Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital Edition

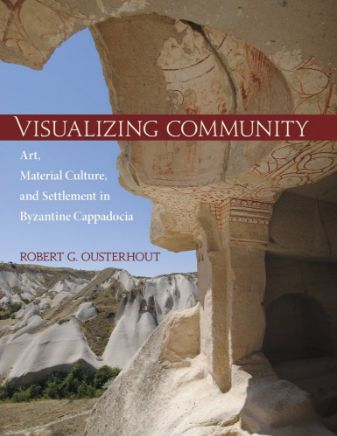

Art, Material Culture, and Settlement in Byzantine Cappadocia

Cappadocia, a picturesque volcanic region of central Anatolia, preserves the best evidence of daily life in the Byzantine Empire and yet remains remarkably understudied, better known to tourists than to scholars. The area preserves an abundance of physical remains: at least a thousand rock-cut churches or chapels, of which more than one-third retain significant elements of their painted decoration, as well as monasteries, houses, entire towns and villages, underground refuges, agricultural installations, storage facilities, hydrological interventions, and countless other examples of non-ecclesiastical architecture. In dramatic contrast to its dearth of textual evidence, Cappadocia is unrivaled in the Byzantine world for its material culture.

Based upon the close analysis of material and visual residues, Visualizing Community offers a critical reassessment of the story and historiography of Byzantine Cappadocia, with chapters devoted to its architecture and painting, as well as to its secular and spiritual landscapes. In the absence of a written record, it may never be possible to write a traditional history of the region, but, as Robert Ousterhout shows, it is possible to visualize the kinds of communities that once formed the living landscape of Cappadocia.

The region of Cappadocia in central Anatolia is famous for its landscape: layers of ash and lava, eroded by wind and water, have been shaped over time into a succession of valleys and outcrops, the latter often curiously shaped as cones, domes, and occasionally gigantic mushrooms. Within this phantasmagorical setting its medieval Byzantine inhabitants excavated at least one thousand rock-cut churches and chapels, of which over a third preserve some of their painted decoration. In addition, the region contains more than 40 multi-storey underground complexes, with rooms and corridors defended by rolling stone doors, as well as rockcarved monasteries, houses, and villages with their agricultural installations, including winepresses, mills, apiaries, dovecotes and stables.

Visualizing Community, written by Prof. Robert Ousterhout of the University of Pennsylvania and beautifully produced by Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, DC, provides for the first time a systematic account of this wealth of habitation. The book has important new ideas to offer, while it draws together and interprets the abundant but widely scattered scholarship from the past. Previous writers had tended to prioritise the study of then paintings in the churches; this book, however, takes a fresh perspective that integrates the rock-cut architecture both with its internal decoration and with its external setting in the inhabited landscape.

As the author notes, there are very few written sources, particularly from the medieval period, that throw light on the history of Cappadocia. The region is rich in its material remains, but poor in its textual record, apart from the inscriptions on the monuments themselves. Thus the evidence has to come from the landscape and the remains of its settlement. This is the material that furnishes the author with his “text”, and he reads it with extraordinary care.

Many earlier writers on Cappadocia had believed the rock-cut complexes to be monasteries, on the supposition that they had been excavated by Christian monks fleeing persecution. The author, on the other hand, argues that a number of the complexes were large houses, with halls and kitchens excavated behind impressive rock-cut façades. For example, at Soğanlı a substantial rock-cut residence and a monastery faced each other on opposite sides of a valley. The author proposes that John Skepides, who is recorded together with his court titles in a long inscription in the monastic church, may have been both the donor of the monastery and the owner of the nearby mansion.

The book itself comprises four chapters, the first of which focuses on the interaction between rock-cut and masonry architecture, comparing the cave churches with the relatively few freestanding Byzantine churches in Cappadocia as well as examples outside the region. The second chapter is devoted to the decoration of the churches, including the working practices of the painters, the relationship of the paintings to their architectural settings, and the role of inscriptions within the churches. The third chapter uses the evidence of surviving settlements to reconstruct aspects of daily life in medieval Byzantium, including agriculture, security and domestic arrangements at different social levels. The last chapter discusses death in medieval Cappadocia, considering cemeteries and commemorative spaces. It focuses particularly on the problems of interpretation posed by the caves in the much-visited Göreme area, with its apparent overabundance of churches, chapels and refectories.

