On 26 April I ventured across the Bosphorus to attend a concert by the İstanbul State Symphony Orchestra at the Caddebostan Cultural Centre. It was with some trepidation that I took the Metrobus over the First Bosphorus Bridge to its terminus at Söğütlüçeşme, in the hinterland behind Kadıköy: the sight of the skyscrapers in Ataşehir with their deformed shapes and inhumanly rigid design always fills me with a profound sense of horror. William Blake’s Tyger had nothing on Ataşehir when it comes to ‘fearful symmetry’.

As someone who lived in Pendik in the 1970s, I remember what the Asian side of İstanbul was like in those halcyon days when, on train journeys to and from Haydarpaşa Station, one could still see a large number of wooden villas set in their own gardens, with few buildings exceeding five storeys in height. The spanking new megaresidences now extending their domain further and further along the coast send a chill up my spine. What used to be the peaceful outlying suburbs of Maltepe and Küçükyalı (this latter a place that boasted, during the violent prelude to the military coup of 1980, that it never saw a single politically motivated murder) are now part of the undifferentiated urban sprawl that stretches from Kadıköy to Kaynarca, just beyond Pendik. The whole of this littoral has been transformed into a pitiless concrete jungle in which no self-respecting tiger would think for a moment of burning bright.

But I must beware of allowing spleen to dominate the humours in the body politic. As a carminative antidote I will record my gratitude for the exemplary behaviour of the people who guided me on my way to the concert. Having miscalculated the time it would take for the Metrobus to reach its destination, I was late, and would have been even later had it not been for a helpful minibus driver and his lady passenger who told me at what point along the coast road I needed to get off. I then made my way in haste along a leafy avenue lined with 18-storey tower blocks, dodging past status-symbol pedigree doggies and their well-heeled owners as I did so. The Caddebostan Cultural Centre resembles a shopping mall in appearance, so at first I discounted the possibility that it might house anything more cultural than a selection of emporia selling telephone tat. However, pointed in the right direction by a kind gentleman outside a barber’s shop, I arrived about five minutes into the first movement of Christos Papageorgiou’s Violin Concerto.

My first impression of the Caddebostan Cultural Centre’s concert hall was that the stage was small in relation to the seating area. As for the acoustics – well, let us say that my answer to the question “Were they any good?” would be in the negative. I was gratified to see a large number of the seats occupied, however: the locals seem to like their culture, and to have some respect for it. One might wish they did not applaud every single movement of every work, but one cannot have everything. The staff were friendly and helpful, and allowed me and several others to make our way into the hall, despite the fact that the performance was in progress – though I did hear a member of the audience who had arrived in good time exclaim “Allah, Allah!” at our irruption into the auditorium.

The soloist for the concerto was Mr Olgu Kızılay, who is currently a member of the Tekfen Philharmonic Orchestra and at one time played second violin in the late, much-lamented Borusan Quartet. He was trained at the Dokuz Eylül University State Conservatory in İzmir under Prof Hazar Alapınar, and subsequently received instruction from Prof Joshua Epstein at the Conservatoire de Strasbourg. This was followed by service with a number of orchestras in France and Turkey, so he is by no means lacking in experience. I do not know the provenance of the instrument he plays, but it certainly sounds good. As an aside, he recently told me that the bow he uses was once owned by Fritz Kreisler.

The conductor, Mr Nikos Haliassas (from Athens), immediately grabbed my attention. For one thing, his hand movements were even more expressive than those of the Tekfen Orchestra’s Aziz Shokhakimov, and for another, he never missed a trick: even the most insignificant entry by the cellos or the clarinets was anticipated and duly signalled. According to the programme notes, after graduating from the Athens Conservatoire as a violinist, Mr Haliassas received training in both violin-playing and conducting at the Royal Academy and the Royal School in London. He then did a postgraduate course in conducting at Trinity College. It certainly shows – it is always a pleasure to watch a conductor of such sensitivity and professional excellence in action.

