Image © Kayhan Kaygusuz, courtesy of IKSV

Climate change makes the sea level rise. Blustering politicians armed with nuclear weapons pursue reckless policies, and the doomsday clock ticks closer to midnight. Earthquakes threaten the city on the Bosphorus, where the memory of 1999 lingers long, though maybe not long enough. Migrants flee war and flood countries that want to shut their borders and avert their eyes. Our social media accounts sell our data. The government watches us, always. As the world inches closer and closer to apocalypse, we’re left to grapple: how can we live in this age?

Throughout the 4th Istanbul Design Biennial, artists and designers delve into the dread that permeates our modern lives. The official theme is ‘A School of Schools,’ an ‘educational web of design strategies’ positing that ‘new ideas can happen anywhere’. But it seems to me that the true throughline for many of the projects on display is the design of global dread.

We are not trying to become super humans; we are trying to survive. We are trying to learn from a past that threatens to capsise our present.

The School of Earthquake Diplomacy, photo by Kayhan Kaygusuz

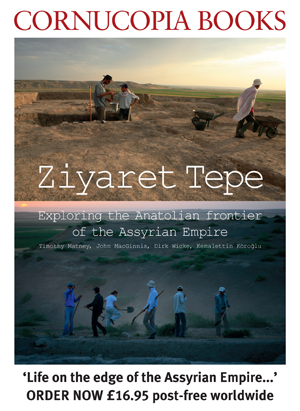

In Istanbul the biggest threat to us is the ground beneath our feet. Navine G Khan-Dossos’s project, The School of Earthquake Diplomacy, at ARTER’s ‘Earth School’, takes an optimistic look at the twin 1999 earthquakes that struck Turkey and Greece, and at the way each country offered reciprocal support – healing old diplomatic wounds in the process. Working with researchers at MEF University and Boğaziçi University, Khan-Dossos posits a plan for floating emergency housing in the Golden Horn, a safe harbour when the tectonic plates shift. And yet the true dread of ‘the big one’ infuses the colourful graphics and shiny diagrams that make up the project.

Cihad Caner’s project at the ‘Earth School’ looks to the past as well, focusing on the water crisis that struck Syria between 2006 and 2010 and how it precluded the wave of migration into Europe. The flow of one crisis into another – and the attempt to gain wisdom about designing our future based on our failures in the past – echoes throughout the Biennial.

Image © Kayhan Kaygusuz, courtesy of IKSV

Staying Alive, by the design duo SulSolSal, faces the inevitable apocalypse head-on with a cheeky exploration of ‘doomsday preppers’, drawn from their design research. Presented as a contemporary cabinet of curiosities, the collection is marked by pocket chainsaws (‘Ideal for hunters, campers, hikers, survivalists’), individual packets of ‘emergency drinking water’, a detailed doomsday clock (we are currently at two minutes to midnight, that is, nuclear annihilation), and other pieces of the strange industry that has grown around the end of times. People are preparing for disaster, but what is the disaster?

Ebru Kurbak, Irene Posch, The Embroidered Computer, photo by Kayhan Kaygus

At the ‘Currents School’ in the Yapı Kredi Culture Centre, the mechanics of networks and connection explore the absurd, the subversive, and, inevitably, the heartbreaking. An ornate computer made entirely out of embroidery uses traditionally ‘feminine skills’ to produce a complex electronic object, asking the question: what skills do you need to build a computer? This project, Stitching Worlds by Ebru Kurbak, reminded me of the Antikythera Mechanism, the multi-geared computer dating to roughly 100 BC, recovered from a shipwreck in 1902 and currently residing in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. In the heave of fallen empires, the technology behind the Antikythera Mechanism was lost to Europe for hundreds of years. Will we lose our technology to global cataclysm? In those curlicues of gold embroidery, I sensed that inherent dread.

