Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

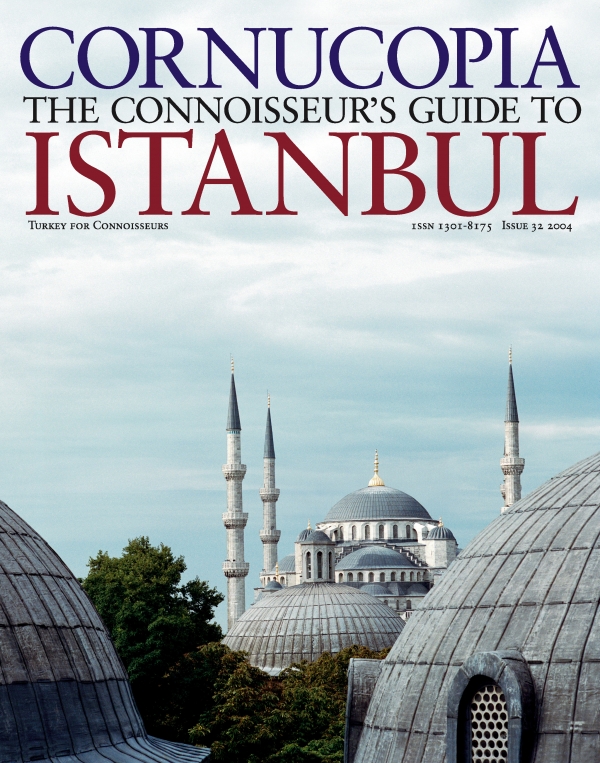

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionJustinian’s soaring edifice inspires the same awe today as it did in visitors a millennium ago who wondered if this were Heaven or Earth. Setting out on a tour of the city’s best-preserved Byzantine churches, Robert Ousterhout still senses an air of the miraculous in Ayasofya

What did historic visitors expect to see when they entered Haghia Sophia, or Ayasofya as it is now known? Many arrived anticipating the miraculous. Like the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, Haghia Sophia – the Church of the Holy Wisdom –has been a thauma (wonder) and a theama (must-see) since its inception. As the Russian ambassadors recounted following their visit in the tenth century, “We knew not if we were in Heaven or on Earth. We only know that God dwells there among men.”

For the Byzantine beholder, Justinian’s Great Church seemed almost beyond human comprehension. Following its completion in ad537, Justinian’s biographer Procopius (c500–c565) breathlessly described it as “wonderful in its beauty yet altogether terrifying by the apparent precariousness of its composition. For it seems somehow not to be raised up in a firm manner, but to soar aloft to the peril of those who are inside.”

In their design for the unique building, the architects Anthemius and Isidorus had consciously emphasised the transcendental, so that the structural elements lose the appearance of support: the solidity of the piers vanishes behind lavish coverings; colonnades become mere decorative screens. Even the carved marble details seem dematerialised: with their delicate, lace-like surfaces, the capitals appear unable to support anything of substance.

The sense of weightlessness, despite the great mass of the building, led Procopius to conclude that the great dome was not supported from below but suspended by a golden chain from heaven. Like the Russian ambassadors, Procopius emphasised the sanctity of the interior space: “Whenever anyone enters to pray, he understands at once that it is not by human power and skill, but by God’s will that this work has been so finely finished. His mind is lifted up to God and floats on air, feeling that God cannot be far away, but must especially love to dwell in this place, which He has chosen.”

Similar themes echo throughout the Byzantine period, as for example in the semi-legendary Narrative of Haghia Sophia, which tells that the bricks of the building were stamped with the verses of Psalm 45, “God is in her midst, she shall not be moved”, and that the plan was given to the emperor by an angel. Probably first written in the ninth century, the Narrative proved to be the most popular and the most enduring of the numerous writings concerning the history of the building; it was translated into Latin, medieval Russian, Ottoman Turkish, Persian and modern Greek, and it forms the basis of almost all later “legendary” discussions of the building. Elements of the Narrative have found their way into visitors’ accounts of the capital, ranging from medieval Russian pilgrims to modern-day tourists. A Greek copy prepared at the behest of Mehmed the Conqueror in 1474 is among the surviving imperial manuscripts in the Topkapı Palace.

