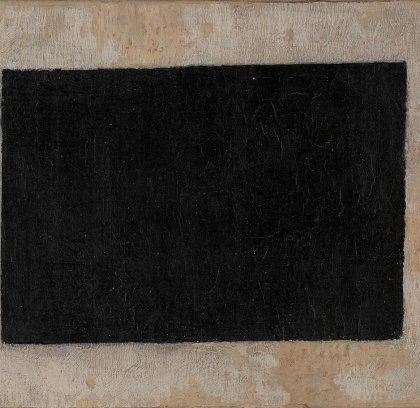

It’s been 73 years since George Costakis saw Olga Rozanova’s Green Stripe in a Moscow studio and started the collection that, to paraphrase the art historian Margit Rowell, required the history of 20th-century art to be rewritten. Rewritten not just because of the sheer volume and quality of works by a single generation of radically experimental and gifted Russian artists, but also because of works like Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square, which presented evidence that this generation had in ways been far ahead of Western European modernism’s developmental curve, burning through the potentialities of art at an unprecedented pace until history, death and Stalin intervened.

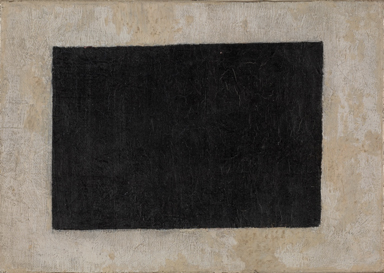

Kazimir Malevich, Black Quadrilateral (1915)

Malevich’s Black Square is not presented as part of The Russian Avant-Garde: Dreaming the Future through Art and Design, currently running at Istanbul’s Sakıp Sabancı Museum (until April 7, 2019), but his Black Quadrilateral is. The Costakis Collection, divided evenly between the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and the State Museum of Contemporary Art in Thessaloniki, Greece, is so large (estimated at over 2500 works) that despite dozens of exhibitions since its first debut outside Russia, in Düsseldorf in 1977, it continues to present fresh incarnations to new audiences. Aside from being the first major presentation of the Russian avant-garde in Turkey, this exhibition adds something new to the movement’s international lineage by combining pieces from the Costakis collection with a rich selection of post-revolutionary painted porcelain and costumes from Moscow’s All-Russian Decorative Art Museum.

If there is a criticism to be made of the curation, it is not in the artworks, but in the accompanying text. The exhibition begins with a corridor of it, covering the key political and cultural events in Russia from the end of the 19th century to the mid-1930s. Comprised of several thousand words of chronological fact, I personally left this corridor more dispirited than enlightened. The lengthy panels in each room, which summarise a series of periods, movements and schools – ‘pre-avant-garde’, ‘cubo-futurism’, ‘suprematism and non-objective art’, ‘The School of Organic Culture’, ‘analytic art’, ‘constructivism’, etc – are somewhat better, but feel similarly burdened by the need to be comprehensive. The admittedly huge task of contextualising 513 works as diverse as this might have been better served by a few forays into human detail, narrative or subjective opinion.

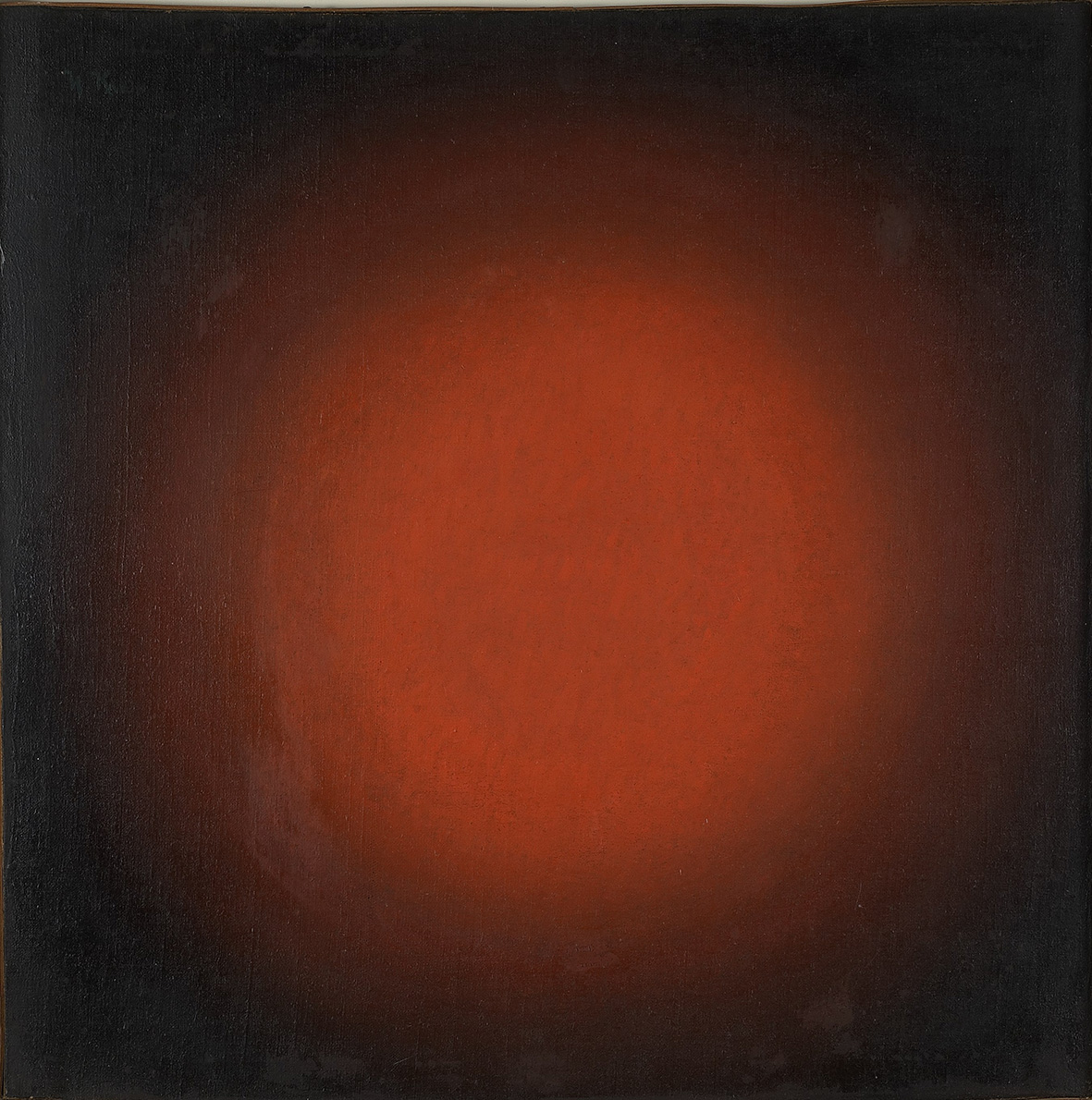

Lyubov Popova, Spatial Force Construction (1921)

,_Lyubov_Popova_large.jpeg)