Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionA new book on Vassilaki Kargopoulo: Photographer to His Majesty the Sultan. By Philip Mansel

From the time of its invention, photography had a particular appeal for royalty: dynasties found it a new and unusually effective weapon in their constant efforts – as old as monarchy itself – to propagate their own image. For the dynasties of the Middle East, photography had the added advantage of propagating an image of dignified modernity. It could also help them see what distant, unvisited corners of their domains looked like.

In the autumn of 1839, only a few months after the first public demonstration of the new art form in Paris, French photographers gave Kavalali Mehmed Ali Pasha a private view in Alexandria. Within a short while, professional photographers had established studios in Cairo and Constantinople, and the Ottoman Sultans and Caliphs of all the Muslims were employing their own court photographers, just like their fellow-monarchs in Western Europe.

Bahattin Öztuncay’s new book, Vassilaki Kargopoulo: Photographer to His Majesty the Sultan, is devoted to one such photographer, an Ottoman Greek who opened a studio in Beyoglu, near the Russian embassy, in 1850.

Many Greeks were employed in the service of Sultan Abdülhamid II: for example, his doctor, Spiridion Mavroyennis, and his foreign minister, Alexander Karatheodory. In 1879 Vassilaki (or Basile) Kargopoulo was appointed Photographe de Sa Majesté Impériale le Sultan, with the right to display the Sultan’s tugra, or monogram, on his business card.

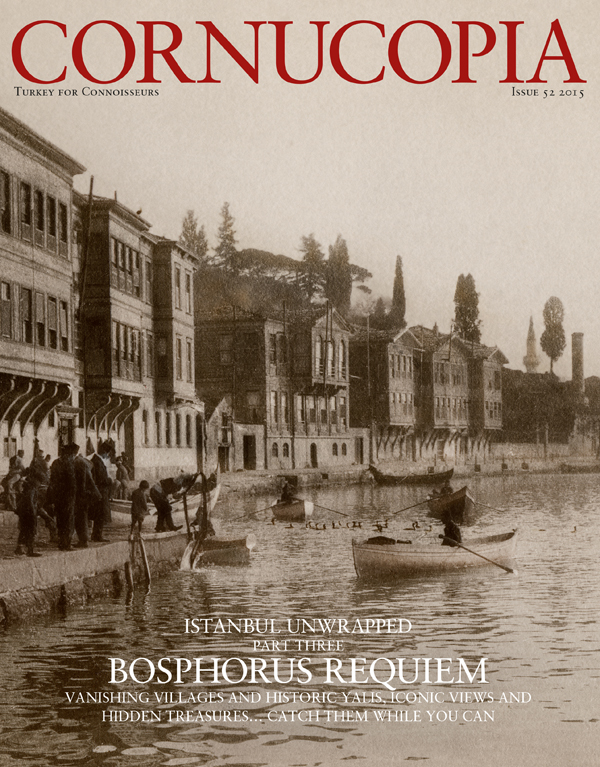

Over the next few years he created a unique visual record of the Ottoman Empire in its last years of glory. His subjects included Gazi Osman Pasha, defender of Plevna against the Russians in 1877; princes (including the future sultans Mehmed V and VI, as beardless young men); princesses; mevlevi and Bektashi sheikhs; the Bulgarian Exarch and the Orthodox Patriarch; street sellers; palace interiors and views of the Bosphorus, including what would appear to be the entire Ottoman fleet, moored off Büyükdere. Unlike his predecessors and sucessors, however, Abdülhamid II, for reasons best known to himself, was not photographed. He may have considered it inappropriate for the Caliph.

When Kargopoulo died of a heart attack, two months after receiving a gold medal for fine arts on January 29, 1886, he was succeeded as court photographer by his son, Konstantin Kargopoulo. In the mysterious ways of the Yildiz Palace, however, Konstantin lost the job in 1888. In 1895 the studio in Beyoglu was closed and the family went to live in Aydin.

Bahettin Öztuncay is an expert on nineteenth-century photography in the Ottoman Empire who has already written on two even earlier photographers of Constantinople from the 1850s: James Robertson and Ernest de Caranza. His latest work contains not only 259 old photographs but also a detailed discussion of the technical processes of photography as practised in Constantinople. It will delight all those who feel the wistful charm of the Ottoman Empire in the age of the fez and the stambouline.

Philip Mansel

For more than thirty years Terence Mitford and George Bean painstakingly identified and recorded the forgotten ancient sites of Turkey’s Aegean and southern shores. Their contribution to the preservation of the country’s archaeological heritage is incalculable, their guidebooks are legendary, yet the men themselves are unsung. Barnaby Rogerson, in this homage to his heroes, uncovers an extraordinary pair: a gentle giant and a man of steel

The dusty rooms of a crumbling Istanbul palazzo are a living museum of the plaster-caster’s art. Berrin Torolsan visits the heir to a fine tradition. Photographs by Fritz von der Schuelnburg

Dedicated to Venus by the Romans, no other fruit has so many symbolic and material associations with sensual beauty. Lovely soft pink flowers are followed by crimson velvetly fruit, soft and round, with a heavenly taste and aroma.

More cookery features

William Morris and Mariano Fortuny familiarlised the West with the sumptuous floral designs of Ottoman textiles. But few are aware of the the bolder side of Turkish design

The intoxicating scent of attar of roses, the oil distilled from the petals of damask roses, has worked its magic on men and women for centuries. Martyn Rix traces the history of the damask rose from its roots in Neolithic times and travels to Isparta in southwest Anatolia to see how these precious petals yield up a liquid worth its weight in gold

Few travellers to Turkey enjoying the hedonistic delights of Mediterranean cruising venture east of Antalya, capital of Anatolia’s Turquoise Coast – intimidated perhaps by rumours of a wild hinterland that even Alexander the Great found hard to tame. But those who dare to leave the crowds behind will discover an awe-inspiring landscape of cliffs that drop sheer to the sea, epic castles and remote Byzantine retreats. Kate Clow and Jacqueline de Gier joined ten other guests and a lecturer for a twelve-day voyage of enlightenment aboard a traditional gulet

Geoffrey Lewis, acknowledged as the dean of Turkish studies in Britain and beyond, learned the language while serving in the RAF in Egypt. When he finally visited Turkey, he was smitten for good. By Andrew Mango. Portrait by Charles Hopkinson

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now