Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionParis has its Versailles, St Petersburg its Hermitage, but both palaces served for a mere twinkling of the eye compared with the Topkapı, residence of the Ottoman sultans for some 400 years. Dolmabahçe, the wedding-cake structure that replaced it in 1853, is the embodiment of imperial pretension, but the Topkapı still preserves the memory of a military encampment. It is not one grand edifice but a complex of buildings and kiosks arranged in a series of adjacent courtyards that appear designed to preserve the privacy and mystery of the royal household. But the palace is no Alhambra. The architecture is masculine, unadorned and lacking in vertical impact, and it takes time, and a knowledge of its working life, to absorb its immensity.

Only when you look back at the skyline on the ferry home do you realise how all the parts, built piecemeal over time, combine to form a majestic whole. Mehmet the Conqueror began building the palace, not directly after the conquest in 1453 but six years later. He had just finished a vast palace overlooking the Golden Horn, where Istanbul University now stands, when he started all over again with the Topkapı. What prompted him? Perhaps a campaign to Athens inspired him to build on the site, which had been the ancient acropolis in the centuries before Constantine. Or perhaps he recognised that the promontory the palace occupies was the most remarkable piece of real estate he owned. The building was finally turned into a museum in 1924 after Turkey became a republic.

Allow yourself time to wander through the carriage rooms, the gardens and the kitchens, which contain the priceless Chinese blue-and-white tableware. To see the famous Topkapı dagger, you have to buy a separate ticket, but the real shock is that its diamonds and emeralds seem as paste next to the rest of the collection. You need an extra ticket, too, for the harem – there used to be a half-hour guided tour but you can now wander at leisure. You get to see only the tip of the iceberg of the royal apartments, but it is essential viewing. Cornucopia 29 has a 24-page photo feature on the intriguing Black Eunuchs’ Quarters, to which Cornucopia was granted rare access before its recent opening to the public.

Not everyone is thrilled with changes at the Topkapı. Moves to jazz things up have led to too much gold leaf – especially on the stunning tiles of the façade of the Circumcision Chamber. The Treasury has been reduced to an incoherent display in spotlit cases worthy of Bond Street. It excites the eye but not the intellect.

But the gardens are still the perfect place to take a siesta. To enjoy your visit, take your time, bring a book. The Konyalı restaurant has sadly gone down hill, and wine has recently been forbidden, but the Karakol Restaurant just outside the museum is perfectly decent. The best book on the palace, Architecture, Ceremonial and Power by Gülru Necipoğlu, is sadly out of print, but Claire Karaz’s slim volume Topkapı Palace: Inside and Out is a handy guide.

Mehmed II started building the Topkapı, on the site of the old Byzantine acropolis overlooking the Golden Horn and the Sea of Marmara, in 1459, sixe years after his conquest of Constantinople. Known as the New Palace until the 19th century, when it acquired the name of Topkapı (Cannon Gate), it is not a palace in the traditional European sense but a complex of low buildings and pavilions, kiosks and courtyards, to which Mehmed II’s successors continued to add.

For almost 400 years it was the principal residence of the Ottoman sultans, as well as the seat of government and setting for state occasions and royal entertainments. It was a self-contained city that most of the inhabitants rarely left.

In his 1844 book Three Years in Constantinople, Charles White, later correspondent of The Daily Telegraph, describes a chance encounter on the Galata Bridge with the Queen Mother as she was returning from Friday prayers in Eyüp on the Golden Horn to her palace on the Bosphorus. “In a richly ornamented, fourteen-oared imperial boat,” the Valida was seated “upon embroidered cushions, placed on a purple velvet carpet, fringed with gold… As the kayik glided beneath our feet, we uncovered our heads. The Valida, who is well acquainted with European forms of respect, instantly raised her eyes and returned our intended mark of deference with that fixed and penetrating gaze, which is the customary token of imperial recognition…”

In this gilded flotilla, the 38-year-old mother of the reigning Ottoman sultan, Abdülmecid, was accompanied on her sumptuous barge by ladies-in-waiting and three handsome lalas, or black eunuchs: “two occupied the after-deck… a third sat at the bow”. Five smaller boats followed; in the first was the Chief Black Eunuch with his two deputies and two “youthful Lalas”, one of whom held a crimson umbrella over his head. The other boats each carried seven ladies-in-waiting, “a Pleiades of youth and beauty”, attended by two black agas with large umbrellas to protect their precious cargo from sun and wind. On land, White adds, the procession would follow the same etiquette, with the Queen Mother’s black eunuchs accompanying her on horseback.

