Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital Edition

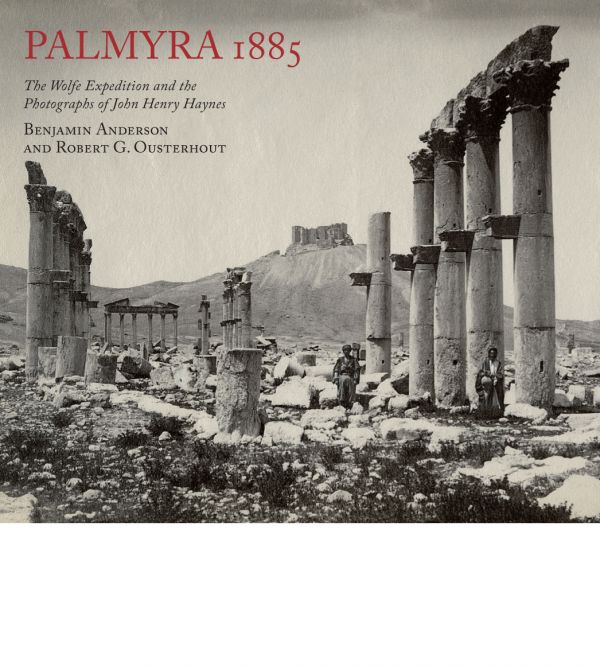

The Wolfe Expedition and the Photographs of John Henry Haynes

Published in October 2016, this is a sequel to Robert G. Ousterhout’s landmark study on the photographer John Henry Haynes in 2011, which has also now been reprinted in a new edition with additional unpublished photographs. Lavishly illustrated with 85 colour plates, including some 80 images that have never before been published, this extraordinary portrait of Palmyra is co-authored by Robert Ousterhout and Benjamin Anderson.

Home to the legendary Queen Zenobia, the Syrian oasis of Palmyra – known as ‘the Pearl of the Desert’ – was one of the most important cultural centres of the ancient world. A key stop on the Silk Road, it was a vital link between the East and the West, and a prize fought over by successive conquering armies.

European adventurers began exploring Palmyra’s priceless Roman ruins in the 17th century, but it wasn’t until the advent of photography in the 19th century that the public became aware of its scale and majesty. In 1885, the sight of Palmyra astounded members of the Wolfe Expedition as they journeyed home from Mesopotamia. The group’s photographer, John Henry Haynes, documented the monumental temples, tombs and colonnades in more than a hundred invaluable images.

Since then, Haynes and his work have largely been forgotten, and the forces of the self-styled Islamic State have destroyed the key monuments of this world-renowned site, including the glorious Temple of Bel. Haynes’s images of Palmyra – published here for the first time – are all the more poignant.

PALMYRA 1885, by Benjamin Anderson and Robert G. Ousterhout, is the first published record of the five fruitful days that Haynes spent in Syria’s ancient desert city.

CORNUCOPIA READER’S COMMENT ‘[Palmyra 1885] nearly made me weep – for the stamina of those older archaeologists (even if they were young people) – for the beauty of the site, for the grandeur of the ancient city, and of course for the loss of the monuments. I wondered if it would include a photo of the site today, but in fact am glad it did not. It made the book more a beautiful and nostalgic record, and less a polemic tract, however discreetly presented. The publication is worthy of the subject. Bravo to Cornucopia, and to the authors for the witty but never flippant text. I hope they printed a lot of copies, as this belongs in any library with anything about the ancient world.’ – Nancy P. Sevcenko, President, International Center of Medieval Art, New York

FROM THE BYRN MAWR CLASSICAL REVIEW…

…As in the case of Ousterhout’s earlier volume on Haynes, the images are beautifully reproduced on high-quality paper, but a hardbound version of both texts would have been welcome. This reviewer might have preferred a larger plan of the site on the inner flap of the front cover in place of Haynes’s 1876 yearbook photograph, but that is a minor quibble. In sum, by calling attention to John Henry Haynes’s sojourn at Palmyra in April of 1885, the authors have done a real service to those interested in the past and future of this important site, as well as to students of the history of American archaeology and archaeological photography. – Pau Kimball, Bilkent University, on the BMCR blog: BMCR 2017.07.25

ON AMAZON.COM…

This fine book chronicles the five days the Wolfe Expedition spent in the fascinating Syrian Desert city of Palmyra. It includes a splendid assortment of photographs by John Henry Haynes. Because the book is printed on high-quality paper and in a large format (approximately 10” x 9”), the antique photographs of the ruins are remarkably clear and quite beautiful. The book is well-organized and the text is both detailed and interesting to read. Amazon Customer Review

IN THE CORNELL CHRONICLE…

This October, Benjamin Anderson, assistant professor in history of art, published his new book “PALMYRA 1885: The Wolfe Expedition and the Photographs of John Henry Haynes” with colleague Robert Ousterhout, professor in history of art at the University of Pennsylvania. The co-authored volume features 80 never-before-published images of Palmyra captured by John Henry Haynes, an archaeological photographer who was a member of the Wolfe Expedition.