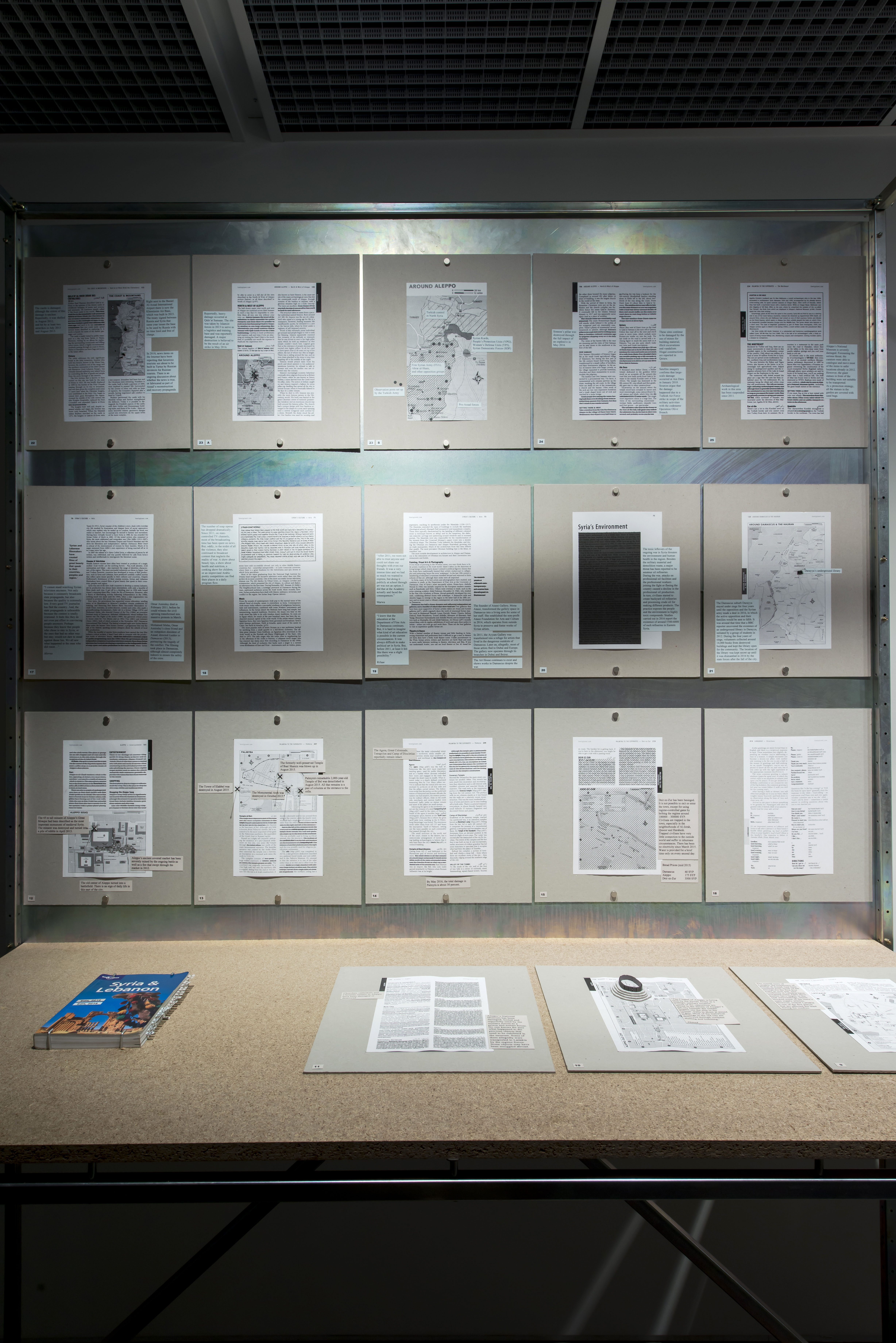

Ebru Kurbak, Lonely Planet, exhibition view at the Istanbul Design Biennial. Photo: Kayhan Kaygusuz

The collective Åbäke tack absurd, looking at information flows through the cartoonish fugu fish which, we are informed, ‘can kill 22, 23 [adults]... and double the amount of children’ if improperly consumed. The danger lurking under the surface of movement becomes more explicit in another project by Ebru Kurbak, where a simple blue book becomes the emotional gut-punch of the biennial. The Syrian Lonely Planet, lit by a solitary light, is presented in a twice-edited version, with strikethroughs and addendums reflecting the state of the country in 2016 and 2018. With descriptions of Syrian hospitality and spectacular archaeological sites overlaid with updates on terror groups, refugees, destruction and death, we are left to contemplate how the past has flowed into this dread present.

