanted by the ‘Big Island’ 15 years ago, Owen Matthews has enjoyed its seasonal changes and watched its popularity grow – not least among soap-opera fans

Heybeliada is more compact and less showy than Büyükada, but just as fair

Three groundbreaking archaeological exhibitions shine a spotlight on great Anatolian empires and their champions. Istanbul showcases John Garstang’s illuminating work on the Hittites. Berlin celebrates the work of Friedrich Sarre, who brought the Seljuks to life. And treasures from the Phrygia of King Midas head for Philadelphia

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now