That expedition, which journeyed across the Ottoman Empire to Mesopotamia, caught sight of Palmyra while returning home in 1885, giving Haynes the opportunity to capture the cultural center’s majestic temples, tombs and colonnades. “Haynes’s photographs, taken long before Palmyra became a tourist destination, are priceless records of the relationship between a small Syrian community and the remains of the ancient city,” Anderson said. “Many of the views are unexpectedly intimate: for example we see women doing the wash beneath the enclosure of the Temple of Bel, or the expedition settling down for lunch beside the Temple of Baalshamin.”

The book is the first published record of Haynes’ time spent in the ancient city, and the images included were digitized by Anderson in a project funded by the 2015 Arts & Sciences Grants Program for Digital Collections.

Agnes Shin, A&S Communications, October 28, 2016 (see full news item)

Robert G. Ousterhout.

John Henry Haynes: A Photographer and Archaeologist in the Ottoman Empire 1881-1900. Second Edition.

Cornucopia Books, 2016. 152 pages, with 128 black & white photographs.

Softcover.

ISBN 978-605-83080-0-8.

Benjamin Anderson and Robert G. Ousterhout.

Palmyra 1885: The Wolfe Expedition and the Photographs of John Henry Haynes.

Cornucopia Books, 2016.

128 pages, with 85 black & white photographs.

Softcover.

ISBN 978-0-9565948-7-7.

Two recent publications pay homage to John Henry Haynes (1849–1910), American archaeologist and long unacknowledged pioneer of archaeological photography. The first, John Henry Haynes: A Photographer and Archaeologist in the Ottoman Empire 1881–1900, authored by Robert G Ousterhout, is a monograph on Haynes that was first published in 2011. The revised and expanded 2016 edition includes additional, hitherto unpublished photographs. In meticulous detail the study maps out the career of Haynes from his first experiences as excavation photographer in the Assos Expedition in western Anatolia (1881–83) to his years as the excavation director at the Nippur Expedition in Iraq between the 1893 and 1896 seasons.

In the second study on Haynes, entitled Palmyra 1885, Robert G Ousterhout is joined by Benjamin Anderson as co-author. The book focuses particularly on Haynes’ five-day visit to Palmyra carried out as part of the Wolfe Expedition, a survey trip to Mesopotamia organized by the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) in 1885. The study provides a comprehensive account on Haynes’ life and career, as well as a historical assessment of the site itself, with particular reference to its renditions in scholarly and travel narratives, and its documentation in early photography. The two publications are unique in bringing into light John Henry Haynes as a significant figure in the formation of archaeological photography.

These are the first scholarly studies that provide a comprehensive account of Haynes’ career as photographer. The majority of Haynes’ surviving photographs, located at the University of Pennsylvania’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and the Aga Khan Archives at Harvard University, had long been left in obscurity, and are published in these volumes for the first time. Most of the photographs that had been published earlier in surveys and articles, on the other hand, were either uncredited or attributed to (and in some cases claimed by) other archaeologists and photographers. Ousterhout and Anderson have achieved the remarkable feat of locating and identifying these photographs, and reclaiming them as part of Haynes’ impressive oeuvre. The authors’ insightful accounts on the life and career of Haynes are supplemented by a generous number of illustrations, first-rate photographic reproductions, which add to the charm of these well-designed and handsomely produced volumes. A distinctive aspect of the two books is the care afforded to the writing of captions that serve the illustrations. On first sight one realizes that the lengthy captions are to be read carefully rather than glanced at. They contain detailed explicative accounts, and at times even critical arguments related to the specifics of the photographs, and therefore make a valuable and informative supplement to the main text.