Ottoman harem tales fascinated Western writers, composers and artists. White romantically described a “galaxy of houris” peppered with guardian angels, the black eunuchs. It was graphically colourful and sensually piquant. At the Topkapı, people still queue to see the Harem, though most of its chambers and courtyards remain out of bounds, including the Black Eunuchs’ Dormitories.

But things are gradually changing, as parts of the Topkapı’s collection are moved out to ancillary buildings in the palace grounds, such as the old imperial mint, and the focus of attention on the palace itself turns to the architecture.

There is no mention of eunuchs at the Ottoman court before Mehmed the Conqueror conquered the Byzantine capital in 1453. But Byzantium had a huge caste of eunuch functionaries. When the Conqueror welcomed Byzantium’s aristocrats at court, eunuchs were one of the institutions they introduced. There was an ancient practice of taking fair young Russian, Albanian, German and Slav boys (from which the word “slave” derives) as war booty to be sold to Middle Eastern and Asian courts. Castrated slaves fetched the best prices. The bright and talented among them had spectacular careers: the hadım (castrati), as the Ottomans knew them, included generals, provincial governors and at least five grand viziers, who proudly bore the title Hadım before their names.

In 1513, ten white and ten black eunuchs are recorded at the Topkapı. The ak ağa, or white agas, part of the Privy Chamber, ran the School of Pages and Harem School on strict monastic, hierarchical lines. How desirable the post became is illustrated by the Venetian-born Gazanfer Ağa, who had himself and his brother castrated to be able to enter the service of the Grand Turk. His brother died, but Gazanfer’s 30-year career saw him become chief white eunuch and one of the most powerful men in the late 16th century, the golden age of the white eunuchs. When Murad III, grandson of Süleyman the Magnificent, appointed the Abyssinian Habesh Mehmed Ağa superintendent of the Harem, power shifted from white agas to black, and kara ağa (black agas) began to run the ever-more-influential Harem. The brilliant would gain unrivalled influence in affairs of state. Who were these formidable black eunuchs, responsible for 300 years for the House of Osman’s Harem?

Ebony-skinned Sudanese or “chocolate-coloured” Ethiopian boys, captured by rival clans or sold by parents to Jewish slave dealers, were brought to Upper Egypt to undergo surgical operation by Coptic monks (castration was part of their own tradition). The best-looking boys were offered to the Ottoman palace. There, given the names of precious stones or flowers – Diamond, Ruby, Amber, Coral, Hyacinth, Jasmine and Carnation were common – they learnt Turkish, arithmetic, literature, languages, calligraphy, sports and, above all, etiquette. From menial domestic duties, novices rose to be guards, secretaries, tutors to princes, chamberlains to sultans’ mothers, wives and sisters, orchestrators of festivities, treasurers and statesmen.

By the 1700s chief black eunuchs ranked second to grand viziers and were amassing enormous wealth. Many, like the great Haji Beshir Aga, spent fortunes on charity, commissioning mosques, schools, public baths, libraries, caravanserais and fountains. Many paid with their lives in political intrigues.

The Carriage Gate by the Divan (Council Chamber), used for outings by Harem women, conceals a domed chamber tiled with images of slender cypresses. Once guarded by a pair of black novice agas, it leads to the pebble-paved Courtyard of the Black Eunuchs. Facing the Divan’s massive rear walls is the tiled façade of the black eunuchs’ simple dormitories. A plaque over the door announcing “All believers are brothers” is dated 1668 (much of the Harem had been gutted by a great fire in 1662). Next to them is the residence of the chief black eunuch, with its hamam, guestrooms and, upstairs, the crown princes’ classrooms, decorated in Rococo style.

