In medias res, the curtain rising on the action in full flow, might seem an odd eulogy to recite over the memory of a dear friend, but Robert Chenciner was someone in perpetual motion and even now it is hard to think of him as being still. Think Christopher Lloyd’s ‘Doc’ in Back to the Future or Alice’s White Rabbit; blink and you would miss him dashing in pursuit of a project more exciting or eccentric than the last.

No subject was too broad or too arcane for him not to show an interest, be it the chemistry of natural textile dyes or the monumental dry-stone Ingush towers of the North Caucasus. And no matter how many days, months or years had elapsed since you last saw ‘Chence’, he would grab you by the scruff of your neck and take you with him to his next adventure. It was thanks to Bob I first went to tea (well, instant coffee) inside a New York-license-plated Volkswagen bus parked in Istanbul’s Rumelihisarı to meet the great photographer and textile authority Josephine Powell. Thanks to Bob (maybe ‘thanks’ is not the right word) I responded to a late-night call pleading for help in coping with an unruly house guest, the chief architect of the city of Baku, Azerbaijan, who was hell-bent on going to the Raymond Revue Bar in London’s Soho. And it was on a calmer, sunny afternoon that I went to the open-air book launch in Regent’s Park of Bob’s Tattooed Mountain Women and Spoonboxes of Daghestan – a work narrowly defeated (unjustly, in my opinion) by the far more prosaic The Stray Shopping Carts of Eastern North America for the coveted Bookseller/Diagram prize of oddest book title of 2006.

Bob lost his father when he was only five and moved with his mother to Canada. She died shortly after and he was sponsored by an uncle to return to England to complete his education. He ended up reading mechanical sciences (aka engineering) at Cambridge and I suppose this embedded in him the need to understand how bits came together to make things work. But he was possessed of talents that no formal schooling could impart, particularly a powerful aesthetic imagination. He had an extraordinary eye and other friends describe, if not a photographic memory, an ability to catalogue in his mind, pretty much anything he saw. He did not discover kaitags – the antique silk-embroidered cottons made in the Caucasus, but he spotted them, researched and wrote about them, and saw their value skyrocket in the salesroom. He was a businessman as well as scholar, a collector and a dealer, but underpinning it all was an ability to spot the flower among the thorns.

His interest was not in celebrity or conceptual art, but in the anonymity of craft: the weavers or carpenters who may not have been quite aware just how astonishing their talents were. Unlike many collectors, he had a sense of context and place. In his ‘material cultural memoir’, Dragons, Padlocks and Tamerlane’s Balls, he writes of an obligation to collect the work of the present as well as the past and decided, ‘in the tradition of the English gentleman traveller, I should commission something special – my own dinner service… I drew pistol knives, three-pronged forks and large-bowled Byzantine spoons both with complex Roman mounts about rat-tailed supports.’ The cutlery set of six was a project that took over 25 years and involved co-opting (by my count) eight separate craftsmen, thousands of miles apart, to complete. I never actually saw the famous 1925 two-seat Clyno convertible, which he brought for £30 from a ‘tinker-scrap man’ as a student, but understood it could do 0 to 60 in the decades it took lovingly to repair.

Bob became a Senior Associate Member at St Antony’s College Oxford and was similarly honoured as member of the Russian Academy of Sciences at the Daghestan Scientific Centre in 1990. He could identify the design on a Caucasian Lesghi carpet at a thousand paces. He was brimming with knowledge and insight. Yet there was something mischievous about his approach which frightened more traditional academics. No better example of this was the Observer front-page furore he caused at the Oxford Food Symposium when he declared the Bayeux Tapestry to be a forgery, or at least a much-oversewn piece of cloth. He reasoned it would have been unlikely for Norman knights to be depicted celebrating victory over the Saxons by grilling skewers of meat over charcoal braziers. There were no kebab takeaways in the Hastings of 1066 and it wasn’t until the Ottomans visited Versailles in the mid-18th century that Turkish food came to France. The museum director at Bayeux demanded a retraction.

