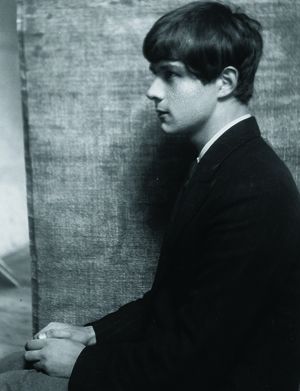

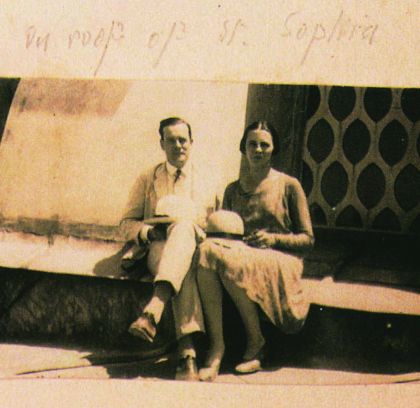

It was with enormous sadness that we learned of the passing of the great Byzantine historian Anthony Bryer. The funeral service was held yesterday at St Peter's Church, Harborne, in Birmingham. Professor Emeritus of Byzantine Studies at the University of Birmingham, or simply Bryer, as he was known to all, he inspired generations of Byzantinists with his unique mixture of erudition, compassion and gentle wit. He will be sorely missed throughout the Byzantine and Ottoman worlds. Our sympathy goes to his wife, Jenny, and to his family and many friends.

Cornucopia owes an enormous debt to Bryer. He generously contributed to the magazine from the very start and indeed was one of its inspirations. Typical of Bryer's eye for detail, his knack of rooting history in the real living world, and his sparkling humour was his article on Aya Sofya in the first issue, published in 1992. In memory of a wise, kind man and a masterful historian, we offer this delightful extract:

THE MIRACLE OF SANTA SOPHIA

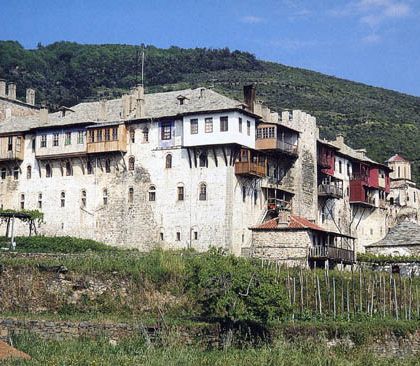

A medieval writer trying to describe an elephant to people who had never seen one began: ‘It has a small tail.’ Anyone who has tried to describe the domed basilica of Santa Sophia in Istanbul will sympathise. But you have to start somewhere. In 1894 WR Lethaby began with the words ‘Sancta Sophia is the most interesting building on the world's surface.’ It is a start.

Cathedrals are dedicated to local patrons but Constantinople – Byzantine Istanbul – was an upstart place in the Roman world. Few have heard of its local martyr, St Mokios: his cistern is now a vegetable garden, impossible to find unless you happen to fall into it.

The city was to come under the patronage of the Mother of God, but the Cathedral, first opened on February 15, 360, could only be called the great Church. By about 430, people also called it the Holy Wisdom of God. Its feast day was Christmas Day when the Holy Wisdom (Haghia or Santa Sophia) became incarnate.

The original Great Church was burned down in a rumpus on June 20, 404. Theodosius replaced it with a massive basilica which was burned down in the Nika riots against Justinian on the night of January 12, 532.

Anyone who knows what a January night can be like in Istanbul may suspect the Hippodrome mob of trying to keep warm. But the reaction of dictators who survive a coup is swift. The site was cleared and Justinian began rebuilding Santa Sophia on February 23, 532. On December 27, 537, he reopened the Great Church which stands today. Such speed is a clue to what makes it the most interesting building on the world’s surface.

In 537, Santa Sophia was probably the largest building on the world’s surface, barring Egyptian pyramids, or the Great Wall of China. It still probably sports the widest unsupported brick dome in the world – about the size of the Albert Hall in London.

How can you describe such scale? One sportsman eyed a pigeon in the dome and remarked ‘Out of shot’, which is a kind of measurement.

It stands on the burnt debris of its predecessors, but also literally on the world’s surface, without foundations, and in an earthquake belt. The first dome was thrown down in an earthquake in 558; Justinian lived long enough to reinaugurate the present higher dome on Christmas Eve 562. Later, segments crashed to the floor in 989 and 1346 (when it was buttressed).

Visitors are happily unaware that they walk under an estimated one thousand tons of unsecured glass. At night, when the crowds have gone, you can hear the mosaic cubes patter down like diant dandruff and sense myriads of hairline cracks in the masonry adjust to the temperature and tiny tremors of the world’s world’s surface as the Great Church settles down to sleep.

But it survives. Most cathedrals take decades to craft: Santa Sophia was built in under six years. Maybe that is the reason.

Justinian’s subjects must have been as awestruck as any citizen of Romania who saw Ceaucescu’s palace go up so fast and grandiosely at their expense. The logistics of numbering marble slabs, ordering capitals, assembling reused columns, meting lead and baking bricks must have been a contractor’s nightmare. Everything was going on at once by the autumn of 535.

But Santa Sophia will long outlive the work of other dictators – barring pyramid-builders. The mortar was not given time to set brittle before it was saddled with quarter and half domes which skewed out of place and are still gently adjusting. The architectonics of Santa Sophia remain mysterious. Such a happy accident cannot be repeated and never was. It was a one-off.

The Miracle of Santa Sophia, by Anthony Bryer, appeard in Cornucopia No 1, 1992

_x_sm__420_408_80_c1.jpg)