Imagine this: the sweltering summer heat beats down on unsuspecting Istanbulites. Çay under the shade of balconies does little to abate the humidity, and staying indoors brings misguided moths or malevolent mosquitos. Families and friends journey towards the coastlines for their usual respite: swimming in the Marmara by Istanbul’s most beautiful beach. Except that it is not just one sandy shore. Rather, it is a string of them, dotted along the European and Anatolian coasts. For the city’s modern-day inhabitants, this relief from the unseasonably tropical sun can only be imagined. With many shores closed by the mid-20th century, only beaches in Kilyos, Florya, and the Princes’ Islands now attract those with access to a combination of time, patience and means.

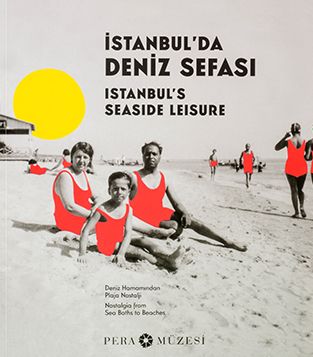

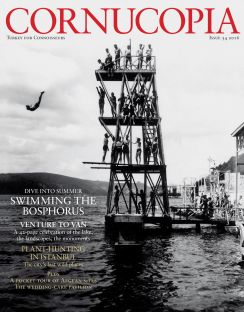

Istanbul’s Seaside Leisure: Nostalgia from Sea Baths to Beaches, currently on display at the Pera Museum, attempts to remedy the loss by offering visitors an opportunity to reminisce about the city’s once-celebrated beaches. The exhibition tickles the senses with music from the 1920s and black-and-white clips of local beachgoers enjoying their weekends. The space is designed with wall panels, an incredible diving tower and a cosy changing closet. These panels and structures are struck in boxes of sand. Beach paraphernalia decorates the space. Elsewhere, visitors can leaf through old magazine covers featuring images of Istanbul beaches. These elements and the refreshing colour palette come together to create a nostalgic but familiar atmosphere of the Istanbul seaside. The vibe is further enlivened by the paintings, illustrations, magazine covers and photographs on display, which narrate vibrant stories from the beaches’ heydays, allowing visitors to live vicariously through them.

With its beautiful imagery, it might surprise visitors to learn that the exhibition’s overarching theme is less concerned with the seaside as a location than it is with the beach culture that emanated from it. It was not by choice that most photographs depicting the sea and beach were from the 1920’s onwards; although photography existed since the late 19th century, the seaside lifestyle only flourished in the early years of the Turkish Republic. The exhibition shows an aspect of the shifting lives of Istanbul residents as the Empire transitioned into a Republic. Much of the era’s guiding principles and priorities can be gleaned from the select works, chiefly in the historical photographs. Despite only capturing a moment in time, many are revealing and dynamic in nature.

The visibility of women throughout the exhibition testifies to the refashioning of norms in the post-Ottoman world. Women were illustrated on the covers of Resimli Ay in chic swimwear. In photographs, many posed with ease and exude an alluring charm and confidence. These are epitomised by the blown-up image of a lady in an exuberant dance pose with one foot tiptoed, the other leg up in an angle and hands thrown in the air. In her stylish beach attire, she unveils the new sense of freedom that Turkish women had acquired. The ladies of Istanbul became beneficiaries of the summer beach culture, going to the seaside to socialize, cooling off in the bracing seawater, playfully burying themselves in the sand, eating ice popsicles, rowing boats and passing time idly.

Istanbul’s Seaside Leisure also reveals women taking charge. The White Russian expats in Istanbul introduced a new way to experience the beach. Melek Celal Sofu, one of the nation’s first female painters, took the opportunity to capture the scenes on canvas. Meanwhile, entrepreneur Süreyya Ilmen capitalised on the lifestyle by converting vegetable gardens on the Anatolian coast into the largest beach in Istanbul, complete with hotels, train and bus stations and top-notch entertainment all summer long. He named Süreyya Beach after himself. Through the seaside and culture that emerged, the Turkish woman represented the young nation’s values of freedom and modernity to the world.

It is unfortunate, therefore, that this narrative is not better foregrounded. In an interview, curator Zefer Toprak spoke about his intentions to subtly recount the history and ideals of the early Republic using Istanbul beach culture as a medium. However, the important role women played in advancing the Istanbul beach culture and representing the ideals of the new country is never hit straight on the head. Each section is seemingly cut off from the others.The subdued approach is found wanting. This leaves the onus on attentive audiences to create the connections concerning women and modernity. With a more direct approach and a stronger arch, the exhibition could be more cohesive and easier for audiences to follow.

Nevertheless, the exhibition thrives in its subtlety. Istanbul’s Seaside Leisure illustrates the beach as a social equaliser. The seaside was akin to the old Ottoman coffeehouses where men from all walks of life could come for coffee and conversation. Here, the shores of Istanbul welcomed all. Anyone (even horses) could gather and partake in the same activities. Despite the growing bourgeoisie class in the early years, the sea was impartial to all. The exhibition delivers the message by setting images of people from across the socioeconomic spectrum next to each other. If not for the headings and subtexts, one might mistake these images as taken from the same beach. It is clear that in the waters of the Marmara and the Bosphorus, wealth became obsolete; only buoyancy and swim strokes were currency.

It is the decision to centre the narrative around Mustafa Kemal Atatürk that drives this notion home. In several sections of the exhibition, audiences are treated to photographs and magazine covers featuring the nation’s beloved leader taking part in various seaside recreations. He is often in an inconspicuous corner surrounded by his peers and younger men and women. The peoples’ proximity to him is notable in these images. Where Ottoman Sultans use to distance themselves from the ruled, Atatürk wanted to be amongst his countrymen, swimming, rowing and relaxing next to them. He wanted to be seen as one of them.

Istanbul’s Seaside Leisure showcases an impressive collection of photographs from the early decades of the Turkish Republic, many of which amaze with their dynamism, humour and honest insight into the lifestyle. It sets itself apart from other historical photography exhibitions by bringing the human element to the forefront. It mostly excels in telling the stories behind these images. In doing so, it creatively reveals little-known narratives about the nation at its infancy. It is almost certain that audiences will leave with nuggets of newfound wisdom, a fresh perspective on the topic or at the very least, a fun day out. As with visits to the beach, audiences will not leave empty-handed from the exhibition. Instead of collecting seashells, visitors can take home perforated sheets with historical facts, snippets from books and even a piece of poetry. These serve as mementoes to for us who will never experience the Istanbul beach culture of the past, but who perhaps appreciate the notions of modernity and freedom it came to represent for modern day Turkey.

_Pera_Museum_School_of_Fluid_Measures_Judith_Seng_420_408_80_c1.jpg)