As for the concerto itself, I cannot say that the first and last movements exhibited much originality, being examples of the modern trend towards less-than-meaningful chords and fuzziness in the sense-of-direction area. I could not identify much in the way of themes, either, and the complexity of the orchestration was not always justified by the material. Nonetheless, there were pleasing moments in the second movement, a lullaby, and after my rushed journey I was more than ready for some relaxing adagio treatment. It was in this movement, too, that Olgu Kızılay got into his stride, producing a most pleasing tone topped with lashings of voluptuous vibrato. The finale made a nod or two towards folk music; there were quite a few open fourths, but not nearly as many as would have been required to provoke gasps of recognition in a Turkish audience. Still, the orchestra responded well to the conductor’s careful guidance, and for the most part coordinated well with the soloist. As an encore Mr Kızılay gave us a sentimental piece of his own composition from his recent album, which I believe was recorded in Istanbul under the baton of none other than Mr Haliassas. It was well received by the audience. (The orchestration, by the way, was by İlyas Mirzayev, of whom more anon.)

I cannot find a recording of the violin concerto on YouTube, but performances of other works by Christos Papageorgiou are available. Here is Pyrrichios (part of a longer work entitled Choros) that exhibits those open fourths I spoke of earlier. The parallels (no pun intended) with Turkish folk music are very much in evidence:

Now, here is Olgu Kızılay in a performance of İlyas Mirzayev’s Adagio for Violin and Orchestra, conducted by Nikos Haliassas in the Ahmed Adnan Saygun Cultural Centre in İzmir, a venue celebrated among Turkey’s musicians for the excellence of its acoustics:

At this point, I cannot resist a trip down memory lane to honour the Borusan Quartet, seen here in a performance of the third movement of İlyas Mirzayev’s String Quartet No 3 – a piece that here does duty as an elegy for an excellent ensemble. It is in fact based on a Turkish song by the name of Sarıkamış Türküsü. The song commemorates a battle in December 1914 and January 1915 in which around 60,000 Ottoman soldiers died – many from exposure – in an abortive attempt to take on the invading Russian army in the rear at Sarıkamış, between Erzurum and Kars. Enver Pasha had insisted that they march over the Allahüekber Mountains in the dead of winter. Many of the troops were already dying of typhus, cholera, dysentery and other diseases and, moreover, were inadequately clothed for the freezing weather. (Ottoman soldiers on the eastern front in the First World War sometimes had nothing but makeshift wooden sandals, or even rags, on their feet, and looked with envy and astonishment at the boots worn by captured Russians.) The small number who survived the madcap march were unsuccessful in dislodging the Russians, and Enver Pasha subsequently gagged the press in Istanbul to make sure no one heard of the disaster.

So here is the recording of the Sarıkamış Türküsü movement. Olgu Kızılay is second from the left (his hair was longer then), but keep your eye on the cellist: the col legno strikings with the bow that begin at 02:57 are not the only trick he gets up to – you need to watch to the end:

During the interval I searched in vain for somewhere selling Turkish coffee. Instead, I found solace in the artwork on display in the foyer, where someone had lovingly reproduced posters for Turkish films of yesteryear starring the likes of Türkân Şoray and Kadir İnanır. I was taken momentarily back to the 1970s with their crackly films and tinny soundtracks – those long-lost days when the pop music they played in dolmuşes and minibuses was actually worth listening to. But I must lay down my recidivist spear and return to the concert.

The second half consisted of Debussy’s Danse Sacré et Danse Profane for harp and orchestra, and Bizet’s Carmen Suites 1 and 2. The first of these two works was written in 1904 at the request of the Pleyel firm in Paris, the intention being to showcase their newly-invented model of harp – which instead of the usual pedals (allowing the harpist to move the pitch of the single set of strings up and down to varying degrees) had multiple strings, one for each chromatic note. This, however, made the new-fangled instrument prohibitively heavy, so Debussy very sensibly wrote his piece in such a way as to make it playable on the more conventional type of harp (in any case, Pleyel’s invention did not catch on). It remains one of the kingpins of the repertoire.

Merve Kocabeyler, the soloist for the Debussy, began her training (at the age of 11) at the İstanbul University State Conservatory as a pupil of Yonca Bilenoğlu. Then, having won a scholarship to the Salzburg Mozarteum University, she studied with Prof Helga Storck and Prof Stephen Fitzpatrick. Following this, she received lessons from Prof Erika Waardenburg at the Conservatorium van Amsterdam, and completed her training with a further session at the Mozarteum. Although not yet 30, she has already won awards in several international competitions, and in 2012 was named ‘Young Musician of the Year’ by the Donizetti Classical Music Awards. The harp she performs on is apparently the gift of the Aydın Doğan Foundation and Fazıl Say.