Some of the most interesting and important observations in the book concern the relationship of rock-cut to built architecture. The excavated churches are often small, or, as the author puts it, “miniaturized”. They are also notable for reproducing elements of built architecture, such as columns, capitals, pilasters, ribbed groin vaults, banded barrel vaults, domes with pendentives and, occasionally, squinches, together with liturgical furnishings including altars, pulpits and sanctuary screens (above and top). Since the rock-cut churches did not have to obey structural laws, they could evoke masonry architecture by replicating its forms, but they did not have to assemble the elements in a way that complied with the structural logic of freestanding buildings. Often the architectural detailing was exaggerated, as if to declare loudly: “This is architecture” – a phenomenon that the author calls calls “architectonicity”.

The liturgical furnishings present a conundrum typical of Cappadocia. While they are relatively well preserved in the rock-cut churches, in contrast to masonry churches elsewhere in Byzantium, we have no textual information on the liturgies performed in those spaces. In Constantinople, on the other hand, we have liturgies preserved in texts, but a near-total lack of liturgical furnishings in the surviving monuments. But just as the churches in Cappadocia often were miniaturised, so too was their furniture. The author sites a pulpit at Durmuş Kadır Kilisesi and Avcılar, for example, that would have challenged anyone to remain upright while reading from it (below left). He suggests that in such cases the carving of liturgical spaces represented “liturgicality”, in that these fittings may have been more for show than for the actual performance of services. He concludes that many of the caves should be considered more as commemorative chapels than as functioning churches.

The miniaturised spaces were essentially symbolic, carved and decorated to serve the dead rather than the living. Holy bishops painted on the walls of their sanctuaries eternally conducted services to benefit the souls of the deceased; orderly ranks of painted soldier-saints guarded the buries; images of the Virgin and of John the Baptist standing before the throne of Christ in the apses ceaselessly conveyed the petitions of the dead. The author goes so far as to draw a comparison between the cave chapels of Cappadocia and the tombs of the ancient Egyptians, as both were fitted out to provide the deceased with what they would need in the afterlife, albeit in very different ways.

The book concludes by arguing that Cappadocia should not be seen as a sacred landscape similar to Mount Athos, solely inhabited by monks. Rather, it was an area given over to both secular and religious pursuits, which demanded houses and agricultural complexes as much as monasteries and commemorative chapels for the dead.

Finally, credit should be given to the lavish illustration of this book, which includes a wealth of plans and elevations, many newly produced by the author, as well as numerous colour photographs, most of them also taken by him. The photographs reveal the author as an archaeologist with a sense of poetry, for several of them are evocative, and at times even dramatic. These qualities are conveyed in the image on the book’s jacket, a striking record of the half-destroyed apse of Church One at Balkan Deresi, which gapes ominously above a prospect of the valley far below. In another carefully composed shot (left), a ruined arch belonging to Church Two of Kemerli Kilise at Vıranşehir frames a scene of a mountain rising partly sunlit in the distance. A view of the ruined skeleton of Kızıl Kilise at Sivrihisar shows four isolated arches at the centre of the building raising aloft a dome still miraculously intact against a blue sky, in spite of the depredations of time. Another photograph (below) suggests the spiritual ascent of a Byzantine ascetic through the image of a wooden ladder, which leads us up step by step to the Hermitage of Symeon at Paşabağı. The book closes with a splendid view of Cappadocia looking eastwards from Uçhisar, inviting us to read its multicoloured strata of landscape layer by layer, and thus to uncover the complexities of its past. To those complexities we could have no better guide than the author.

Henry Maguire is a former Director of Byzantine Studies at Dumbarton Oaks and Professor of Art History at John Hopkins University. ‘Byzantine Magic’, ed. Henry Maguire (Dumbarton Oaks) is available here for £15.95

Out of Stock

Out of Stock

Buy from Amazon

Buy from Amazon

1. STANDARD

Standard, untracked shipping is available worldwide. However, for high-value or heavy shipments outside the UK and Turkey, we strongly recommend option 2 or 3.

2. TRACKED SHIPPING

You can choose this option when ordering online.

3. EXPRESS SHIPPING

Contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net for a quote.

You can also order directly through subscriptions@cornucopia.net if you are worried about shipping times. We can issue a secure online invoice payable by debit or credit card for your order.

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now