Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

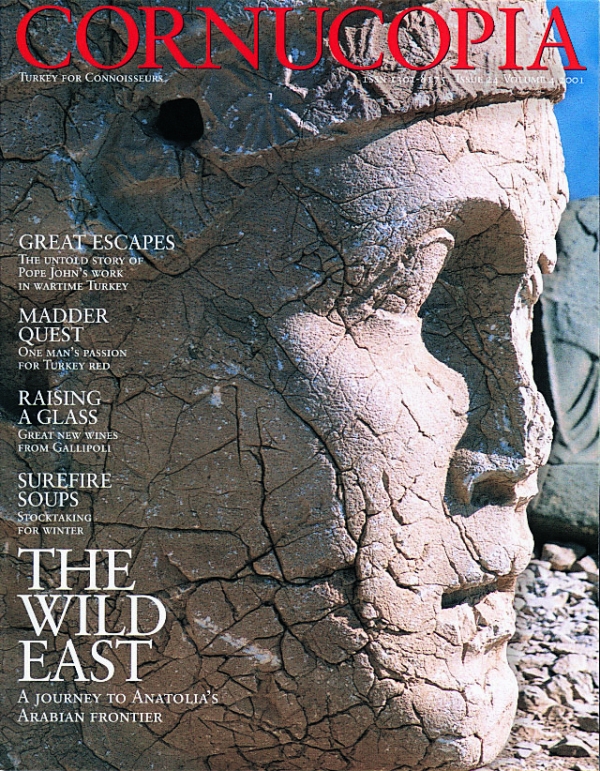

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionIn the remote hills of the Upper Euphrates stands a masterpiece of Islamic art whose entrances are a riot of medieval sculpture. The Great Mosque and Hospital of Divriği – the only single building in Turkey to which Unesco has given World Heritage status – was built in the 13th century and is now in precarious condition. Cemal Emden captures its glory in photographs, Patricia Daunt marvels at its extravagant beauty, and Daniel Shaffer tells the story of the mosque’s unique carpets

NOT A PLACE FOR THOSE IN A HURRY

Reassuringly inaccessible, Divriği has always taken time to reach – and its riches time to savour. Patricia Daunt on the historical figures who made the journey

Articles, I read once, work best if facts are kept on short rations. Rationed they seem to have been on the early-thirteenth-century Great Mosque and Hospital at Divriği, one of the great masterpieces of Islamic architecture. Few of the traveller-scholars crossing Asia Minor to record architectural wonders visited the remote Ulu Cami and Şifahane, set on a hill above the town. Recognised in 1987 as a World Heritage site – the only designated individual building among Turkey’s nine sites – its flamboyant and sophisticated originality more than justifies this belated accolade.

Within the triangle of Sivas, Malatya and Erzincan, modern maps show Divriği easily accessible by road and rail. Do not be misled. It takes time to reach this small mining town, centre of Turkey’s principal source of iron ore. Though it is set in the midst of a congregation of prosperous central Anatolian towns, even during the heyday of the great Seljuk Empire, when trade was flowing in all directions, Divriği was remote, and withdrawn from the sultan’s court at Konya.

Overlooked by the forbidding Demir Dağı (Iron Mountain), hidden among the troughs and gorges of the Çaltı Çayı – unregulated tributary of the young Euphrates, carrying white waters to the Keban Dam – Divriği stands on the valley floor, skirted by willows and poplars and flanked by steep hills rising in a stark confusion of copper-green, sand-yellow and blue-grey. In a bare and unpopulated land where outcrops of limestone are snow-white and springs as clear as crystal taste of iron, it is not unusual for the severe continental winters to cut Divriği off from the outside world for weeks at a time…

METHOD IN THE MADNESS

Yolande Crowe finds logic in the profucion of styles and symbols

Almost 800 years ago, in 1228–29, the Great Mosque of Digriği was constructed as a single building on the hillside overlooking what was then a vibrant city…

THE HOUSE OF MENGUJEK… AND THE ARTISTS WHO CREATED DİVRİĞI

By Oya Pancaroğlu

One of the handful of Türkmen dynasties to establish themselves in Anatolia in the wake of the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the Mengujekids appear to have their origins in the military elite of the Great Seljuk Empire. Not much is known of the dyasty’s mysterious eponymous founder, Mengucek Ghazi, probably a former general who took possession of the region of the upper Euphrates valley around the year 1080. His descendants continued to rule in the cities of Erzincan, Kemah and Divriği through the 12th century, at a time when the balance of power was constantly shifting between multiple political entities of post-Manzikert Anatolia, including the Danishmenids, the Seljuks and the Saltukids, as well as the Byzantines and the Armenians of Cilicia.