My apologies to Ms Kocabeyler for presenting a video of Debussy’s Danse Sacré et Danse Profane played by another harpist (one Sasha Boldachev), but I had no choice: there does not seem to be a video of her playing it on YouTube. Debussy’s harmonies – especially the augmented intervals and whole-tone scales – work extremely well on this instrument:

Fortunately, videos do exist of Merve performing other works. First, here she is in Bach’s Sarabande from the Lute Suite (BWV 996). The black-and-white treatment makes this piece, with its gorgeously resonating bass notes, really atmospheric:

Now for something more in the virtuoso line: the Introduction and Variations on Airs from Bellini’s ‘Norma’ by a certain Eli Parish. Warning: although there are no visuals for this video, the volume is loud, so turn the sound down in good time:

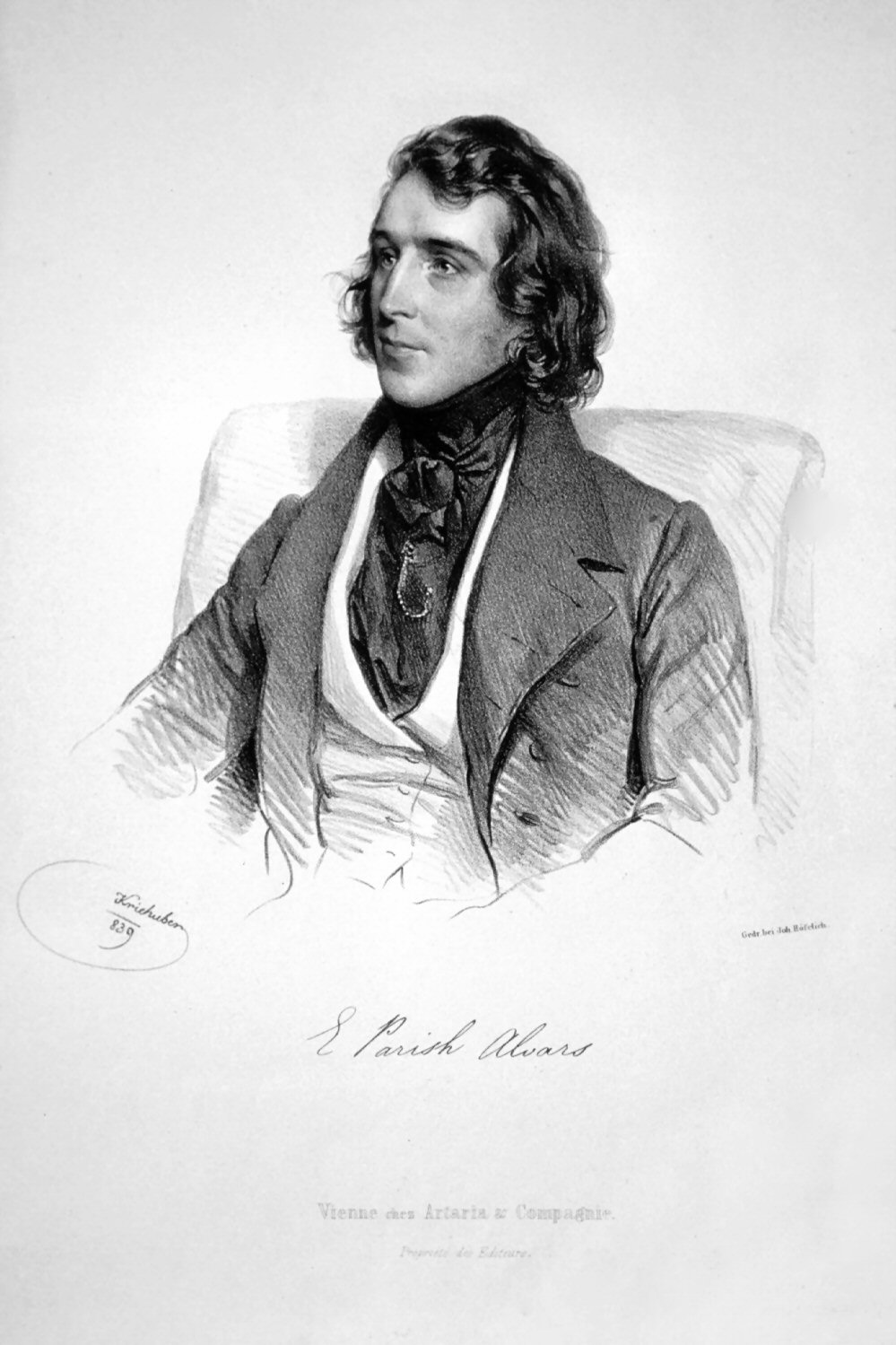

Eli Parish, born in Teignmouth, Devonshire in 1808, turns out to be a really interesting cat. The son of an organist and singing teacher, he went to London to study the harp at the age of 12 but was subsequently unable to attend the Royal College as he was unable to pay the fees. In 1828 he left for Florence, whither he had been invited by Lord Burghersh, the British Ambassador in that city. (Burghersh, a composer, was in fact the founder of the Royal Academy of Music.) Parish now began to study composition, and at the same time started using the pseudonym ‘Albert Alvars’. Two years later, the young harpist embarked on a series of concert tours that took him to Germany, Denmark, Sweden and Russia, and in the spring of 1832 he set off for – wait for it – Constantinople, where he remained for about three months. During that time he gave a number of concerts for Sultan Mahmud II. Later in that year, ‘Albert Alvars’ moved to Vienna, where he settled.

His career now took off in a big way, and he travelled all over Europe giving recitals that included his own compositions and arrangements (of which there were a prodigious number). In 1842, after a concert in Germany, Franz Liszt wrote the following description of him:

Our bard has a somewhat rugged appearance: his gigantic figure, with his square shoulders, recalls the mountain peasant. His face is comparatively mature for his years, and from underneath his prominent forehead speak his dreamy eyes, expressive of the glowing imagination which lives in his compositions.

The following year, Eli made quite an impression on Hector Berlioz, as we see from this latter’s memoirs:

In Dresden, I met the prodigious English harpist Elias Parish Alvars, a name not yet as renowned as it ought to be. He had just come from Vienna. This man is the Liszt of the harp. You cannot conceive all the delicate and powerful effects, the novel touches and unprecedented sonorities, that he manages to produce from an instrument in many respects so limited.