Popular though it might have been, the Narrative is notoriously inaccurate. For example, the old church had been destroyed in the Nike Riots of 532, and although the riots are mentioned in the text, we are told that it was Justinian’s decision to tear down the church and rebuild it. In addition, it gives the name of the architect as Ignatius, not Anthemius or Isidorus. The text also places the collapse of the first dome after Justinian’s death, not before, and names the same Ignatius as the architect of its rebuilding. Moreover, Ignatius blames the failure of the first dome on its height and is claimed to have rebuilt it with a lower profile – the exact opposite of what actually happened. In spite of such errors, at its simplest level the Narrative is full of great stories that are still repeated by tour guides, textbooks and university lecturers. For example, I still find it difficult to discuss the sixth-century construction without relating how Justinian is said to have exclaimed, “Solomon, I have vanquished thee!” at the dedication.

The popular story of the guardian angel and the mason’s apprentice appears for the first time here as well: a mysterious messenger arrives while the workers are away; he sends the apprentice to find the emperor, assuring him that he will watch over the building until the boy returns; Justinian realises the messenger is angelic, and exiles the apprentice so that he can never return, thus guaranteeing permanent divine protection for the church.

I’m also particularly fascinated by the curious construction details, such as the recipe for the mortar, which includes the juice of boiled barley in place of water to make it sticky, as well as the insertion of relics into every 12th course of bricks. And modern scientists have found it necessary to test the alleged properties of the lightweight bricks from Rhodes that the text claims were employed in the construction.

These legends continue to be repeated because they reflect some basic truths, if not about the building, at least about the perceptions of it. As Constantinople shrank from the large scale of the Early Christian centuries to the small scale of the medieval centuries, the city lost contact with its past. What had been carefully written as history following in the classical tradition became the stuff of myth and legend in the subsequent period. It is not surprising that the construction of a building as ambitious as that of Haghia Sophia was a source of wonder to the ninth-century writer. The suggestion that it was built by one hundred teams of one hundred workers (that is, 10,000 workers), each led by a master mason, may overstate the actual size of the sixth-century workforce, but it provides the necessary contrast to the small buildings constructed by small workshops more familiar to the writer. While we may quibble with the facts as presented in the Narrative, there is nevertheless an element of truth to it.

Not only the building, but also its mosaic decoration came to be regarded as miraculous. Surprisingly, the sixth-century decorative programme contained no figural mosaics, but the building had been dedicated to a concept – the Holy Wisdom – not to a person. The architecture with its geometric complexity is best understood in conceptual terms, and the mosaic decoration was subordinate to the grand architectural gesture.

After the end of the Iconoclast Controversy in 843, however, images were gradually added. After all, Haghia Sophia was the greatest showcase of the Byzantine empire, and as the church was associated with both the emperor and the patriarch, it was important for the building to project official policy. The Synodikon of Orthodoxy had emphasised the appropriateness and necessity of religious images in Orthodox worship. What better place to display them than Haghia Sophia?

The building fulfilled a unique function within Byzantine society, and its decoration needed to project Orthodox belief while emphasising its position at the heart of the empire. Because of its immensity, however, images had to be really big to be noticed at all; moreover, because of the height of the vaults, extensive and expensive scaffoldings were needed for the artisans to work. Not surprisingly, mosaics were added only gradually and in select locations.

Figural decoration began with the apse, into which a great mosaic of the enthroned Virgin and Child was inserted. The figures were cut into the pre-existing gold ground, with archangels placed on the vault to either side. The Virgin here is close to five metres tall but nevertheless dwarfed by the space. In the sermon he delivered at the dedication of the apse mosaic, at Easter 867, the Patriarch Photius emphasised a direct relationship between icons and the Incarnation of Christ. That Christ allowed his sanctity to be “represented” in the flesh was the greatest justification for the representation of holy figures in icons. For Photius, the equation could work both ways; as he explained, “Christ was born in the flesh and is carried in the arms of his mother. This is seen, proven and demonstrated by icons.” For the Byzantines, an image of the Virgin and Child was never just a picture – it was a statement of Orthodox theology and a proclamation of the efficacy of icons. The image in the apse of Haghia Sophia stands as one of the most revered and most often repeated of all iconic formulae.

Photius’s dedicatory sermon concluded with the suggestion that this was to be the first of many images to be added to Haghia Sophia: “Grant to those whom you have made emperors on Earth to consecrate the remainder of the church with holy images.” We may assume that at more or less the same time an image of Christ Pantokrator was inserted at the crown of the dome, as well as other images, now lost but known from texts or drawings: saints, archangels, major and minor prophets, church fathers (a few still preserved), metrical inscriptions, and narrative scenes from the life of Christ.