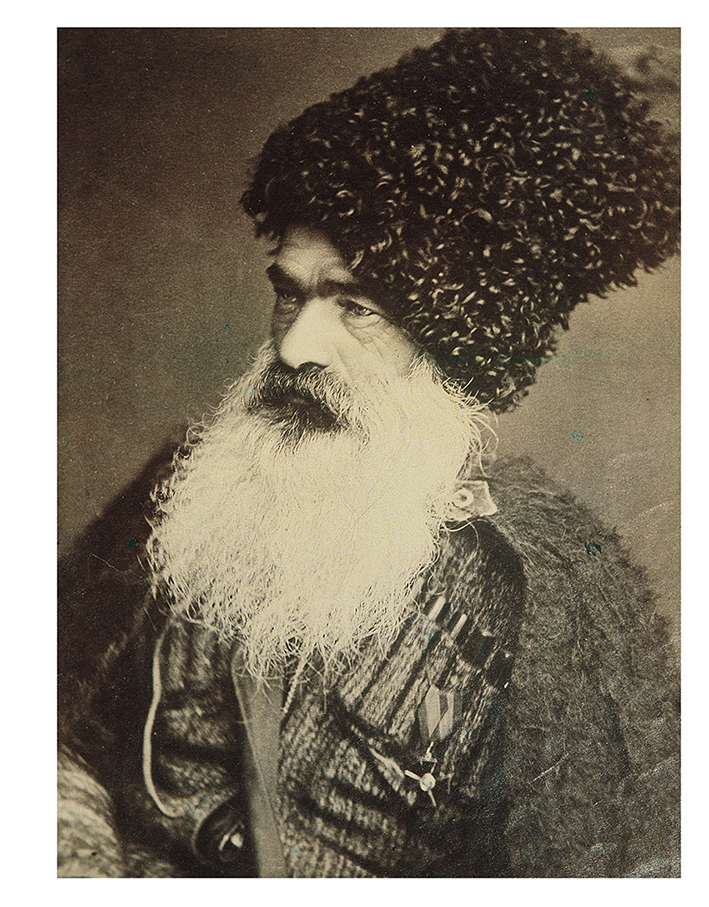

Kabardin elder (Russian Museum of Ethnography, St Petersburg) This aszheghafe (or wearer of the goatskin) is dressed in a hairy, round-shouldered felt bourka – in Chechnya and Daghestan bourkas have square shoulders and longer hairs. His tall papakha hat is of karakul lamb's fleece with a chamois-leather top. The medal on his banderole is Russian (Robert Chenciner, 'The Peoples that Time Forgot', Cornucopia 28)

Chence’s love for the Caucasus is reflected in the cover story he did for Cornucopia (issue 28), a review of the extraordinary photos of the region collected by the Russian Ethnographic Museum in St Petersburg either side of the First World War. His Daghestan: Tradition & Survival (1997) was the product of his frequent visits there, and in 2007 the Sakıp Sabancı Museum displayed to spectacular effect his collection of kaitag embroideries to coincide with that year’s International Conference on Oriental Carpets (ICOC) in Istanbul.