Vienna, however, turned out to be an unfortunate choice as Eli Parish’s place of residence. Having witnessed the revolution of 1848, he died there in poverty in January 1849. Our hero may indeed have been awarded the title of ‘Imperial Virtuoso’, but the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde had stopped paying his salary, and all his aristocratic pupils had fled the city owing to the riots that had broken out in protest at Metternich’s repressive régime.

If you wish to learn more about this Devonshire man turned internationally famous harpist, there is an excellent website about him: parishalvars.com/

And so, digressions and excursions over, we return to the subject of the concert on April 26. Merve Kocabeyler’s performance in the Debussy was excellent, and the lengthy applause she received well deserved. She followed it up with an encore – a piece entitled Rainbow, specially written for this concert by the Azeri composer İlyas Mirzayev, who received his initial training at the Conservatoire in Baku and then went on to take a second degree in composition at the Moscow Conservatoire. Orchestration is his speciality, and at one stage he worked with the Berliner Philharmoniker. Many of his past works were commissioned by the Tekfen Philharmonic. These include his second symphony, the Symphony of Three Seas, and his Black Sea Rhapsody. As one would expect from a composer who knows his instruments inside out, Rainbow was eminently suitable for the harp, and Merve Kocabeyler’s rendition of the glissandi – especially the pianissimo ones – was a real treat.

The proceedings concluded with a performance of Bizet’s Carmen (Suites 1 and 2). This is a well-known work with lots of rousing stuff in the minor key. Spain, the location in which the eponymous opera was set, is of course similar to Turkey in its preference for the minor over the major, and it is hardly surprising that these suites (adapted from the opera by Bizet’s friend Ernest Guiraud after the composer’s death in 1875 at the age of 37) goes down well in Turkey’s concert halls. The following performance by the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra is particularly well recorded:

I must say that things continue to look up for the İstanbul State Symphony Orchestra. They performed at least adequately when accompanying the violinist, competently when accompanying the harpist, and in Carmen they really shone. This may have been due partly to the outstanding abilities of the conductor, and partly to the fact that they resonated well with what they were playing, but all the same…

Opposite the concert hall I found somewhere where I could have a Turkish coffee and a squishy cake, and thus fortified I clasped not the deadly terrors of the Tyger’s brain in Blake’s poem, but the overhead rail in the Metrobus back over the Bosphorus Bridge – not feeling at all like watering heaven with my tears, but satisfied, and indeed pleasantly surprised, after a concert that I thought was a most impressive showing by some of Turkey’s young musicians. And it was too dark to see Ataşehir.

_The_Golden_Horn_at_Dusk_c._1900_140_92_80.jpg)