Buy or gift a stand-alone digital subscription and get unlimited access to dozens of back issues for just £18.99 / $18.99 a year.

Please register at www.exacteditions.com/digital/cornucopia with your subscriber account number or contact subscriptions@cornucopia.net

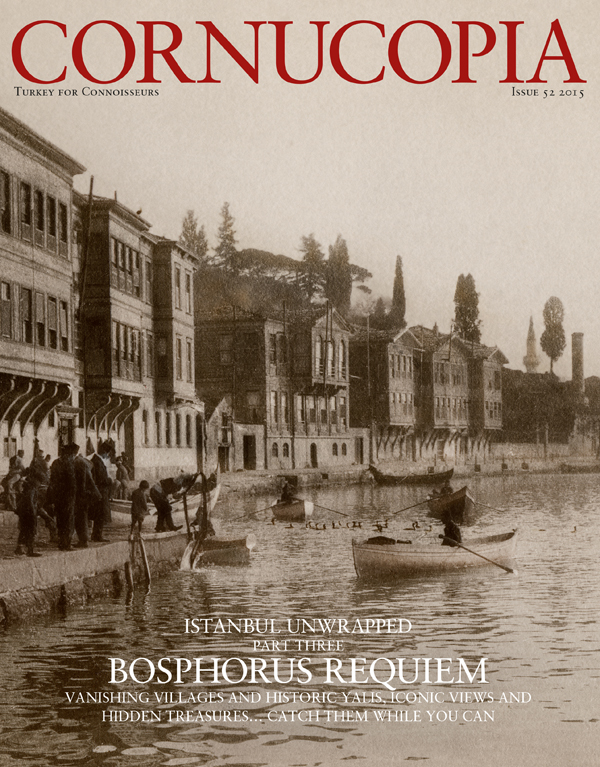

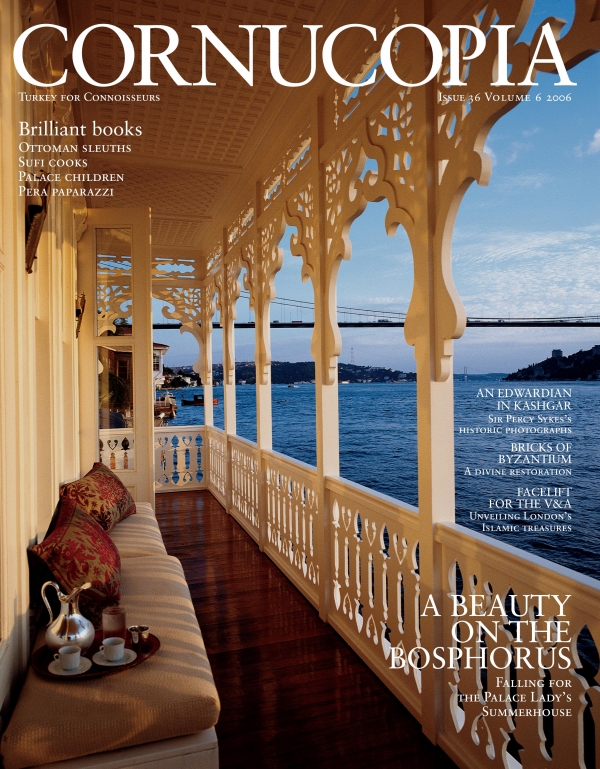

Buy a digital subscription Go to the Digital EditionAfter years of neglect, the Savfet Pasha Yalı became a much loved, if leaky home, filled with the sound of classical music. Arlette Mellaart, who went to live there at 15, recalls three happy decades spent in this fragile bohemian setting, her stepfather’s haughty mother, the cats and the rats, the bustling Bosphorus, the parties, the wartime intrigues, and married life – all to the accompaniment of her mother’s piano playing

Subscribers can read the full article, complete with illustrations, in the digital edition of Cornucopia No 25. The article was reprinted as a chapter of Alan Mellaart’s recent biographical tribute to his parents, James Mellaart: The Journey to Çatalhöyük

One morning in early June 1939, I was awoken by my grandfather violently knocking on the door of the room where my mother and stepfather were still asleep. At that time we were living in a villa in Monte Carlo. My mother had just remarried and they were leaving for Turkey that morning. Convinced that war was imminent, my grandfather said I might not be able to join them later in Istanbul if I remained with him in Monaco. So my few belongings were hastily packed and we rushed off to catch the train to Milan, then the Orient Express to Istanbul.

This is how, at the age of 15, I came to live in a very large, beautiful, ramshackle 18th-century wooden house on the Asiatic shore of the Bosphorus, not far from Istanbul.

My stepfather was descended on his father’s side from a scholar in Samarkand who, in the fourteenth century, quarrelled with Tamerlane and left for Gaziantep, in southeast Turkey. On his mother’s side, his ancestors were scholars also, as well as diplomats who served the Ottoman Empire in various capacities, from Morea to Syria and Egypt, spending most of their lives as envoys and viziers of the Sublime Porte.

