Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionSubscribers can read the illustrated version of this article online in the digital edition of Cornucopia 62

Elizabeth Rodini’s thoughtful account traces the circuitous journey made by the portrait of Mehmed the Conqueror by Gentile Bellini that now belongs to the National Gallery in London (above right). Across 400 years it has travelled from Istanbul to London and, temporarily, back again to Istanbul, with stays in Venice and elsewhere.

The book fortuitously coincides with the Istanbul Municipality’s purchase of a related picture (right) in June 2020. Istanbul’s acquisition portrays two people, one based on Gentile’s image of Mehmed (though it is uncertain whether the National Gallery’s portrait was the sole source or whether other images were involved).

Rodini’s methods will be useful tools for excavating the Istanbul work’s probably very different history. It is unlikely, however, that its story willbe as rich or colourful as the one she tells about the London portrait. Rodini first saw the portrait in 2003, when it was stored with problematic paintings in the basement of the National Gallery. In this context its defects were obvious. The figure of Mehmed was almost entirely repainted: “his face hazy and his form lost under a bundle of ill-fitting clothes”. The absence of Gentile’s characteristic linear precision raised doubts that this was the portrait he painted in Istanbul in 1480. Gentile’s “sharp edge of observation” was visible in the painted frame and textile ledge-cover, however, and modern imaging technology proved that the current surface follows Gentile’s outlines for the figure and the inscription, affirming the picture’s identity.

In 2008 it was transferred to the Victoria and Albert Museum and hung in a gallery dedicated to cross-cultural exchange, which emphasised its value as a historical document.

Believing that Gentile’s artistry had been worn away as the painting moved in space and time, Rodini set out to tell the story of this journey. Because evidence is missing for some of its stops, she explored their historical contexts. She explains her methodology in detail and recognises that she became personally immersed in sometimes wandering side-trips.

Her account of the portrait’s creation in Istanbul moves quickly through the facts. Responding to the Sultan Mehmed’s request for a skilled portraitist during critical peace negotiations in 1479, the Venetian senate rapidly dispatched their state painter.

Gentile was a valuable diplomatic gift, bringing his abilities to glorify the Sultan and his power in the most up-to-date European style. He produced a profile bust on undated bronze medals – or at least a drawing for it – and a nearly life-sized, slightly turned, painted bust that conveyed a more convincing presence.

Gentile also took with him an album of drawings on vellum by his late father, Jacopo, intended as a tool for study and teaching. It reflected current Venetian concerns: the realistic depiction of people and animals, narrative composition and, above all, carefully demarcated space and perspective.

Rodini emphasises that Gentile acquired rare access to private spaces in Topkapı Palace, where he engaged with Mehmed, examining and probably discussing objects in the royal treasury and Jacopo’s sketchbook, and studying people who attracted Mehmed’s attention. Rodini sites Gentile’s surviving drawings of the

latter as evidence of his access to the court and exposure to Oriental art there.

Her analysis of the resulting effects of these encounters on Gentile’s painting skirts around the discrepancy between what Mehmed probably valued in Gentile’s art and what remains of Gentile’s painting itself.

A page from Mehmed’s own youthful sketchbook in the Topkapı (above right) is evidence of the Sultan’s interest in verisimilitude and linear description.

Gentile’s paintings in Venice show his sharp delineation, even transcription of surfaces and unselective topographical approach to composition. This was his version of the Venetian “eyewitness” style and testifies to his work’s truthfulness. Rodini contends that Mehmed wanted Gentile’s portrait to demonstrate an Italian art form, not what a Turk actually looked like. Yet we do not know how Mehmed intended to use the work or whether he was satisfied with it, because he dismissed Gentile shortly after the date on the painting and died soon thereafter.

After those events in 1481, the historical record ceases until the picture is documented in Venice in 1865. For religious reasons, Mehmed’s successor, Bayezid II, reportedly sent all of his father’s paintings to the bazaar, where Gentile’s portrait may have been purchased by a Venetian merchant or traveller. An unverifiable report published in 1648 mentions that the portrait (supposedly brought back by Gentile himself) was in the home of Pietro Zen.

Rodini uses the Zens as stand-ins for likely owners in the Venetian cultural context: a rich mercantile family who would display Gentile’s painting in their palazzo’s portego, or reception hall, to be admired by visitors. It was little known to the public, however.

Rodini disproves the humanist Paolo Giovio’s claim that the image of Mehmed in his famous portrait collection, installed in his villa in Como during the 1540s and illustrated in a publication of 1575 (below left), was copied from Gentile’s. In 1578, when Ottoman officials sought reliable models for an illustrated history of the sultans from the Venetian government, none could be found. To save the city’s reputation as an art repository, the Senate had the workshop of Paolo Veronese create a set.

The acquisition of Gentile’s portrait in 1865 by the British archaeologist and diplomat Austin Henry Layard most engages Rodini. She takes us to his excavations of Mesopotamian antiquities, his chance purchase of the Gentile in Venice, the display of his antiquities and paintings in London, visits to the sultan at Topkapı as British ambassador, and his retirement in Venice, where he transferred his collection. She describes Layard admiring Gentile’s painting on an easel in the main hall of his palace – just where the Zens might have placed it – and seeing something of himself in the artist’s travels and experiences in Istanbul.