Ousterhout’s John Henry Haynes provides a rich and textured exposition of Haynes’ life-long engagement with archaeology and with what he considered to be its documentary agent, photography. In investigating the photographs Ousterhout makes careful note of sites and buildings that were photographed for the first time, or ones that were damaged or destroyed after they had been recorded by Haynes. These ranged from ancient Assyrian and Hittite finds to Medieval Christian and Seljuk monuments dispersed in an area extending from the northern Aegean into southern Mesopotamia. But beyond a careful examination of individual photographs, the author also engages in a rigorous historical analysis of Haynes’ endeavors, making exhaustive use of archival documentation, such as excavation reports, the personal diaries and letters of Haynes, or the internal correspondences of institutions such as the AIA or University of Pennsylvania’s Babylon Exploration Fund. The archival record enables us to situate Haynes within the dense historical context of late 19th century American academia and trace out his career within the dynamics of frenzied archaeological activity. We not only grasp the dreams, challenges and frustrations of a self-made archaeologist witnessing the formative decades of the discipline. We are also able to explore the motives and perceptions of the American archaeological community as they funded and mobilized Haynes, while eventually disregarding his professional output in accordance with broader institutional goals, class hierarchies, personal ambitions and academic rivalries.

The book’s chapters are arranged in chronological order. The first chapter investigates Haynes’ early life and the beginnings of his involvement in archaeology and photography. Ousterhout underlines William J. Stillman’s formative impact on Haynes when the latter was merely an enthusiast of archaeology. Stillman was the director of a failed archaeological mission to Crete organized by the AIA in 1881. Offered a position in the mission, Haynes sailed to Greece, and while waiting for the permit for the mission (which the Ottoman authorities would never grant) he spent about two months with Stillman in Athens. This was the time when Stillman, the expert photographer, taught Haynes the technical aspects of photography.

The second chapter follows Haynes to Assos, an ancient Greek site in western Anatolia, where he worked as the excavation photographer between 1881 and 1883. The images reveal how Haynes brings out the full drama of the site in his first official mission as photographer. In these early experiments, ancient settings and objects are counterpoised by prominently placed figures representing contemporary life in the excavation; workers, horsemen, exotic villagers, or pensive archaeologists. Instances of what Ousterhout calls “intrusive modernity”, such striking contrasts between the present and the past were trademarks of Haynes’ unique approach to archaeological photography.

The third chapter, “Travels with a Camera,” follows Haynes’ photographic explorations through selected images taken in various excursions to Central Anatolia, Syria and Mesopotamia between 1884 and 1887. In the 1884 Cappadocia excursion alone, Haynes took more than 300 photographs. Ousterhout skillfully braids these captivating images with insights he gathers from Haynes’ personal letters and diary entries. With such densely contextualized reading, one gets an intimate sense of the logistical and emotional challenges of travelling and photographing in the Ottoman countryside at the end of the nineteenth century.

The fourth chapter, “Baghdad and Beyond,” focuses on Haynes’ years of professional maturity. It investigates his most significant output as archaeologist at the Nippur Excavation organized by the Babylon Exploration Fund of the University of Pennsylvania. Haynes had been affiliated with the Nippur project since its launching in 1888. Then, through the 1893–1896 and 1898–1900 seasons, he was appointed the director of year-round excavations, simply because other, more accomplished archaeologists were unwilling to withstand the intolerable conditions of the Nippur site. In 1900 Haynes made a major discovery, unearthing 23,000 cuneiform tablets from the Nippur Temple’s scribal office – at which point, the acknowledged Assyriologist H.V. Hilprecht took over the excavation and took full credit for Haynes’ discoveries. This was the final blow to Haynes’ career. Denigrated, and in failing health and mental condition, he retreated to his home in New England. Tracing out these setbacks and tribulations, and with a close eye on quarrels, tensions and rivalries within the excavation sites, Ousterhout’s book provides a sensitive account of Haynes’ shortcomings, his professional aspirations, and their eventual collapse. Exposing Haynes’ disadvantaged position within the academic community as a less educated and less privileged individual from a modest background, the book skillfully lays bare the reasons for the long-term obscurity of this archaeological pioneer.

The final chapter of Ousterhout’s book foregrounds Haynes as a photographer and investigates his works from an aesthetic viewpoint. The chapter includes a detailed account on the artistic outlook of William Stillman, Haynes’ mentor and main source of inspiration in the photographic trade. With a careful comparison of Haynes’ photographs with those of Stillman, Ousterhout traces back the former’s technique and outlook to its roots in the picturesque aesthetics of the nineteenth century, especially the kind that was promoted by the spiritus rector of Medievalism, John Ruskin. While Haynes regarded photography as mere fact and documentation, Ousterhout observes a unique subjective vision and an aesthetic sensibility that charge his photographs with a distinct energy. Thanks to the formative impact of Stillman, the author argues, Haynes was able to combine the analytical and technical aspects of archaeological photography with the aesthetic sensitivities of the picturesque. This distinctive stance, Ousterhout claims, makes Haynes the “unknown father” of American archaeological photography.