The recently uncovered seraph in the northeast pendentive was part of the last phase of decoration after the reconstruction of the dome in the mid-14th century. The totality did not quite match the standard Byzantine church programme, but the mosaics infused Haghia Sophia with potent, recognisable images – and emphasised the role of images in Orthodox devotion.

With the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, Fatih Mehmed converted Haghia Sophia to a mosque as his first official act. The conversion involved minimal physical transformation, and even its name remained the same – Ayasofya Camii in Turkish. A minaret was constructed, a mihrab was added; Islamic relics and Ottoman battle trophies were displayed. But for the Christians after this time – both European and Orthodox – Haghia Sophia became a sort of Wailing Wall, the bearer of historical memory, of a lost heritage and a vanished civilisation.

With the Ottoman conversion, the building continued to accrue legends and stories of miracles. For example, that when the dome collapsed on the day of the Prophet Mohammed’s birth, it could only be repaired with a special mortar made of sand from Mecca and water from the well of Zemzem. Similarly, that reciting the opening sura of the Koran before the doors of Ayasofya, which were said to be made from the wood of Noah’s Ark, could guarantee a safe voyage. And water from both the sacred well and a sweating column were claimed to have curative powers. Even while a mosque, the building was still regarded as miraculous, by both Muslims and Christians.

Until the early 18th century, visitors to Ayasofya could still see figural mosaics on the walls and vaults. The earliest illustrated account by Guillaume-Joseph Grelot recorded what he saw in situ in 1672: seraphim in the pendentives; standing figures in the eastern arch; the Virgin in the apse; archangels in the vault to either side; and what he calls the “Holy Face on the Veil of Veronica” at the crown of the bema vault. Here he must have been referring to the Mandylion, the face of Christ miraculously imprinted on a handkerchief – a relic once housed in the Great Palace.

No other visitors mention this image, however, and when the Byzantine Institute of America uncovered the mosaics in the 1930s they found only a solid field of gold tesserae where the Mandylion should have been. What Grelot saw was at best a figment of his imagination: a miraculous image that wasn’t there. Or was it a miracle? Could Grelot have witnessed the miraculous appearance of a miraculous image inside a miraculous building?

Robert Ousterhout teaches Byzantine art and architecture at the University of Pennsylvania. His book ‘A Byzantine Settlement in Cappadocia’ appeared in a second, revised edition in 2011

Also see ‘Building Wonders’ a US documentary on the Ayasofya with contributions by Robert Ousterhout

From a trusty staple to the stuff of feasts, beans are at the very heart of Turkish cuisine. How did we ever live without them?

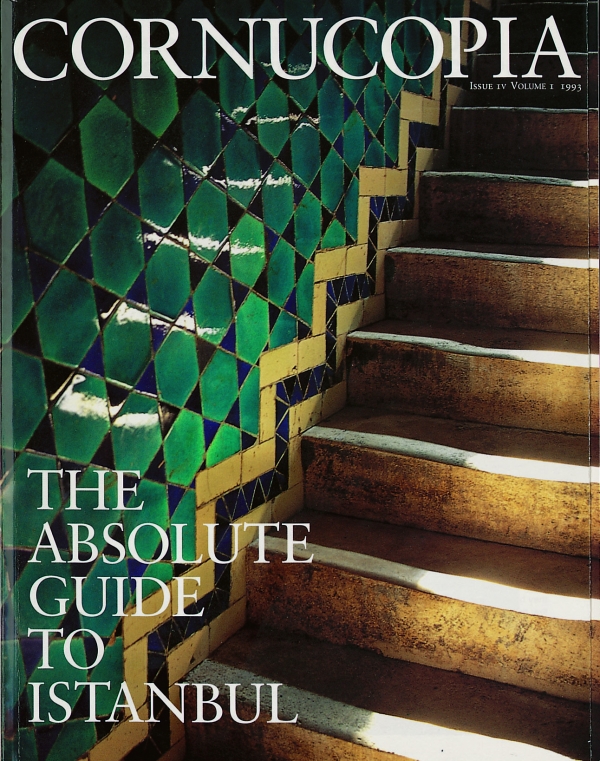

In a vivid, impressionistic portrait of the Byzantine city, Robert Ousterhout uncovers the history of Byzantium in ten objects, explores the soaring edifice of Ayasofya and picks four of the city’s most inspiring smaller churches.