Layard had the canvas relined and its surface “treated” twice to improve its appearance. Despite obvious differences, he linked his image with Paolo Giovio’s in order to give it an old provenance that would give it higher priority than other (unspecified) portraits of Mehmed which had no history. Rodini cites another painting, now in Doha, Qatar, to show that Gentile’s painting had become an authoritative prototype by about 1510.

The Istanbul Municipality’s probably earlier (and less faded?) double portrait should be considered in this context. Rodini turns to legal documents to land Gentile’s portrait in the National Gallery in London. Layard had willed “all [his] pictures (except portraits)” to the gallery. Over the five years following the death of his widow, Enid, a series of obstacles were resolved through hair-splitting debates over the meaning of terms: “art”, “history”, “heirloom” and, finally, “portrait”.

Rodini concludes with an insightful discussion of the painting’s recent “afterlives” in Istanbul. In 1999 a commercial bank negotiated its brief loan for an exhibition commemorating the 700th anniversary of the Ottoman Empire. Over 30,000 came to visit the Conqueror, seen to embody Ottoman history and much of Turkish identity. The presence of the famous Venetian portrait seemed to augur a new Golden Age, in which Turkey could hold its own in relation to European civilisation.

Gentile’s painting soon returned to Istanbul for a larger exhibition at the Topkapı in 2000, celebrating its contribution to the tradition of Ottoman imperial portraiture. These expressions of cultural pride coincided with the launch of Turkey’s candidacy for the European Union.

When Rodini visited Istanbul in 2018, opinion of Gentile’s image had changed, along with failing hopes of joining the EU and rising nationalism. Nostalgia for the illustrious past and traditional values had led to a “Neo-Ottomanism”. Visual symbols asserted faith, independence and strong rule: headscarves, the revival of Ottoman institutional names and architectural styles, and state-supported restoration of Ottoman monuments. Rodini caps her journey at Istanbul’s new Panorama 1453 History Museum outside the city walls, where a huge photo of the

head of Gentile’s Fatih is poised at the entrance to witness a re-enactment of his victory.

Rosamond E Mack is an art historian best known for her book ‘Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300–1600’

● For Gentile Bellini’s Istanbul drawings, see ‘A Bellini for the Sultan’ by Rosamond E Mack

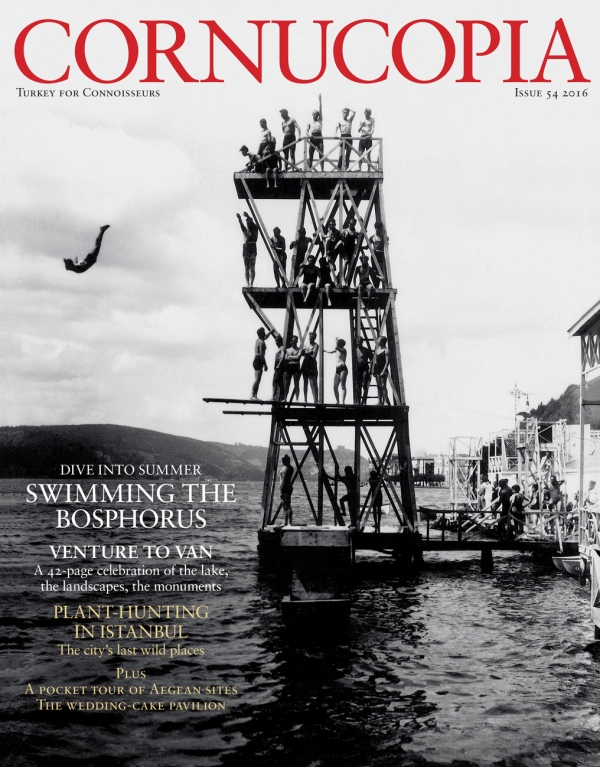

in Cornucopia 54

Tim Stanley on a celebration of Şeyh Hamdullah and the 500-year-old calligraphy tradition that almost vanished

A newly discovered 16th-century painting of Süleyman the Magnificent, sold by Sotheby’s London this spring (and subseqently donated to the Istanbul Municipality by an anonymous businessman), is the most ‘immediate’ portrait of him until the last years of his life. This is Süleyman in his pomp. By Julian Raby

An affectionate tribute to Suna Kıraç by Özalp Birol

Fruit poached to perfection, the fragrant ‘hoşaf’, or compote, is a simple, soothing finale to any meal

Berrin Torolsan is enchanted by the House of Hindliyan. Photographs by Tim Beddow

Philip Mansel on a book that tells the story of the Pera-born dragoman Mouradgea d’Ohsson, the ultimate cosmopolite who lifted the lid on the Topkapı. This special 24-page feature, Cornucopia includes 28 of the images from Mouradgea’s magnum opus, Tableau général de l’Empire othoman

Anatolia on foot 40 years ago, by Christopher Trillo, with photographs by the author and Stephen Scoffham

Central Asia, a plant-hunter’s paradise, has long held Chris Gardner under its spell. For two decades the Antalya-based botanical writer and photographer has traversed countless miles of steppe and mountain in search of the hardier cousins of many of his favourite Turkish plants

Caroline Eden tells Ergun Çağatay’s remarkable story

John Hare on how the two-humped wild camel was saved from extinction

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now