Once accustomed to the dimness inside, you become aware of a long, narrow courtyard, lit from vaults high above, with a monumental fireplace at the far end, its tiled hood reaching to the second floor. The head black porter, the kapı ağası, had his quarters here – five adjoining chambers with windows into inner and outer courtyards, the terracotta-tiled floors of the chambers once covered with fine Egyptian mats and rugs. Low seating with plenty of cushions ran around the rooms. A patchwork of 16th- and 17th-century tiles, recycled after the fire, some quite exquisite, covers the walls. Across the courtyard were storage rooms and cells for novices.

Stairs facing the entrance lead to the chambers of higher-ranking agas, reached from the colonnaded courtyard. Each has a paned lantern window by the door. The walls are finely painted or stencilled with flowers in washes of powder pink, sage green and sky blue. Delicate tendrils frame seascapes, like vignettes in poetry books.

Upstairs are marble lavatories, and rooms for novices, again with views of imagined seashores. Retired eunuchs also had apartments on this floor. Panelled doors lean out from the wall to form a ladder to a bedchamber upstairs, with a splendid wardrobe for bedding. Braziers of embers from the great fireplace would easily heat these shipshape rooms. Up yet more stairs is the great archive room, where the Harem treasury ledgers were maintained.

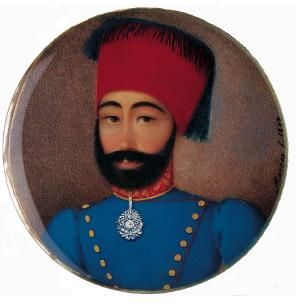

Black eunuchs were famed for their longevity and often retired with pensions to Egypt. Fellow agas would donate three months’ salary when one of their number went back out into the world. Some would stay on to help younger comrades. It is easy to imagine what awesome figures they struck in towering turban and silks, with a jewelled dagger in a crimson sash. When Mahmud II curtailed slavery, and the frock coat and fez replaced the kaftan and turban, it was the end of their heyday. Even if they had lost nothing of their noble bearing, by the time the sultan moved to Dolmabahçe Palace in the 1850s, the black agas, once the inspiration for Mozart’s Osmin in Die Entführung aus dem Serail, had been reduced to imposing escorts for parties of Harem ladies – as they were when Charles White observed the Valida and her retinue sailing by in 1844.

This is a fuller version of an article that appeared in ‘The World of Interiors’ in March 2014

The Courtyard of the Black Agas, in the Harem of Topkapı Palace, is open to the public daily except Tuesdays. The Dormitories are under restoration. For details, see topkapisarayi.gov.tr/en

Connoisseur Special

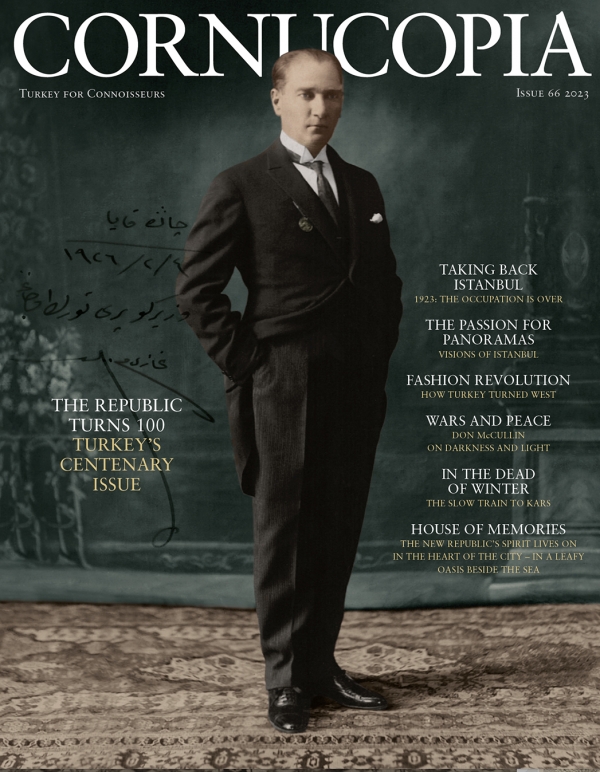

Issue 66, December 2023

Turkey’s Centenary Issue

Issue 66, December 2023

Turkey’s Centenary Issue

Bezmärä Ensemble

The Emirğan Ensemble

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now