Take in the Topkapı, where the sultans held sway in secluded grandeur. Saunter round Sultanahmet and the Hippodrome: make the most of the mosques, monuments and museums. Get the buzz of the bazaar: where to snap up covetable collectables and cheerful bargains

Deep in the industrial outskirts of Istanbul, Griselda Warr enters an Aladdin’s cave of Anatolian treasures. Photographs by Fritz von der Schulenburg

AyşeDeniz Gökçin’s musical creations combine the rock-star appeal of Franz Liszt and the psychedelic/progressive brilliance of the band Pink Floyd. Tony Barrell found this prodigiously talented young pianist a force to be reckoned with. Photograph by Charles Hopkinson

John Carswell solves the mystery of the ‘lemon squeezer’ that wasn’t

In a decade of monitoring Turkey’s burgeoning wine industry, Kevin Gould has never been more impressed. He and the Cornucopia tasting team enthusiastically sampled this year’s top bottles and nominated their favourites

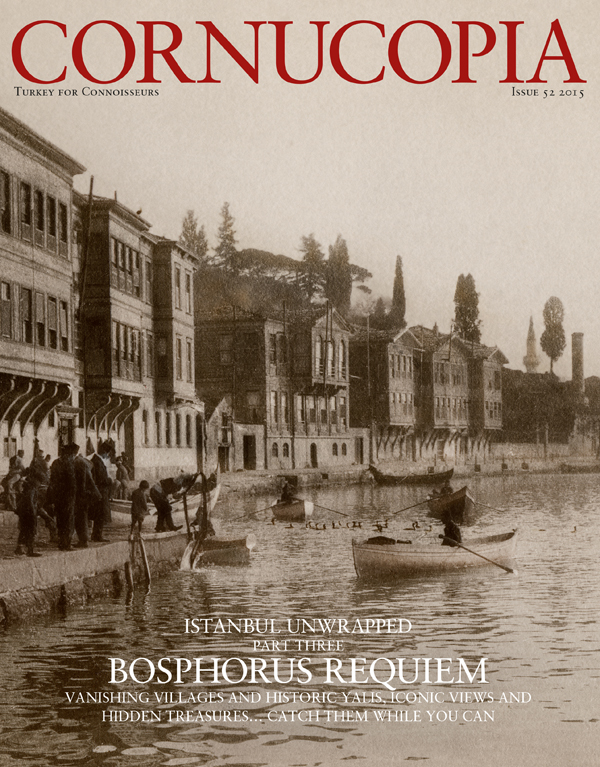

It is a joy to explore. New universities, a new museum, and a growing band of new aficionados who have invested modest means in old houses, have created a wonderful sense of optimism. But the ancient waterfront is in the eye of the storm, with many quarters due to be bulldozed and the threat of a hideous new marina. Enjoy it while you can

Give yourself over to the grit and bustle of Eminönü’s waterside markets, then ascend to Sinan’s sublime hilltop mosques – the awesome Süleymaniye and the haunting Şehzade. In their shadow is the exuberantly tiles Rüstem Pasha Mosque. Cornucopia devotes 24 pages to this vibrant area, with features on Eminönü and the Suleymaniye district with photographs by Jürgen Frank, and a guide to the mosques beautifully depicted by Fritz von der Schulenburg

Hidden away in one of Istanbul’s least prepossessing neighbourhoods is a walled garden surrounding a dream of a kiosk – a favourite of many sultans.

Within the deepest reaches of the palace lies the very seat of the sultans’ power

The Grand Bazaar: From Iznik to Armani, objets d’art to handloomed carpets: the choice is yours

When David Wheeler set out to satisfy his craving to explore Turkish gardens, he was guided by a diverse cast of committed Istanbul citizens. What he discovered were myriad horticultural havens, from Byzantine market gardens to Ottoman cemeteries – many of them under imminent threat.

SPECIAL OFFER: order five beautiful garden-themed issues, including this one, for only £80. List price £122

In his 40-year career, Sinan (1489–1588) transformed the Istanbul skyline. Here we explore three of the chief imperial architect’s masterpieces from the golden age of Süleyman the Magnificent. Photographs by Fritz von der Schulenburg

The long-awaited Naval Museum has many wonders to reveal, but nothing to compare with the fabulously ornate imperial barges

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now