When my mother and I arrived in the yalı, it was just emerging from a long period of decay. After being occupied by soldiers during the First World War, about a third of it had to be pulled down. When the Allies occupied Istanbul in 1918, a friend of the family, a kind and flamboyant Scot who proudly wore a kilt, had managed to get himself billeted there so as to prevent more destruction, this time by the victorious foreign troops. Much later, another Scotsman in a kilt was to become part of our family.

In 1918, the family fortunes were at an all-time low and the yalı of Savfet Pasha suffered for many years. In 1939, however, my mother undertook to repair and maintain it, which she did almost to the end of her life.

When we arrived, my stepfather’s mother was in residence, surrounded by about twenty cats and dogs who ate out of precious Chinese bowls scattered on the floor of her room. A haughty lady of seventy, she had the figure of a young girl and a temper to be reckoned with. Thoroughly independent at the age of thirteen, she would ride on the estate of her grandfather, the Grand Vizier Savfet Pasha, in European riding costume and without a veil. The Sultan called his minister and asked him to tell his granddaughter that she must dress in a manner appropriate to a Turkish lady, including the veil. “But she is only 13, a mere child,” was the reply.

A year later to the day, the Sultan called Savfet Pasha. “Is your granddaughter still only thirteen years old?” he asked gently. All her life Seniye Hanımefendi did exactly as she pleased, and we were made to feel that she was less than enchanted by our arrival.

The house improved day by day. It had sagged badly on one side and the local builder devised a hilarious but efficient method to shore it up: long planks were inserted under the sagging side and all the heavyweights of the village were asked to come and sit on the protruding ends, which slowly lifted the sinking side. It was then shored up with thick wooden blocks.

As we could not afford to paint the exterior, the old wood was allowed to keep its silvery-brown patina. Inside, the vast halls and well-proportioned rooms were painted cream, pale green and pale blue, with the doors and carved ceilings in contrasting colours. The waters of the Bosphorus caused luminous shadows to dapple the walls and ceilings, as the shutters were warped and the curtains too few.

The floors creaked and were not entirely flat. But there was an atmosphere of elegance and charm, enhanced by the yal›’s numerous windows overlooking the Bosphorus and the opposite shore.

True to my grandfather’s prediction, war broke out in September 1939, but he had had time to send from Monaco some beautiful furniture which put the finishing touches to the new – and last – period in the life of Savfet Pasha’s Yalı.

My mother was a musician and had three grand pianos. They arrived from Istanbul on horse-drawn carts and were carried to the first floor by tall, mustachioed men who put them on their backs and lifted them with the utmost ease, for this was their speciality. They also carried up large Renaissance chests filled with delicate crockery, without breaking a single thing…

Subscribers can read the full illustrated article in the digital edition of Cornucopia No 25

James Mellaart died 29 July 2012 aged 86

The Times obituary. Arlette Mellaart died in London in 2014.

The remarkable photography of Zafer Baran emerged from a hard-edged education in a Bauhaus atmosphere. But Baran’s powers of observation were to lead him into a world of pure colour, moods and associations into which the viewer is irresistibly drawn.

Chinese blue and white has had an unparalleled influence on taste in East and West for more than six centuries. Every self-respecting Islamic court had its collection of this precious porcelain, but the Topkapı Palace amassed one of the richest in the world.

They are a dedicated breed, but not all orchid hunters share the same agenda. Some are driven to record in minute detail the glory of Turkey’s orchid species – all 148 of them. Some are more interested in eating them. The botanist Andrew Byfield joins the quest.

Georgia’s 9,000-year love affair with the grape has produced many a spectacular wine. Here Kevin Gould continues his series on the wines of Turkey and the former dominions of the Ottoman Empire with a visit to the country that boasts 500 grape varieties. By Kevin Gould with photographs by Jason Lowe

The Crimean Church in Istanbul: a monument to Victorian Gothic. By Geofrey Tyack. Photographs by Kerem Uzel

In 1960 Maureen Freely’s family packed up all they possessed, waved goodbye to Princeton, New Jersey, and stepped out into the unknown. She had no idea why. Their destination was to her merely a name on a map: Istanbul. It was to become the place she still thinks of as home. Her father, John Freely, would write the classic guidebook ‘Strolling Through Istanbul’. More than forty years later, Maureen looks back on a golden childhood of parties, laughter and, above all, adventure

When the traveller Evliya Çelebi went to Bursa in the seventeenth century, he declared that the chestnuts there were “unrivalled in the entire world”. They are still famous today - and this is the heartland of Turkish marron glacés.

More cookery features

Cihat Aşkin, violin. Produced by Ateş Orga

The Prague Symphony Chamber Orchestra with Cihat Askin, violin. Directed by Emre Araci and produced by Ateş Orga

Cornucopia works in partnership with the digital publishing platform Exact Editions to offer individual and institutional subscribers unlimited access to a searchable archive of fascinating back issues and every newly published issue. The digital edition of Cornucopia is available cross-platform on web, iOS and Android and offers a comprehensive search function, allowing the title’s cultural content to be delved into at the touch of a button.

Digital Subscription: £18.99 / $18.99 (1 year)

Subscribe now