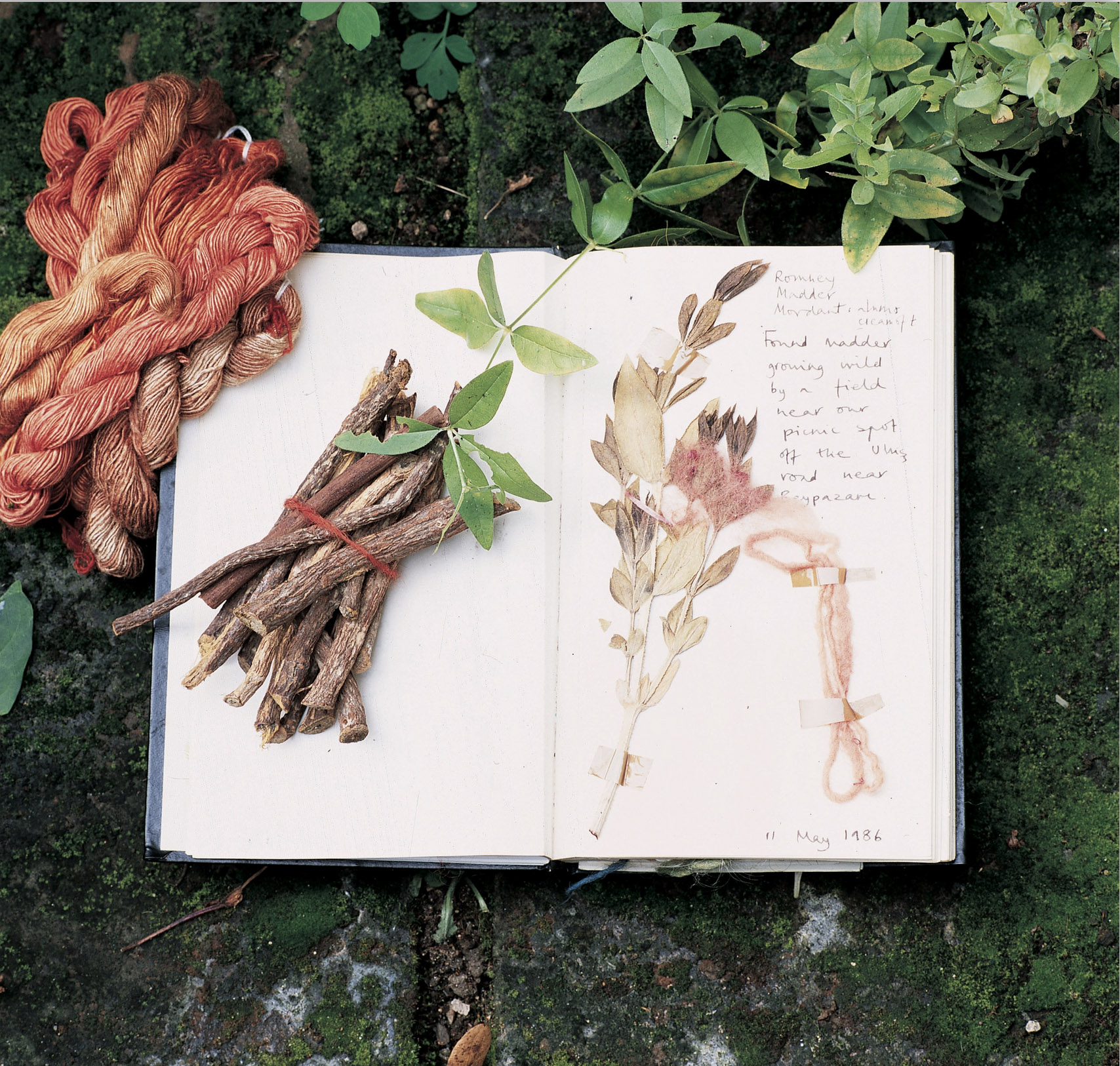

Issue 24 of Cornucopia also contains a review by Barnaby Rogerson of Bob’s Madder Red: A History of Luxury and Trade, along with a playful interview that captures that relentless desire to know everything that could be known about how to dye textiles the colour red. The article is beautiful to look at (the photo essay by Simon Upton is styled by the late World of Interiors founder Min Hogg) but also touching for the page-and-a-half bleed depicting a thread of dyed wool pasted next to a clump of madder root in the daybook of Bob’s wife, Marian. ‘Found madder growing wild by a field near our picnic spot off the Uluş road near Beypazarı’ is the entry. Deprived of family at a young age, Bob’s fondest achievement was to create a family of his own. To Marian and daughters Louisa and Isabel go condolences from all of us who were touched by his life.

Robert Chenciner, b. London 1945 (or 46), d. London 2021.

_The_Golden_Horn_at_Dusk_c._1900_140_92_80.jpg)