In the highly variable circumstances of the 12th century, the Mengujekids managed to hold on to these territories, though they eventually yielded to the ancient Turkic custom of power-sharing among members of the ruling family. Thus, from the middle of the 12th century, Erzincan and Kemah came to be ruled by one branch of the Mengujekid family, which rose to relative prominence, while Divriği was ruled by another…

MEET THE ANCESTORS by Daniel Shaffer

Few places can have more resonance in the story of the Turkish knotted-pile carpet (halı) than the Great Mosque and adjoining hospital in the remote Anatolian hill town of Divriği. Today a World Heritage site, the building of this complex was begun in 1228–29 by the Mengujek Emir Ahmet Shah, a client of the Seljuk Empire in Konya.

Thanks to the Islamic tradition of vakf (pious donation), from its earliest days through to the last third the twentieth century, the Great Mosque, or Ulu Cami, served as a remarkable repository, a true treasure house, for some of the most inspirational surviving early Anatolian carpets, and for diverse carpets from far beyond.

The Divriği carpets, some of unsurpassed interest and beauty, extend across well over half a millennium. In addition to Turkish rugs, the collection includes significant pieces from the Caucasus, northwest Persia and Syria. The carpets first came to the attention of scholars and connoisseurs in the early 1960s, when they were seen, not long before his death, by the patron of Turkish carpet studies, Professor Kurt Erdmann of Istanbul University, and his protégé Şerare Yetkin, who illustrated a handful of them in Türk Halı Sanatı, the 1974 Turkish first edition of her ubiquitous Historical Turkish Carpets (Istanbul 1981)…

When eaten raw as a salad, turnips are shredded or thinly sliced like radishes. Their distinctive mustardy bite, which cleanses the palate, makes them excellent company for rich meats and fish. Cooking however, transforms the starch in the turnip, giving it a mellow taste.

More cookery features

The city of Dresden is now home to one of the finest displays of Turkish art and armoury

Little known and rarely visited, the hauntingly beautiful sanctuary of Zeus at Labraunda – built by the family of the legendary Mausolus high above Milas – was for centuries Aegean Turkey’s most revered shrine. A Swedish team has managed to uncover the ruins without sacrificing the serenity of these sacred hills.

Daniel Shaffer explains the value of the Great Mosque of Divriği’s ancient carpets.

Reassuringly inaccessible, Divriği has always taken time to reach – and its riches time to savour. Patricia Daunt on the historical figures who made the journey

Famous for his atmospheric films set in stark landscapes, Nuri Bilge Ceylan is now attracting attention with his photography. Maureen Freely leafs through the pages of a fine limited-edition album of his enigmatic, painterly scenes

In September 2009, six travellers set out on horseback to retrace the early part of the route taken in 1671 by the Ottoman traveller Evliya Çelebi on his way to Mecca.

Spirited impressions of Ottoman Istanbul in the 16th century from a mischievous Danish artist and an acerbic Flemish envoy.

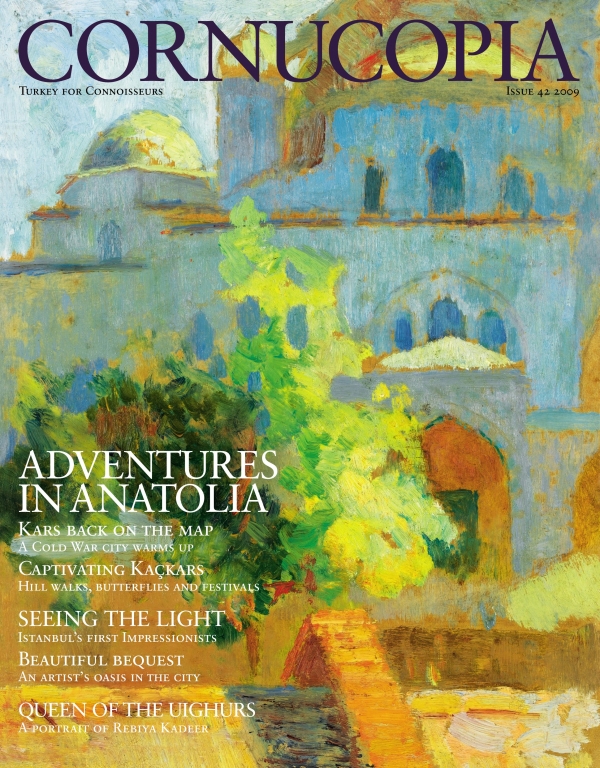

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now