The second book on Haynes, Palmyra 1885, includes eighty-five of about a hundred photographs Haynes took during his five day search trip to the Syrian site. Most photographs are included at the end of the book in the form of a catalogue; they are beautifully reproduced and organized according to the distinct urban and architectural features of the site. In the first two chapters the authors provide biographical information about Haynes, while also focusing on the specifics of the Wolfe Expedition to Mesopotamia, where he served as field manager and photographer. Anderson and Ousterhout situate the expedition within the broader cultural and intellectual context of nineteenth-century American archaeology, drawing attention to the growing interest in Mesopotamia and the rising allure of Biblical archaeology.

The next chapter, entitled “Palmyra and its Desert Queen,” offers a broad and informative account of Palmyra’s past, extending from its earlier history as an Assyrian settlement, to the short-lived but celebrated reign of Queen Zenobia during the Roman times, to its Mediaeval transformation under the Islamic empires. The authors add further topicality to the subject by extending their analysis to the contemporary misfortunes of the site, which was ruthlessly targeted and damaged by ISIS in 2015. The fourth chapter, “The Topography of Palmyra,” brings into close focus the site and its surroundings, expanding upon its geographic setting, its urban form and design attributes. The authors particularly elaborate upon the singularity of the Roman city, abounding in temples and colonnades, and offer an analytical assessment of its layout and architectural details. They are careful to point out the very conditions of the site at the time it was encountered by the Wolfe team in 1885. The Palmyra visit was a short detour in the Mesopotamian expedition, so none of the team members were well prepared to investigate and evaluate the site. Anderson and Ousterhout, therefore, indicate what was visible and meaningful to Haynes, and what remained vague. Through his diary entries, they highlight Haynes’ occasional mistakes and misattributions as he endeavored to piece together elements of the site.

The fifth chapter, “Beasts, Men and Stones,” addresses the collective image of Palmyra in European imagination from the early modern times into the modern age of archaeological frenzy. The authors draw on the rich reservoir of travel narratives, as well as on a variety of visual resources, such as engravings and prints, to provide a textured account of the Euro-American perceptions of Palmyra. The layered image of the site was remoulded in the nineteenth century with the introduction of photography as a superior documentary instrument. The authors include images of Palmyra by the early photographers of the Middle East such as Louis Vignes or Félix Bonfils, juxtaposing them with Haynes’ later renditions of the setting. While Palmyra was already a well-documented site at the time of Haynes’ visit, the American photographer’s output is still significant in terms of its extensive coverage of the site. Furthermore, for the first tine, we see the site imbued with life in Haynes’ photographs. On account his idiosyncratic photographic stance, particularly his interest in involving elements of contemporary life in his compositions, we are able to witness the rhythm of real life in the ruins as they were animated by local dwellers in 1885. Through what the authors call Haynes’ “unobtrusive” engagement with the site, his images “provide our best view of the ecology of the place, a balance between animals, people and things now fully irrecoverable.” (p. 54)

Foraying into uncharted territory within the history of archaeology, the two books offer a fresh and critical perspective on an unacknowledged pioneer of the field. This makes them appealing and thought-provoking for diverse audiences. Both volumes are extremely informative and, at the same time, revealing and enthralling in terms of their visual content. While generously served with photographic illustrations, the books would have benefited greatly from the addition of maps, which would have helped the readers follow the peripatetic archaeologist in his journeys across a wide and complex geography. That said, there is no question that these well-written and well-illustrated volumes make an original and noteworthy contribution to multiple scholarly fields, as they reinsert John Henry Haynes in the map of photographic and archaeological history.

Ahmet Ersoy is a historian teaching at Boğazici University, ersoya@boun.edu.tr

1. STANDARD

Standard, untracked shipping is available worldwide. However, for high-value or heavy shipments outside the UK and Turkey, we strongly recommend option 2 or 3.

2. TRACKED SHIPPING

You can choose this option when ordering online.

3. EXPRESS SHIPPING

Contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net for a quote.

You can also order directly through subscriptions@cornucopia.net if you are worried about shipping times. We can issue a secure online invoice payable by debit or credit card for your order.

JOHN HENRY HAYNES SPECIAL OFFER

Two magnificently illustrated books from Cornucopia on the photography of John Henry Haynes, unsung hero of American archaeology.

Palmyra 1885: The Wolfe Expedition and the Photographs of John Henry Haynes

John Henry Haynes: A Photographer and Archaeologist in the Ottoman Empire 1881–1900 (2nd edition)

RRP: £42.90

Buy both for just £32

25% subscriber discount

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now