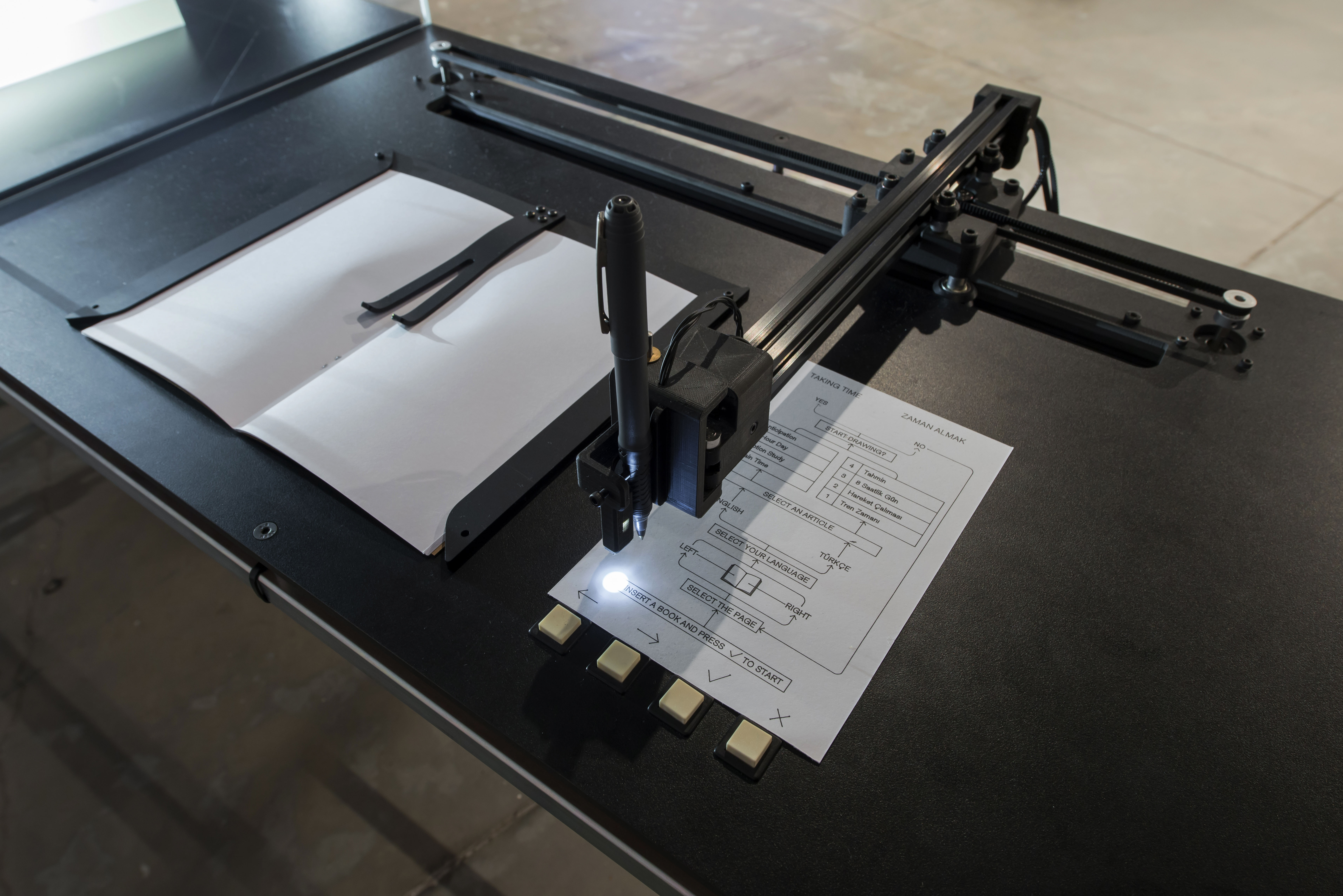

A Commonplace Book. Image © Kayhan Kaygusuz, courtesy of IKSV

That temporal flow is expanded upon at the ‘Time School’ at SALT Galata, which explores the possibilities for manipulating time. The exhibition space is filled with the soft clatter of automated machines from the collective Commonplace Studio, writing Commonplace Books with ballpoint pens. Writing with pens usually carries such a personal touch, but the machines have an eerie uniformity as they dutifully compose their programmed content. I was unsurprised to see a cameo appearance of Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar’s seminal satire, The Time Regulation Institute. At a design exhibition contemplating time in Istanbul, it would be more shocking if it didn’t come up at all.

Image © Kayhan Kaygusuz, courtesy of IKSV

At the Pera Museum’s ‘Scale School’, the interrogation of norms, standards and values somehow comes to encompass a state of constant surveillance, lending an ominous tone to the work. The top floor of the Pera Museum is flooded with light, with the shutters removed from long-closed windows, and the access to the outside world seems to signal an openness. But windows that can be looked out of can also be looked into. Aslı Çiçek, the designer responsible for the open windows, wanted to get rid of the walls, to get the city inside the museum.

Image © Kayhan Kaygusuz, courtesy of IKSV

Mark Henning’s collection of projects careens through various states of paranoia and societal breakdown. There’s a detour through the uncanny valley, that point where humanlike creations or images veer from the trustworthy to the creepy, and an exploration of prosopagnosia, or the inability to distinguish faces, and how that plays into a surveillance state. And yet, as explored in Portraits with Dodgers, to Photograph the Details of a Dark Horse in Low Light – showing Kodak’s push in the 1980s to develop a film that could properly calibrate for darker skin tones – even capturing black faces has been fraught with societal biases. And maybe the ability to give our faces to the computer is a mixed blessing. As one object in the exhibition loudly proclaims: ‘Today’s selfie is tomorrow’s biometric profile.’

Image © Kayhan Kaygusuz, courtesy of IKSV

Andrea Anner and Thibault Brevet of AATB’s piece in the Pera appears, at first, only to consist of two cartoon-like eyes mounted on poles. Eyess Isstanbul, however, is connected to an installation mounted on the roof of the nearby Marmara Pera Hotel, which is visible through the newly opened museum windows. The eyes are programmed to follow the path of the International Space Station – the ISS or Eye SS of the title – while also appearing to peer out over the city itself. Thus we are all surveilled.

It is impossible to escape those eyes, brightly lit and roving over the city, watching all of us live our lives. We are surveilled by the Design Biennial, even as we leave it. The eyes are watching. They are always watching.

_Pera_Museum_School_of_Fluid_Measures_Judith_Seng_420_408_80_c1.jpg)